Students of early federal court history exploring the Federal Judicial Center’s history website—particularly the section on the U.S. circuit courts, the federal judiciary’s main trial courts from 1789 to 1911—might notice some anomalies. The dates for the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of New York, for example, are given as “1789–1801, 1802–1814.” The end date of 1814 is easily explained, as that was the year in which Congress divided the District of New York into the Northern and Southern Districts of New York. But confusion over what happened to that court (and to all circuit courts other than one in the District of Columbia) between 1801 and 1802 is understandable. This exhibit explains that brief and strange period in federal judicial history.

The U.S. Circuit Courts of New York, 1789–1911

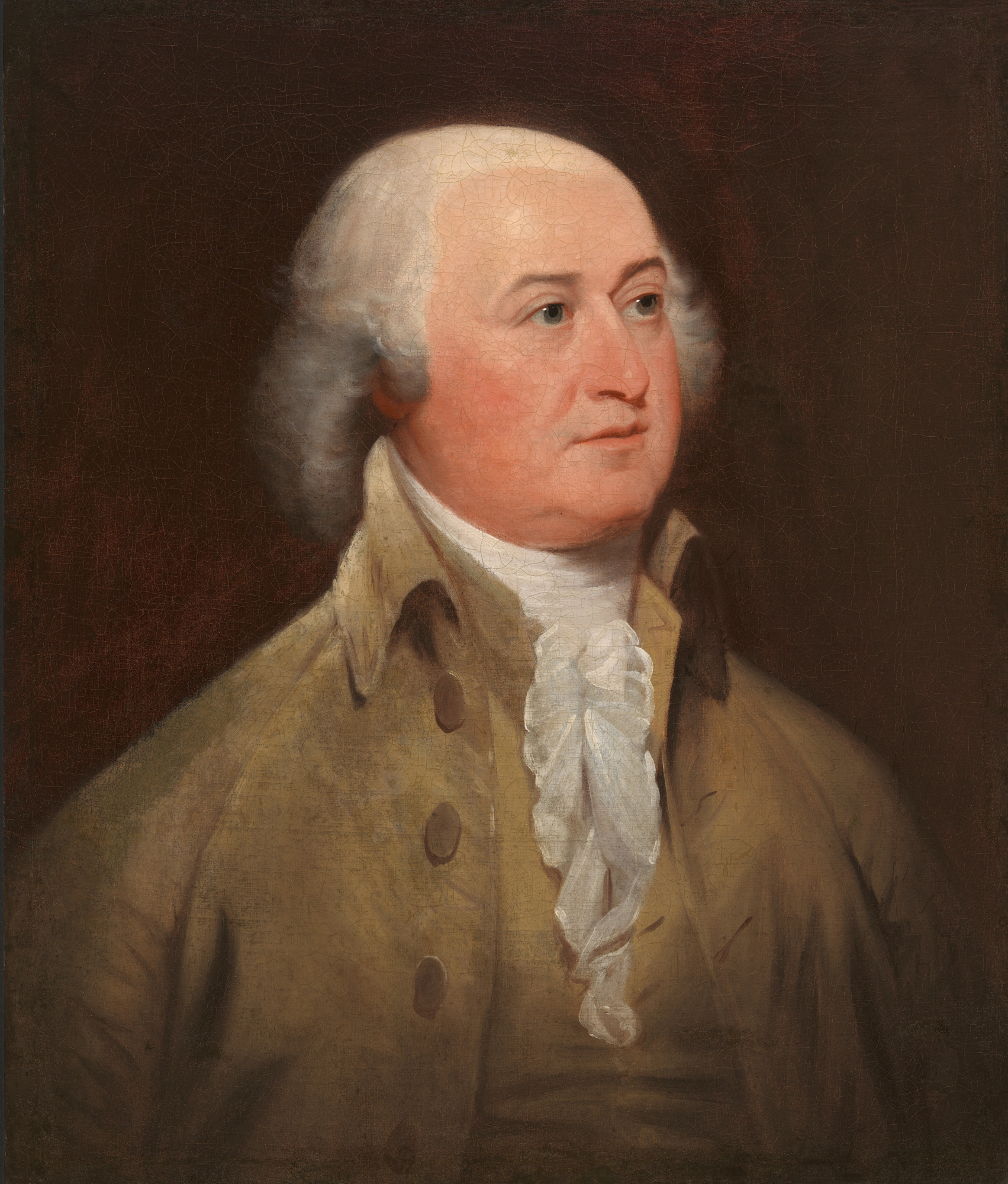

President John Adams (1797–1801) (Source: National Portrait Gallery)

