From 1920 until 1933, the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages was banned in the United States under the policy known as Prohibition, enshrined in the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. While some states had already gone dry, Prohibition on the national level represented a huge victory for the American temperance movement that had existed for a century. The policy represented a massive expansion of federal power, as the government made the most extensive effort in its history to regulate the daily habits and lifestyles of the American people.

Prohibition produced myriad effects. It strained law enforcement resources at the federal, state, and local levels. It spawned an explosion of official corruption. It turned millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens into criminals virtually overnight. It spurred a rise in organized crime and the deadly gang violence that came with it. And it overwhelmed the federal judicial system, which was ill-equipped to handle the deluge of cases that flooded the courts. After thirteen years, the difficulties of enforcement, the rampant corruption, the widespread disrespect for the law, and the economic strain brought about by the Great Depression combined to put an end to the Prohibition era. This timeline tells the story of Prohibition with a particular emphasis on the federal courts—a topic that is largely omitted from many popular histories of the subject.

April 6, 1917: World War I

The United States enters World War I. The war gives a significant boost to the American temperance movement through the need to conserve grain for troops and allies, the belief that alcohol will harm the war effort by contributing to waste and inefficiency, and hostility toward German-Americans, who are strongly associated with the American beer industry. Furthermore, the war contributes to the expansion of the federal government's powers and the growth of the administrative state, circumstances conducive to the enactment of a national alcohol ban. Almost immediately, the federal government establishes a series of wartime prohibition measures aimed at conserving manpower and resources.

Members of an American machine gun battalion in France, 1918 (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

- Wartime Prohibition Measures (click to learn more)

-

In the standard historical narrative, national Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, the date the Eighteenth Amendment and its enforcement vehicle, the National Prohibition Act, or Volstead Act, became effective. The start of constitutional Prohibition, however, did not bring about as dramatic a change in national habits as some believe. Well before that date, the federal government had used its war powers to promulgate extensive alcohol regulations during World War I.

The first restrictions came via the Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, which made it "unlawful to sell any intoxicating liquor, including beer, ale, or wine, to any officer or member of the military forces while in uniform." For purposes of this Act, the War Department considered beverages containing at least 1.4% alcohol to be intoxicating, a provision less strict than the 0.5% standard imposed by later legislation. Additionally, as authorized by the act, the armed forces began in the spring of 1918 to set up "dry zones" within a five-mile radius of military camps where alcohol could not be sold.

A few months later, on August 10, 1917, the Food and Fuel Control Act (or Lever Act), prohibited the use of "food, fruits, food materials, or feeds . . . in the production of distilled spirits for beverage purposes." The Act also authorized the president "to commandeer any or all distilled spirits" deemed necessary for production of war supplies.

Between December 1917 and March 1919, President Woodrow Wilson used his expanded wartime presidential powers to issue three alcohol-related proclamations. The first prohibited the brewing of malt liquor, except ale and porter, containing more than 2.75% alcohol. Wilson later extended the provision to all malt beverages, whether or not they contained alcohol, and finally limited the ban to "intoxicating malt liquors."

The most significant war-related liquor law was the Wartime Prohibition Act. Despite the fact that it did not become law until November 21, 1918—ten days after the armistice that ended fighting in Europe—the Act's stated purpose was "conserving the man power of the Nation, and [increasing] efficiency in the production of arms, munitions, ships, food, and clothing for the Army and Navy." The Act provided that, beginning on June 30, 1919, until the end of the war and completion of demobilization (as determined by the president), selling distilled spirts, beer, wine, "or other intoxicating malt or vinous liquor" for beverage purposes (other than for export) would be illegal and that no food products could be used to make intoxicating beverages.

When the Wartime Prohibition Act went into effect in the summer of 1919, the fighting had been over for more than six months and the Treaty of Versailles had just been signed (though not by the United States, as the Senate had rejected it). In consequence, many believed the Act was no longer necessary. Nevertheless, the Volstead Act passed by Congress in October 1919 kept wartime prohibition in force and added measures for its enforcement. Wilson vetoed the Volstead Act on the grounds that the emergency had passed and wartime prohibition was no longer needed. Congress overrode his veto.

