You are here

Science Resources: DNA Technologies

Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Services Offer Access to Genetic Data and Analyses

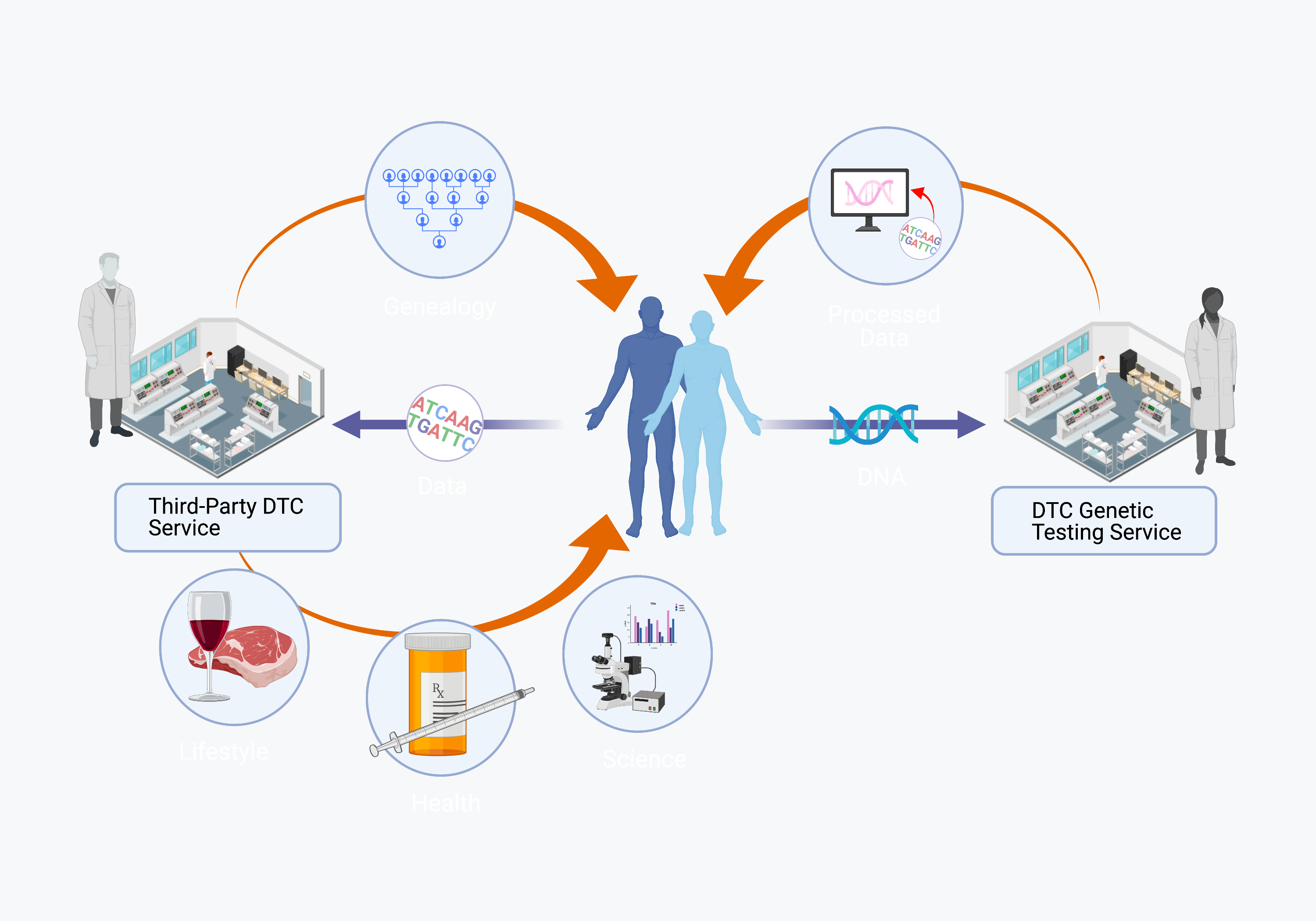

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing provides customers with insights about their ancestry, health/wellness, and behaviors by making use of easy genetic data collection and the numerous databases linking genetic and nongenetic traits.[1] In a basic DTC model, customers submit a saliva sample to the company, which performs DNA sequencing or SNP genotyping and makes the data, along with some analyses, available to the customer through its website (Fig. 15).[2]

Figure 15. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing is a complex system with data flowing from participants to testing services and numerous third-party platforms. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing services collect DNA samples from customers and return insights into their genetics along with the data itself. Customers can then upload their data to numerous third-party DTC platforms that provide an array of services, including extended genealogical searches, health/wellness information, and lifestyle information.

DTC companies have historically relied on genome-wide SNP genotyping, but some now offer whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing. DTC services may help find relatives (genetic genealogy), offer insights about geographic origins (ancestry analyses), make suggestions about lifestyle choices, or provide validated clinical tests for health conditions (Fig. 15). DTC genetic databases are also being leveraged increasingly by law enforcement to assist in identifying forensic samples.

Customers can also download their raw genetic data and retain it themselves, sharing it with their clinicians or sending it to third-party DTC platforms (Fig. 15).[3] These third-party DTC platforms do not perform any genotyping or sequencing; instead, they offer additional analyses and services. For example, third-party platforms can provide extended genealogy searches, allowing users to find relatives who may have been genotyped by a different service.