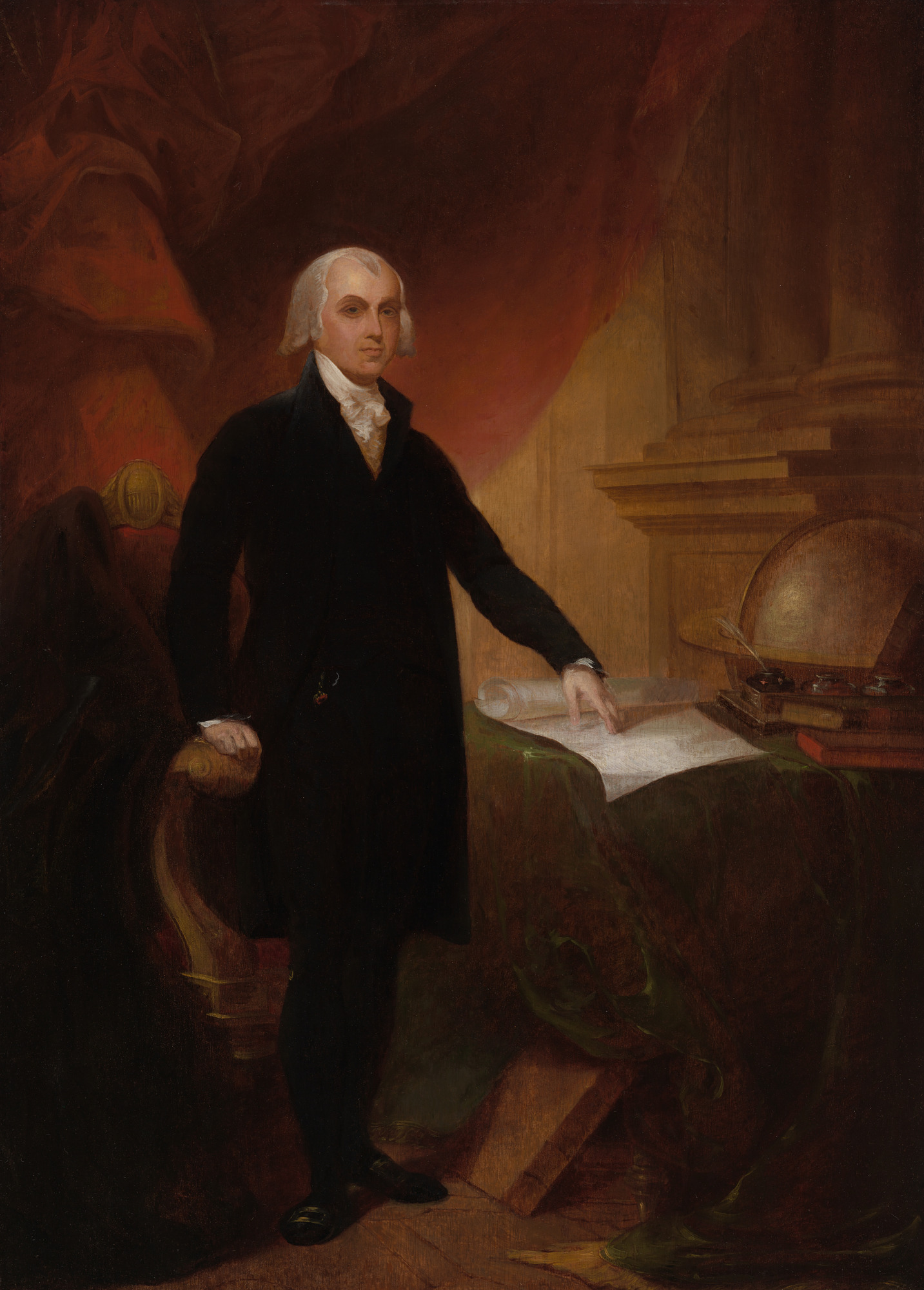

James Madison played a central role in framing the U.S. Constitution (Source: National Portrait Gallery)