The Wartime Prohibition Act generated litigation from sellers of alcohol who claimed that because the war was over the Act was no longer in effect and could not be enforced. In Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries, decided in December 1919, the Supreme Court held that the conditions for terminating the Act did not yet exist. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Louis Brandeis pointed out that the United States had not signed a peace treaty, the federal government was still exercising its war powers to control the nation's railroads, "other war activities" had not concluded, and "it can not even be said that the man power of the nation has been restored to a peace footing." Although President Wilson had referred specifically to the "demobilization of the army and navy" in his message vetoing the Volstead Act, Justice Brandeis deemed the president to have used those words "in a popular sense." If Wilson considered demobilization formally concluded, Brandeis asserted, he would have issued a proclamation to that effect.

In January 1920, the Court decided Ruppert v. Caffey, which was a challenge to the wartime prohibition provisions of the Volstead Act. Unlike the original Wartime Prohibition Act, which courts had interpreted to prohibit only intoxicating beverages, Title I of the Volstead Act applied wartime prohibition to any beverage containing 0.5% alcohol or above. The plaintiff, a maker of non-intoxicating beer, argued first that wartime prohibition had expired, and second that even at the height of its war powers, Congress did not have the authority to ban non-intoxicating beverages. The Court rejected both contentions by a 5–4 vote. In another opinion by Justice Brandeis, the majority held that, for the reasons given in Hamilton, wartime prohibition had not expired. As for the scope of congressional power, Brandeis wrote, it was immaterial whether or not the plaintiff’s beer was intoxicating. The Court would not second-guess the judgment of Congress that a ban on intoxicating beverages must include any containing alcohol, if enforcement was to be effective.

Justice James McReynolds filed a dissenting opinion in which Justices William R. Day and Willis Van Devanter joined. (Justice John H. Clarke dissented separately, without issuing or joining in a written opinion.) The Court's conservatives believed that the scope of congressional power during wartime should depend on "actual necessities consequent upon war." The question as they saw it was whether, on the date the Volstead Act became law, a ban on non-intoxicating beverages "could afford any direct and appreciable aid in respect of the war declared against Germany and Austria." Reviewing the circumstances, Justice McReynolds pointed out that by the time the Volstead Act was passed, the military forces had returned home, demobilization had been completed, the production of war materiel had ceased, and much of what remained had been sold. He also quoted several statements by President Wilson to the effect that the war was over. As a result, McReynolds could see "no reasonable relationship" between the war and the banning of the plaintiff's product.

The United States remained at war, technically speaking, for a year and a half after the Volstead Act went into effect. On May 27, 1920, Wilson vetoed a congressional resolution that would have formally ended the war by declaring a state of peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary. With the U.S. Senate having rejected the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson opposed making peace without demanding any action from Germany to repair the wrongs it had committed. Not until President Warren G. Harding signed the Knox-Porter Resolution on July 2, 1921, would U.S. participation in World War I formally end.