These platforms also purport to provide insight about health or lifestyle decisions, like what type of diet is best for customers or certain disease risks. The services can fall into a regulatory gray area, not technically being medical devices or diagnostic tests, and describing results as “wellness” rather than health related.[4] Combined, DTC platforms retain genetic data on tens of millions of customers.[5]

DTC genomic companies often commercialize customers’ de-identified genetic and trait data by contracting with pharmaceutical, biomedical, and genetic researchers. Customers must opt in to have their data included in research studies, but this may not always be the case. The terms of agreement are dictated by the company, and details regarding how data are managed are limited.[6]

Customers will frequently experience different protections of their data across different DTC platforms, which could cause confusion, exposure of personal information, and risk of discrimination. For example, Ancestry and 23andMe have explicitly stated that, while they will respond to any legally issued subpoena or warrant, they will challenge or seek to narrow the scope of law enforcement efforts to access or use customer data.[7]

Still, customers regularly transfer their data to third-party DTC services, where extensive legal resources and assurances are not available. And protections for the same DTC service may change during the time the customers’ data are retained in that database, without the opportunity to reconsent or remove their data. In the case of the Golden State Killer, for example, investigators uploaded data from an unknown forensic DNA sample to the third-party genealogy platform GEDmatch.[8] At the time, GEDmatch had no explicit policy regarding law enforcement searching their database, and it had not warned customers that such searches were possible.

After some initial fits and starts, GEDmatch moved to an opt-in system for existing users, where customers could choose to make their data available for law enforcement searches for a broader set of crimes. While existing users were required to opt in to law enforcement use, customers uploading new data profiles to the site are opted in by default.

In June 2019, shortly after GEDmatch introduced its law enforcement searching option, a state judge in Florida granted a warrant to investigators to access the entire GEDmatch database, regardless of whether customers had consented to the GEDmatch search policy.[9] In that specific case, however, investigators had performed a search of the GEDmatch database before users were opted out, so they sought to access DNA profiles to which they previously had access.[10]

The disjointed system of protections and the capacity for these protections to change even within a company put customers’ privacy at risk. These risks are compounded by customers’ frequent transfers of data from DTC services to the customers’ healthcare providers or the transfer from research studies to DTC platforms, where the protections provided to an individual’s genetic data can change dramatically. This can create a confusing environment where individuals unwittingly risk exposure and discrimination.

[1] Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing, MedlinePlus, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/dtcgenetictesting/ (last updated Sept. 10, 2020); Direct-to-Consumer Genomic Testing, Nat’l Hum. Genome Resch. Inst., https://www.genome.gov/dna-day/15-ways/direct-to-consumer-genomic-testing (last updated Feb. 4, 2022); Mary A. Majumder et al., Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing: Value and Risk, 72 Ann. Rev. Med. 151 (2021), available at https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-070119-114727.

[2] Antero Vanhala, & Karita Reijonsaari, Direct-To-Consumer Genome Data Services and Their Business Models (Sitra 2013), https://media.sitra.fi/2017/02/28142338/Direct_to_consumer_genome_data_services_and_their_business_models.pdf.

[3] Christi J. Guerrini et al., Who’s on Third? Regulation of Third-Party Genetic Interpretation Services, 22 Genetics in Med. 4 (2020), available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0627-6; Madjumer et al., supra note 1.

[4] Guerrini et al., supra note 3.

[5] Ringing in 23andMe’s Next Chapter, 23andMe Blog (June 17, 2021), https://blog.23andme.com/news/news-23andme-on-nasdaq-%e2%80%8e/; Autosomal DNA Testing Comparison Chart, Int’l Soc’y Genetic Genealogy Wiki (Jan. 30, 2024), https://isogg.org/wiki/Autosomal_DNA_testing_comparison_chart; Ancestry Corporate, Ancestry Surpasses 15 Million DNA Customers, Ancestry Blog (May 21, 2019), https://www.ancestry.com/corporate/blog/ancestry-surpasses-15-million-dna-customers .

[6] James W. Hazel & Christopher Slobogin, Who Knows What, And When?: A Survey of the Privacy Policies Proffered by U.S. Direct-To-Consumer Genetic Testing Companies, 28 Cornell J. L. & Pub. Pol’y, Fall 2018, at 35–66, https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1490&con....

[7] Ancestry Guide for Law Enforcement, Ancestry (n.d.), https://www.ancestry.com/cs/legal/lawenforcement; 23andMe Guide for Law Enforcement, 23andMe (n.d.), https://www.23andme.com/law-enforcement-guide/; Ancestry, Ancestry Transparency Report, July 2023, https://www.ancestry.com/cs/transparency.

[8] Laurel Wamsley, In Hunt for Golden State Killer, Investigators Uploaded His DNA to Genealogy Site, NPR (Apr. 27, 2018), https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/04/27/606624218/in-hunt-for-golden-state-killer-investigators-uploaded-his-dna-to-genealogy-site.

[9] Kashmir Hill & Heather Murphy, Your DNA Profile Is Private? A Florida Judge Just Said Otherwise, N.Y. Times: Business (Nov. 5, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/05/business/dna-database-search-warrant.html; Jocelyn Kaiser, A Judge Said Police Can Search the DNA of 1 Million Americans Without Their Consent. What’s Next?, Science: Sci. & Pol’y, (Nov. 7, 2019), available at https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba1428.

[10] Search Warrant for GEDmatch, Orlando Police Dep’t (9th Cir. June 14, 2019), https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/6547788/Orlando-PD-Search-Warrant-for-GEDMatch.pdf.