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the delegates were divided as to whether the nation should have federal courts below the Supreme Court of the United States. Some delegates felt that the state courts were sufficient to handle all the nation’s judicial business. They feared that federal courts would make the national government too powerful and would eventually dominate to an extent that would render the state courts irrelevant. Those in favor of federal courts believed them to be necessary for the effective enforcement of federal law. The so-called Madisonian Compromise, embodied in Article III of the Constitution, provided that the Constitution would create no inferior federal courts but would instead allow Congress to decide what courts, if any, to establish.

In the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress divided the nation into thirteen judicial districts, eleven of which were assigned to the Eastern, Middle, and Southern Circuits (North Carolina and Rhode Island were not yet included because they had not ratified the Constitution; Kentucky and Maine, comprising judicial districts but still parts of other states, were not assigned to circuits). The Act established the U.S. circuit courts as the primary trial courts and the U.S. district courts to hear admiralty and maritime cases and some minor civil and criminal matters. The circuit courts lacked their own judges; they were held instead by the justices of the Supreme Court riding circuit and the district judge for each judicial district. Although it created an extensive network of federal courts, the Act did not establish a dominant national judiciary. While Article III extended the federal judicial power to all cases arising under federal law, Congress did not grant the lower federal courts such jurisdiction in the 1789 Act, leaving state courts to handle most federal law issues.

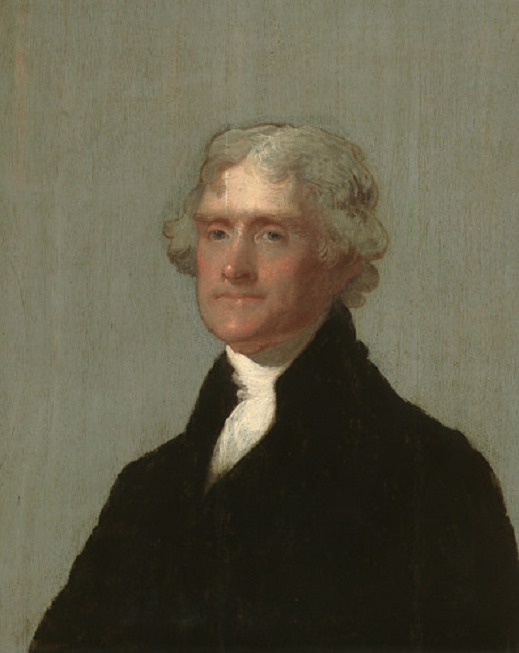

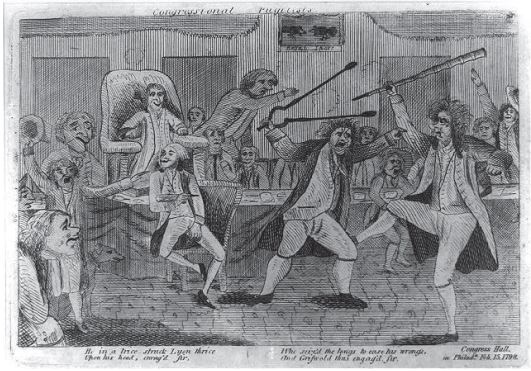

In the early years of the republic, a division occurred between two newly formed political coalitions. The Federalists, who supported the administrations of George Washington and John Adams, favored a strong national government, while the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, preferred most governing to be done at the state level. Differences between Federalists and Jeffersonian Republicans extended to their views on the judiciary. Federalists wanted to give federal courts increased authority to protect the federal government from interference by hostile state governments. Republicans, in the Anti-Federalist tradition, were wary of centralized authority and believed that most judicial power should remain vested in the state courts. While these coalitions lacked the formal structure of later political parties, competition between them intensified during the late 1790s, reaching a fever pitch when several Republican opponents of the Adams administration were prosecuted under the Sedition Act of 1798 for allegedly disloyal behavior.