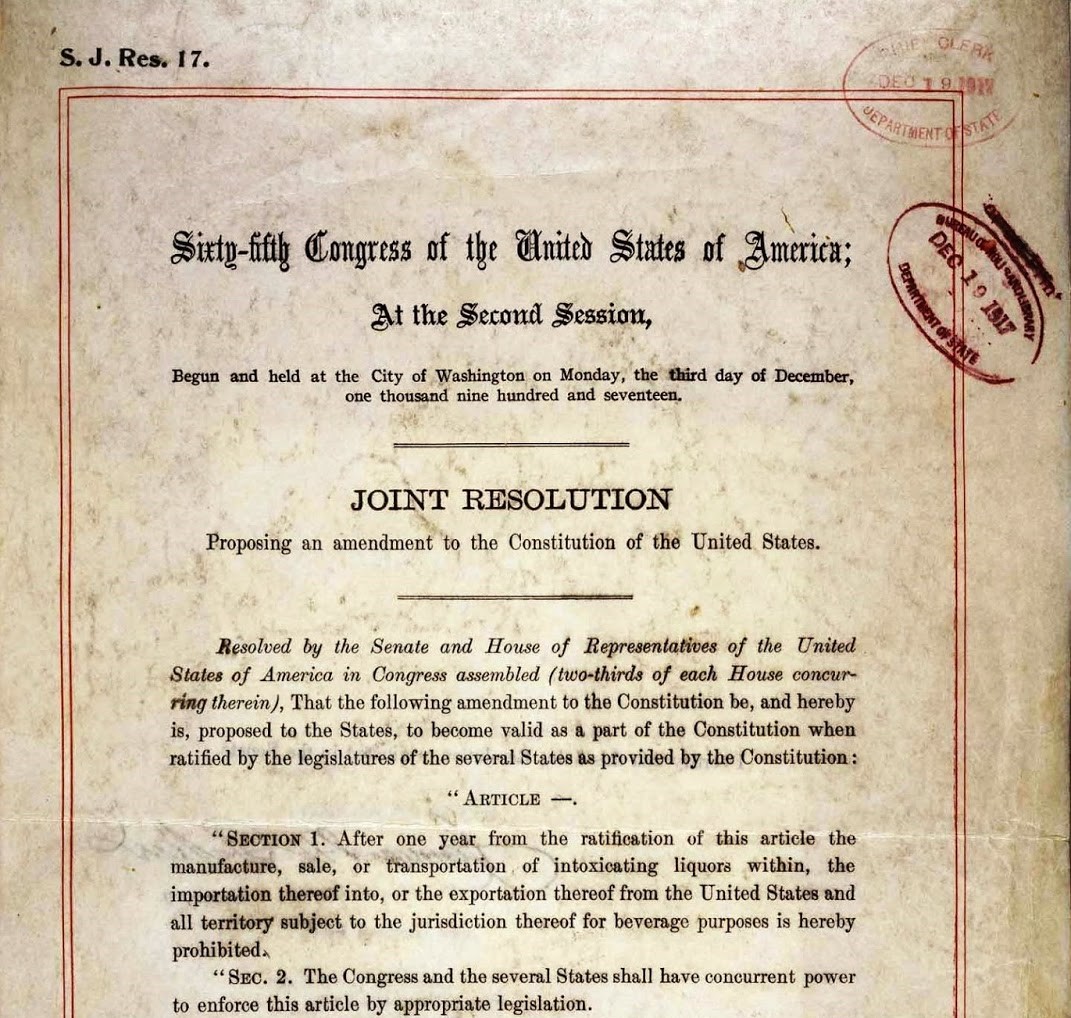

December 22, 1917: Eighteenth Amendment

Congress passes the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and submits it to the states for ratification. The amendment provides that, as of one year from ratification, "the manufacture, sale or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited." The amendment also gives the federal and state governments "concurrent power" to enforce Prohibition by appropriate legislation, an ambiguous turn of phrase that gives rise to disputes over its meaning. While Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover and other federal officials argue throughout the 1920s that the amendment puts an affirmative obligation on the states to enforce Prohibition, the Supreme Court has already implicitly rejected this interpretation in United States v. Lanza (1922). The failure of some states to enforce Prohibition vigorously puts a heavier burden on federal law enforcement officials and the federal courts.

The Eighteenth Amendment (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

January 16, 1919: Ratification

Nebraska becomes the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment, giving the amendment the approval of the necessary three-fourths of the states and completing the fastest ratification process in American history to this point. Eventually, forty-six out of forty-eight states—all but Connecticut and Rhode Island—ratify the Eighteenth Amendment.

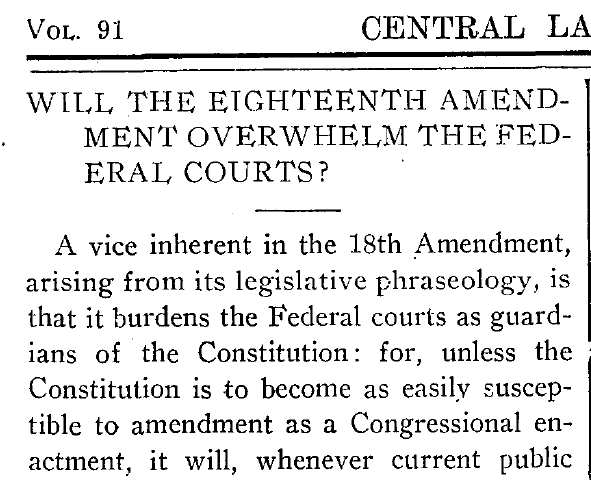

A 1920 article in Central Law Journal, published in St. Louis, Missouri, expresses concern about the Eighteenth Amendment's effect on the courts (Source: HeinOnline)