President Thomas Jefferson (1801–1809) (Source: National Portrait Gallery)

A satirical print depicting the notorious brawl on the floor of the House of Representatives between Republican Matthew Lyon and Federalist Roger Griswold in 1797 (Source: Library of Congress)

The Republicans soundly defeated the Federalists in the bitterly contested election of 1800, and for the first time, political power in the young republic was due to change hands from one party to another. Federalists, viewing the Republicans as disloyal and seditious, feared Thomas Jefferson’s ascension to the presidency with a new Republican majority in Congress. The Federalists’ apprehension of what was soon to come had implications for the federal judiciary. At the time of the election, Congress was already debating federal court reform. Much of the impetus for change came from complaints about the circuit-riding system provided for in 1789, with the loudest complaints coming from the justices themselves. The justices felt burdened by the rigors of extensive travel and had misgivings about sitting as trial judges on cases they might later hear on appeal, an arrangement that could impair public confidence in the judiciary. In 1793, Congress had eased the justices’ burden somewhat by reducing the number of them required to attend each circuit court session from two to one, but circuit riding remained onerous.

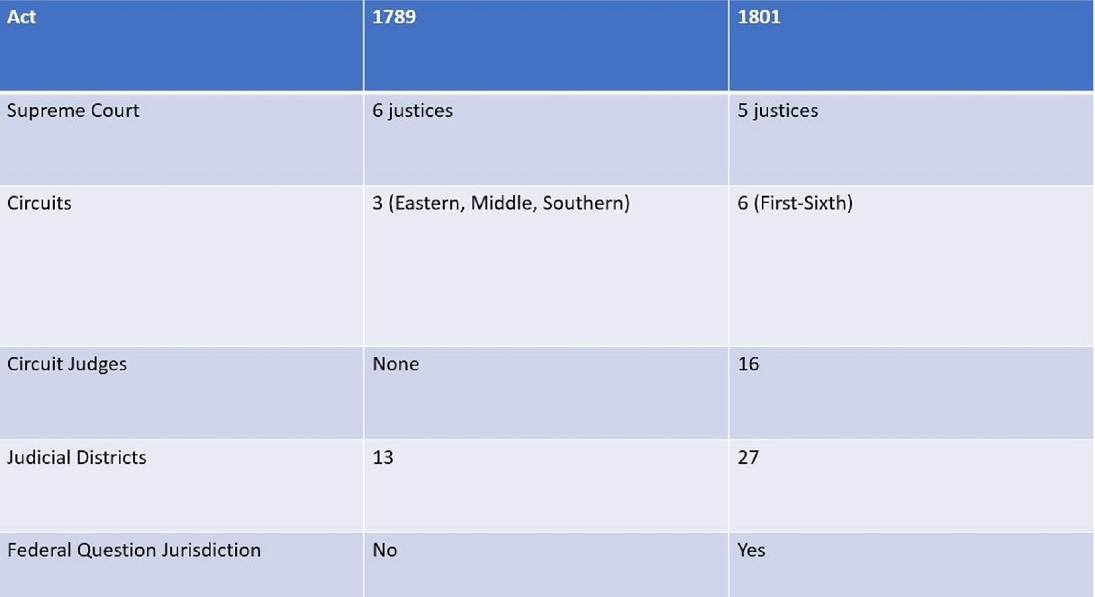

In the closing days of the lame-duck Adams administration, the outgoing Federalist majority in Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1801. The Act reduced the size of the Supreme Court from six justices to five and abolished the Eastern, Middle, and Southern Circuits, replacing them with six numbered circuits. The circuit courts for each judicial district were abolished as well, to be replaced by a regional circuit court (with multiple meeting places) for each circuit. The circuit court that met in Boston, for example, would no longer be a circuit court for the District of Massachusetts but a circuit court for the First Circuit. The Act also created sixteen circuit court judgeships. The First through Fifth Circuits would each have three circuit judges, while the Sixth Circuit would be held by one circuit judge and the district judges for Kentucky and Tennessee (whose district courts the Act abolished). The creation of dedicated circuit court judgeships eliminated the justices’ circuit-riding duties and relieved the district judges of their circuit court obligations as well.

The first section of the Judiciary Act of 1801 (Source: HeinOnline)

The Judicial Circuits Before and After the Judiciary Act of 1801

(Source: Federal Judicial Center)

(Source: Federal Judicial Center)

The Judiciary Act of 1801 also made a significant change to federal court jurisdiction, bolstering the Federalists’ effort to create more powerful federal courts with an expanded judicial role. Section 11 of the Act provided the circuit courts with jurisdiction over all cases arising under the Constitution, laws of the United States, and treaties, thereby stretching the federal courts’ jurisdiction to the limits set by Article III. The division of several judicial districts to establish more circuit and district court locations would bring federal courts closer to the people and increase their prominence relative to state courts, further enhancing federal judicial power.

Comparison of key provisions in the Judiciary Acts of 1789 and 1801 (Source: Federal Judicial Center)

U.S. Circuit Court Meeting Places Before and After the Judiciary Act of 1801

(Source: Federal Judicial Center)

(Source: Federal Judicial Center)

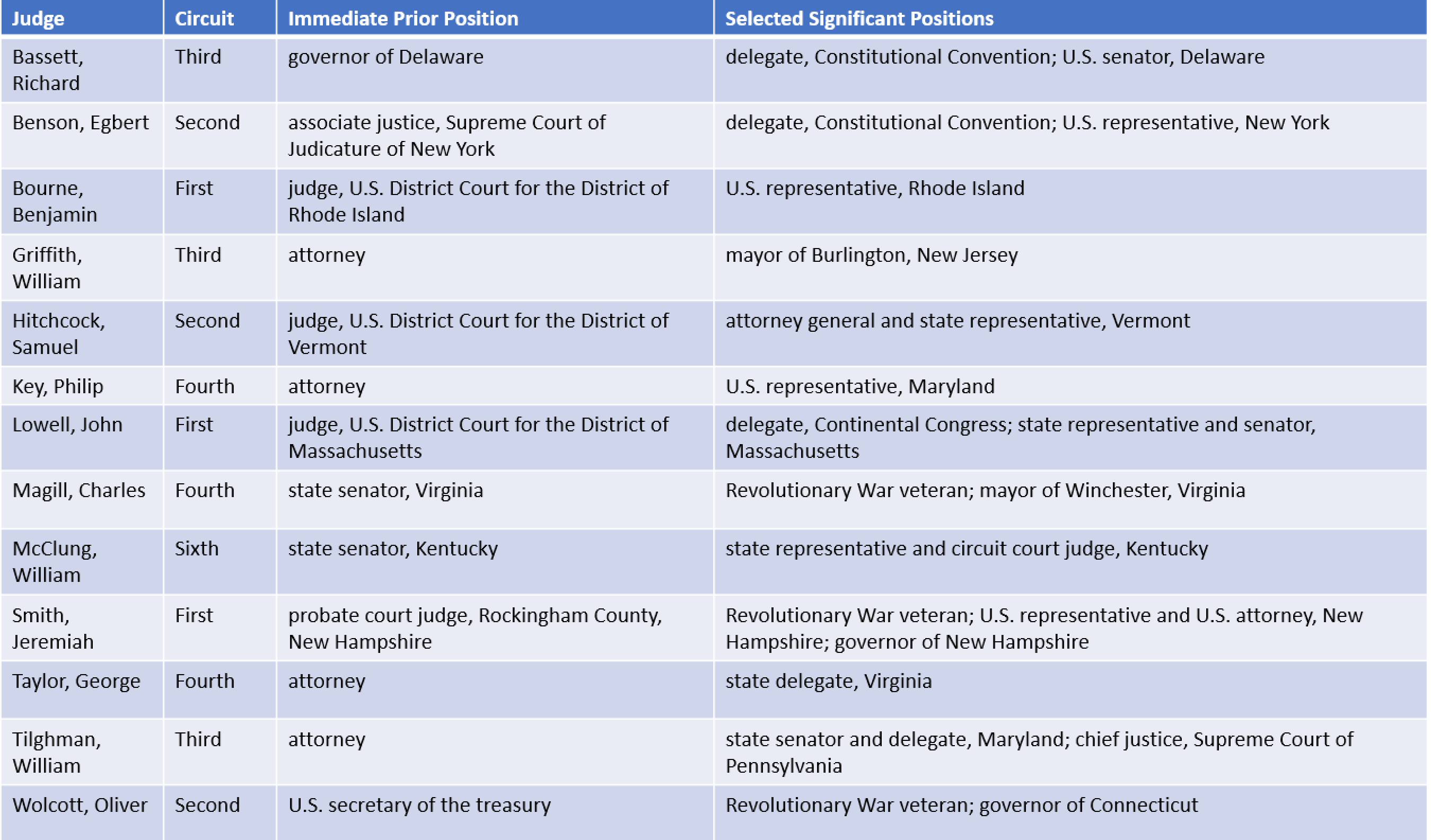

Republicans were strongly opposed to the 1801 Act, particularly because the Federalists enacted it during a lame-duck period following a decisive electoral defeat. In Republicans’ view, the new circuit judgeships were a Federalist ploy to pack the federal courts with political allies. As a result, the circuit judges Adams appointed just before leaving office came to be known as the “midnight judges,” a pejorative term reflecting the last-minute nature of their appointments and casting doubt on their legitimacy. Republicans also saw the Federalists’ bolstering of federal judicial power as a way to weaken the elected branches of government just as the Republicans were poised to assume control. The controversial prosecutions of Republicans under the Sedition Act of 1798 made them especially wary of strong federal courts staffed by Federalist judges.

Clockwise from top left: “Midnight Judges” Egbert Benson, Samuel Hitchcock, John Lowell, and Benjamin Bourne (Source: Wikipedia)

Judges of the First Through Sixth Circuits, 1801–1802

(Source: Federal Judicial Center)

Clockwise from top left: Judges Richard Bassett, William Tilghman, Oliver Wolcott, Henry Potter, Jeremiah Smith, and Dominic Hall (Sources: National Portrait Gallery (Bassett), Wikipedia (all others))