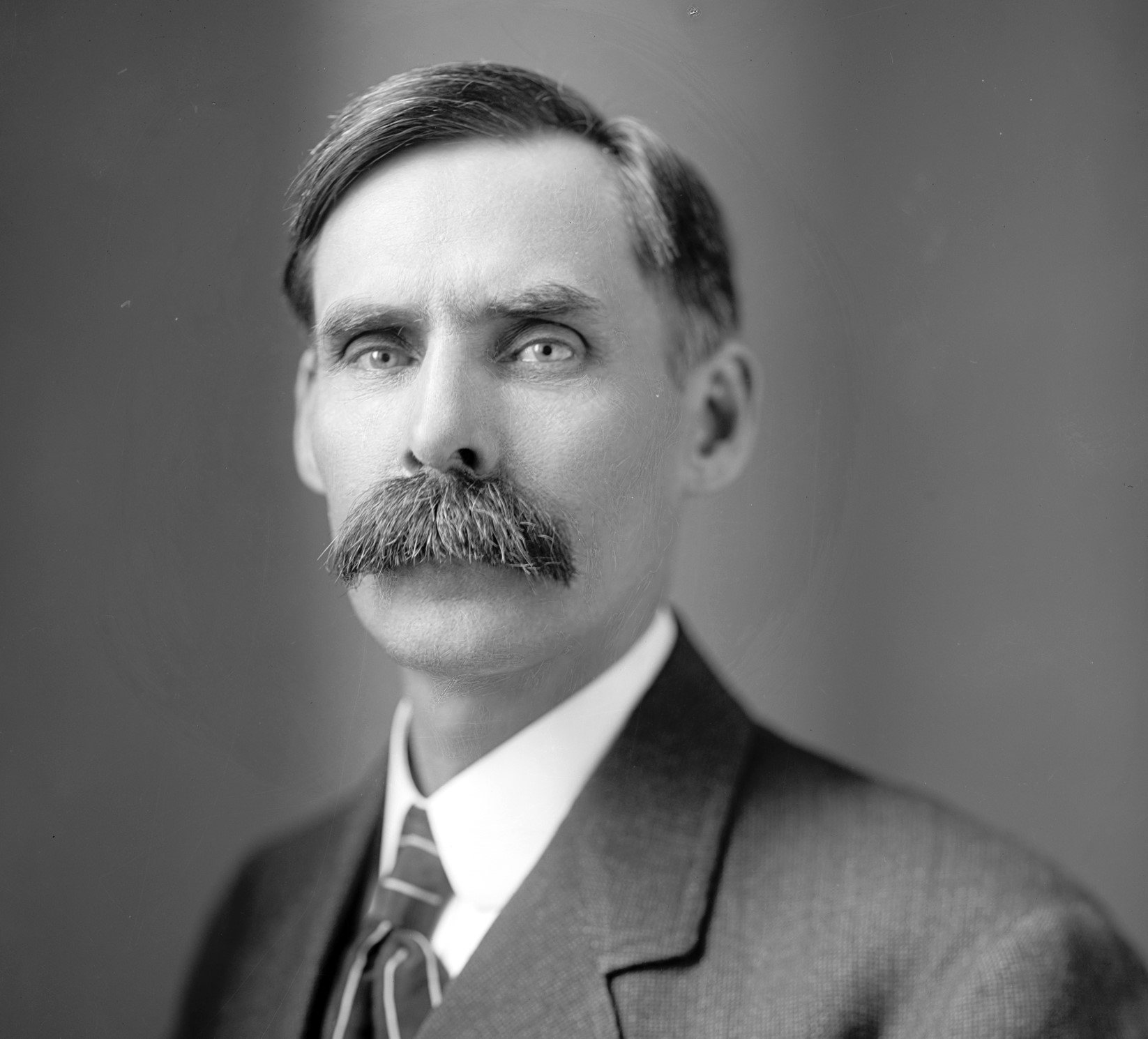

October 28, 1919: Volstead Act

The National Prohibition Act (or Volstead Act), Congress’s vehicle for enforcing the Eighteenth Amendment, becomes law over the veto of President Woodrow Wilson, who objects to the Act's inclusion of wartime prohibition provisions he believes are no longer necessary. The Act prohibits any person to "manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish or possess any intoxicating liquor," except for the limited purposes described therein. The Act defines "intoxicating beverages" as those containing more than 0.5% alcohol and provides that its terms "shall be liberally construed to the end that the use of intoxicating liquor as a beverage may be prevented." While the Volstead Act gives state and federal courts concurrent jurisdiction over suits to enjoin banned activities, it gives the federal courts exclusive jurisdiction under criminal prosecutions brought under the Act.