- Marbury v. Madison (click to learn more)

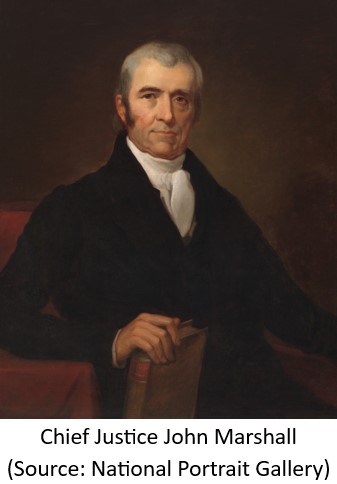

Legislation enacted by the lame-duck Federalists, combined with the transfer of power to the Jeffersonians, produced the landmark Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison (1803). In a statute separate from the Judiciary Act of 1801, Congress created new judicial positions for the District of Columbia, including three circuit court judgeships and any number of justices of the peace the president chose to appoint. Among the justices of the peace Adams appointed was William Marbury, whom the Senate confirmed on the last day of Adams’ presidency. Adams signed Marbury’s commission, but it was not delivered to Marbury before Adams left office. It was Marbury’s suit asking the Supreme Court to compel Secretary of State James Madison to deliver his commission that produced Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion holding that federal courts have the power to strike down federal laws that violate the Constitution. (A provision of the 1801 Act, which allowed the Supreme Court to issue writs of mandamus to federal officials, was deemed invalid because it expanded the Court’s original jurisdiction beyond the limits set forth in Article III.)

Legislation enacted by the lame-duck Federalists, combined with the transfer of power to the Jeffersonians, produced the landmark Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison (1803). In a statute separate from the Judiciary Act of 1801, Congress created new judicial positions for the District of Columbia, including three circuit court judgeships and any number of justices of the peace the president chose to appoint. Among the justices of the peace Adams appointed was William Marbury, whom the Senate confirmed on the last day of Adams’ presidency. Adams signed Marbury’s commission, but it was not delivered to Marbury before Adams left office. It was Marbury’s suit asking the Supreme Court to compel Secretary of State James Madison to deliver his commission that produced Chief Justice John Marshall’s opinion holding that federal courts have the power to strike down federal laws that violate the Constitution. (A provision of the 1801 Act, which allowed the Supreme Court to issue writs of mandamus to federal officials, was deemed invalid because it expanded the Court’s original jurisdiction beyond the limits set forth in Article III.)

Data from Thomas Jefferson’s 1801 caseload report to Congress. The report was superseded and corrected by a new version submitted in February 1802. (Source: HeinOnline)

Soon after taking office, President Jefferson turned his thoughts to the possible repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801. When Congress convened in December 1801, Jefferson delivered his annual message on the state of the union, remarking, “The Judiciary system of the United States, and especially that portion of it recently erected, will, of course, present itself to the contemplation of Congress.” Jefferson presented Congress with a federal caseload study he had ordered to be compiled so that Congress could determine whether the circuit judgeships added in 1801 were truly needed.

In January 1802, Senator John Breckinridge of Kentucky introduced a motion to repeal the 1801 Act, and Congress embarked on a lengthy debate. Republicans argued that the federal courts did not hear enough cases to justify sixteen additional judgeships and asserted that Congress’s power to establish federal courts necessarily included the power to abolish them. Consistent with their general preference for decentralization, they also argued that circuit riding should be reestablished so that Supreme Court justices would remain familiar with the laws of different states and maintain a connection with the American people. Federalists argued that a repeal of the 1801 Act that included displacing the circuit judges would be unconstitutional because it would conflict with Article III’s guarantee of tenure during good behavior for federal judges. The Federalists also believed that the abolition of courts and judicial offices would be an abuse of power by the elected branches and would destroy the independence of the judiciary. Moreover, they felt that a return to the grueling task of circuit riding would dissuade older and more experienced judges from wanting to serve on the Supreme Court.

Senator John Breckinridge and his motion for repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 (Sources: William & Mary Law Library (Breckinridge), HeinOnline (motion))

Excerpt of congressional debate over repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 and the first two sections of the Repeal Act of 1802 (Source: HeinOnline)

With the Republicans in the majority, Congress passed the repeal act on March 8, 1802, approximately thirteen months after the 1801 Act became law, restoring the organization of the federal courts that existed prior to 1801. In April, Congress followed up with the Judiciary Act of 1802, which eliminated the Supreme Court’s next term—to prevent the Court from ruling on the constitutionality of the repeal, some alleged—and assigned the justices to ride the circuits again. In private letters, the justices discussed among themselves whether circuit riding, which placed them on courts to which they had not been appointed, was unconstitutional. But ultimately, the Court accepted the majority’s view that the practice should continue.

Excerpts of columns in the Alexandria (Va.) Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer regarding repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 (Source: Library of Congress)

The judges who were removed from office by the repeal of the 1801 Act petitioned Congress to be assigned to new judicial duties and paid their salaries, but Congress took no action on their request. Legal challenges to the constitutionality of the repeal ended with the Supreme Court’s decision in Stuart v. Laird (1803), in which the Court held that Congress had the authority to transfer a case from a court established under the 1801 Act to a court created under the 1802 Act.

Justice William Paterson (1793–1806) delivered the Supreme Court's opinion in Stuart v. Laird (1803) (Sources: Oyez (Patterson), HeinOnline (opinion))

- The Impeachment of Samuel Chase (click to learn more)