U.S. Representative Andrew J. Volstead of Minnesota, who introduced the National Prohibition Act to Congress (Source: Library of Congress)

January 17, 1920: Prohibition Takes Effect

The Volstead Act goes into effect. Before the clock strikes midnight on January 16, mock funerals for "John Barleycorn" (a personification of alcoholic beverages made from barley, originating in a centuries-old English and Scottish folk song) are held in cities across the nation. With wartime Prohibition restrictions still in effect, there is little public drinking in most locales, although police turn a blind eye in some cities. Because of a provision of the Volstead Act permitting the keeping in private homes of all liquor owned before the Act goes into effect, those who can afford to do so have stocked up, and the final legal deliveries of liquor take place throughout the day.

Prohibition agents destroy a bar (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

June 7, 1920: National Prohibition Cases

The Supreme Court rejects a challenge to the constitutionality of the Eighteenth Amendment in the National Prohibition Cases. Among the claims raised in suits brought by both states and private parties is that national Prohibition invades the sovereignty of the states by infringing on their traditional police powers. In a brief opinion, the Court holds that Congress acted within the bounds of the amendment power provided by Article V of the Constitution and that the consent of state governments is not required for national application of the Volstead Act.

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice William H. Taft, center, who led the Court from 1921 to 1930 (Source: Library of Congress)

- National Prohibition Cases (click to learn more)

-

Prohibition, which entailed federal regulation in an area traditionally left to the states, quickly resulted in an unusual attempt to contest the constitutionality of a constitutional amendment. At the dawn of Prohibition, the states of New Jersey and Rhode Island and private parties in several other states sued federal officials for an injunction against the enforcement of the Eighteenth Amendment. Seven separate lawsuits were consolidated for argument before the Supreme Court under the name National Prohibition Cases (1920). The plaintiffs asserted that the amendment invaded the sovereignty of the states by intruding on their traditional police powers, adding that federal enforcement regarding alcohol was anti-democratic because people expected their daily habits of life to be regulated not by a distant federal government but instead by state and local officials with whom they were more familiar. The plaintiffs also claimed that the amendment's grant of "concurrent" enforcement power meant that the federal and state governments must act jointly; in other words, federal Prohibition legislation such as the Volstead Act could not operate within a state without that state's consent.

In a brief opinion, the Court found the Eighteenth Amendment valid, holding that it had been properly executed and was within the amending power provided by Article V of the Constitution. The Court also rejected the plaintiffs' contention that the federal and state governments exercised their Prohibition powers in separate spheres, with each being supreme within its respective sphere, such that states could refuse to be bound by federal Prohibition legislation. Perhaps finding it premature or unnecessary to the resolution of the case to give a precise definition to the term "concurrent power," the Court explained what the phrase did not mean. "The words ‘concurrent power,'" wrote Justice Willis Van Devanter for the majority, "do not mean joint power or require that legislation . . . by Congress, to be effective, shall be approved or sanctioned by the several States or any of them; nor do they mean that the power to enforce is divided between Congress and the several States along the lines which separate or distinguish foreign and interstate commerce from intrastate affairs."

Justices Joseph McKenna and John Clarke each wrote dissenting opinions taking issue with the majority's assertion regarding "concurrent power." Justice McKenna believed the term required "united action between the States and Congress, or, at any rate, concordant and harmonious action." Similarly, Justice Clarke asserted that Congress and the states had been granted equal power to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment and that no state could be bound by the Volstead Act without its consent.

The presence of Justices Willis Van Devanter, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Louis Brandeis in the majority on the National Prohibition Cases and the skepticism of Justice James McReynolds—who concurred in the result but found it premature to construe the Eighteenth Amendment before the Court had been called upon to resolve specific controversies—represented those justices' positions on Prohibition generally. During the chief justiceship of William H. Taft, which lasted from 1921 to 1930, that is, for most of Prohibition, the Court was divided into three factions. Three members of the Court—Justices McReynolds, Pierce Butler, and George Sutherland (who succeeded Justice Clarke in 1922)—opposed Prohibition from a traditional conservative point of view. They disfavored a major expansion of federal legislative power and further governmental intrusion into the lives of American citizens. Justice Harlan Stone (who succeeded Justice McKenna in 1925) was not as staunchly opposed to Prohibition but sometimes voted with this bloc of justices. The Court’s other conservatives—Justices Van Devanter and Edward Sanford and Chief Justice Taft—supported enforcement of Prohibition not on policy grounds, but because they saw widespread disobedience to the alcohol ban as a threat to the legal order itself. Justices Holmes and Brandeis were the only members of the Court who supported the expansion of national authority that Prohibition represented and favored deference to this expression of legislative authority.

August 23, 1921: Hiram Walker & Sons v. Lawson

Judge Arthur Tuttle of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan rules in Hiram Walker & Sons, Ltd. v. Lawson that U.S. officials cannot prevent a Canadian distillery from shipping liquor through the United States to Mexico as to do so would violate the terms of an 1871 treaty between the United States and Great Britain. The decision leads to an increase in smuggling of Canadian liquor into the United States, but the Supreme Court reverses it in 1922, holding in Grogan v. Hiram Walker & Sons, Ltd. that such shipments violate the Volstead Act.

Prohibition agents examine barrels on a boat captured by the U.S. Coast Guard, 1924 (Source: Library of Congress)

May 8, 1922: George Remus Goes on Trial

George Remus, a former attorney whose notoriety has earned him the title "King of the Bootleggers," goes on trial in Cincinnati before Judge John W. Peck of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio. Charged with conspiracy to violate the Volstead Act, Remus is convicted and spends two years in a federal penitentiary in Atlanta and then a year in jail in Ohio because the farm from which he ran his bootlegging operation constituted a public nuisance under state law.

Bootlegger George Remus in jail, 1927 (Source: The Mob Museum)

- George Remus (click to learn more)

-

George Remus was a Chicago attorney who left the practice of law in the early 1920s to pursue the economic opportunities presented by Prohibition. He experienced tremendous success in the illegal alcohol trade, earning tens of millions of dollars and living a glamorous and extravagant lifestyle as one of the nation’s most prominent bootleggers. Sometimes referred to as "King of the Bootleggers," Remus was thought by some to have inspired the title character in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby.

Remus made his fortune by setting up a pharmaceutical business and then buying up several whiskey distilleries in the Midwest, ostensibly to use their stocks of liquor for medicinal purposes, which was legal under the Volstead Act. In reality, Remus would have his own shipments hijacked so he could divert the liquor to the bootlegging trade. To better supervise his business operations, he moved to Cincinnati, which was close to many of the government-bonded warehouses (that is, under government supervision) in which his whiskey was legally held.

Although he paved the way for his illegal activities by making extensive bribes to the police and other public officials, Remus was twice indicted for conspiracy to violate the Volstead Act. In 1922, he was convicted in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio and sentenced to two years in federal prison. In 1923, while appealing his conviction, he acted as a ringleader of the conspiracy in the "Jack Daniels Whiskey Case"—one of the biggest bootlegging scandals in American history (see December 14, 1925, below). By the time the Jack Daniels case went to trial in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana in 1925, Remus was serving his federal prison sentence, his appeal of the 1922 conviction having been unsuccessful. He had the new charges against him dropped, however, by testifying against his associates, many of whom were convicted.

While Remus gained notoriety as a bootlegger, he was ultimately remembered best for killing his estranged wife, Imogene, who began an affair with a Prohibition agent while Remus was in prison. The agent, Franklin Dodge, entered the prison while working undercover to befriend Remus and obtain information about his operations and finances. Dodge then used the information for his own purposes, beginning an affair with Imogene and conspiring with her to take control of Remus's fortune. After Remus, a German émigré, was released from prison, the pair attempted unsuccessfully to have him deported or murdered. In 1927, the day his divorce from Imogene was to be finalized in court, Remus followed his wife on her way to the courthouse, forced the car she was riding in off the road, and fatally shot her. Charged with murder, he was acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity. Once committed to a mental hospital, Remus secured his release by arguing that the state of Ohio, which had already deemed him competent to stand trial for murder, was precluded from classifying him as insane.