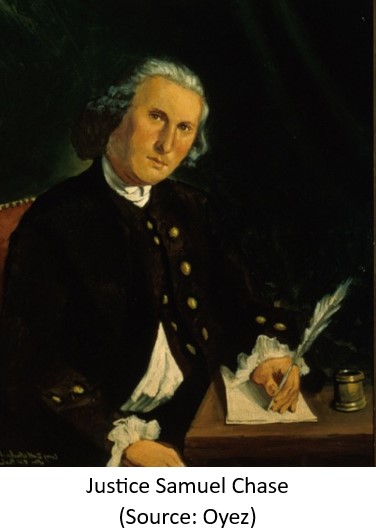

Congress’s repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 led indirectly to the only impeachment of a Supreme Court justice. Justice Samuel Chase was an ardent Federalist supporter who had campaigned openly for John Adams in the 1800 presidential election. In 1803, Justice Chase gave a grand jury charge while riding circuit in Maryland. While justices’ grand jury charges were frequently wide-ranging and included commentary on matters of public concern in addition to the law, Chase’s remarks were unusually partisan. He was strongly critical of the Republicans for repealing the 1801 Act and abolishing the circuit judgeships, accusing them of undermining the independence of the federal judiciary. The charge became controversial and was the catalyst for the House of Representatives to impeach Chase. The House presented eight articles of impeachment, one of which focused on the allegedly seditious nature of the grand jury charge. Most of the other articles arose from Chase’s allegedly improper behavior during politically charged trials such as the Sedition Act prosecutions. Chase argued that only indictable offenses constituted the “high crimes and misdemeanors” for which he could be removed from office. He was acquitted by the Senate.

Congress’s repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 led indirectly to the only impeachment of a Supreme Court justice. Justice Samuel Chase was an ardent Federalist supporter who had campaigned openly for John Adams in the 1800 presidential election. In 1803, Justice Chase gave a grand jury charge while riding circuit in Maryland. While justices’ grand jury charges were frequently wide-ranging and included commentary on matters of public concern in addition to the law, Chase’s remarks were unusually partisan. He was strongly critical of the Republicans for repealing the 1801 Act and abolishing the circuit judgeships, accusing them of undermining the independence of the federal judiciary. The charge became controversial and was the catalyst for the House of Representatives to impeach Chase. The House presented eight articles of impeachment, one of which focused on the allegedly seditious nature of the grand jury charge. Most of the other articles arose from Chase’s allegedly improper behavior during politically charged trials such as the Sedition Act prosecutions. Chase argued that only indictable offenses constituted the “high crimes and misdemeanors” for which he could be removed from office. He was acquitted by the Senate.

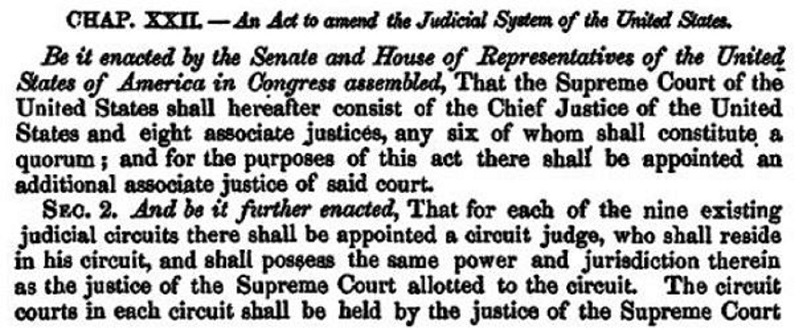

The first two sections of the Circuit Judges Act of 1869 (Source: HeinOnline)

While the Federalists’ judicial innovations of 1801 were dismantled almost immediately, important elements of those short-lived reforms appeared decades later. The Circuit Judges Act of 1869 was motivated by the federal courts’ increased workload in the wake of the Civil War. The Act restored the number of seats on the Supreme Court to nine (it had recently been reduced to seven) and created a new tier of federal judgeships, providing a circuit judge for each of the then-nine circuits. A circuit court could be held by a justice, a circuit judge, a district judge, or any two of them together, making possible the simultaneous meeting of multiple courts within a circuit and reducing the burdens of circuit riding. The Jurisdiction and Removal Act of 1875 granted the federal courts jurisdiction over cases arising under the Constitution, federal laws, and treaties, thereby expanding the courts’ jurisdiction to the limits set forth in Article III for the first time since 1801. The 1875 Act also expanded the right to remove a case from state to federal court. While this measure helped to protect freed people from prejudice in Southern state courts, it was also aimed at preventing state courts from hindering large business interests.

The history of the Judiciary Act of 1801 reflects the intense partisanship of the late 1790s and early 1800s, differing philosophies about the federal courts, and important debates about judicial independence. While the Act may have been passed under the wrong circumstances at the wrong political moment, its legacy lived on, manifesting in later judicial reforms. The Federalists were short-lived as a political party, but their vision of a strong national judiciary eventually won out over the Jeffersonian Republicans’ preference for a system in which state courts predominated.