December 11, 1922: U.S. v. Lanza

In a major victory for Prohibition enforcement, the Supreme Court holds in United States v. Lanza that a defendant may be deemed to have committed multiple offenses by a single act that violates both a state Prohibition law and the Volstead Act. As separate sovereigns, the state and federal governments may both prosecute the same individual for a Prohibition violation without violating the Fifth Amendment's Double Jeopardy Clause. The separate sovereigns or dual sovereignty doctrine has survived, providing a significant example of how Prohibition helped to reshape American constitutional criminal law. While the doctrine was applied frequently in the context of prosecutions by both the federal government and a state, the Court held for the first time in Heath v. Alabama (1985) that it permitted successive prosecutions for the same conduct by two different states as well. (The defendant in Heath was convicted of murder in two states after the victim was kidnapped in one state and discovered dead in another.)

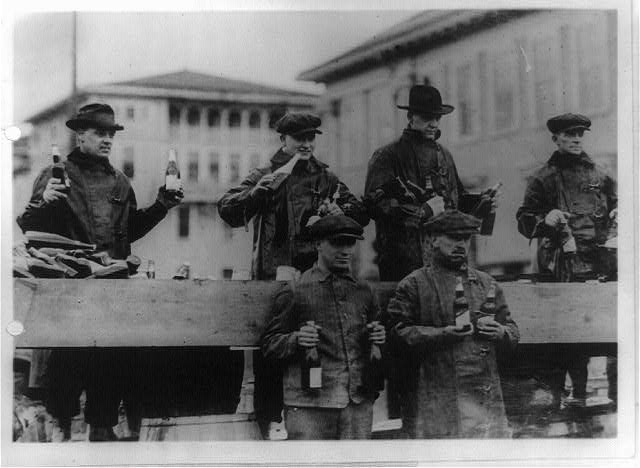

Men pose with bottles of beer intercepted in Zion, Illinois, en route by truck to Chicago (Source: Library of Congress)

May 5, 1924: Hester v. U.S.

The Supreme Court rules in Hester v. United States, a liquor case, that Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure does not extend to open fields surrounding a suspect's house, even if they are part of the same property. In that case, no search took place for Fourth Amendment purposes when revenue officers hid on a suspect's father's land and witnessed the suspect exit the house and hand someone a bottle. The open fields doctrine, which has remained part of Fourth Amendment law, illustrates the Court's willingness to restrict the scope of protection against unreasonable search and seizure to allow for more effective Prohibition enforcement.

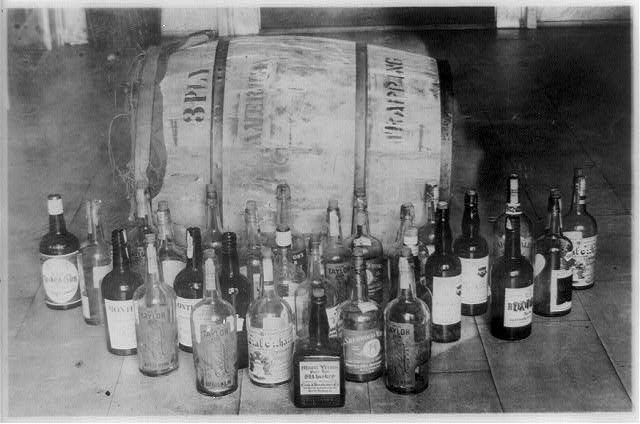

A barrel and several bottles of confiscated whiskey (Source: Library of Congress)

June 9, 1924: Everard's Breweries v. Day

The Volstead Act prohibits the use of alcohol for "beverage purposes." Some other uses of alcohol, such as that for industrial, sacramental, or medicinal purposes, remain legal. In 1921, however, Congress amends the Act to prohibit the use of malt liquors for medicinal purposes. Two plaintiffs—a brewery in New York that produced beer and ale for medicinal purposes and a British bottler and distributor of Guinness stout—sue to enjoin enforcement of the 1921 Act. They argue that the Eighteenth Amendment gives the federal government the authority to ban only liquor used for beverage purposes and that power to regulate liquor used for other purposes remains solely with the states. The Supreme Court upholds the law on the grounds that the Eighteenth Amendment authorizes Congress to enforce the ban on beverage alcohol "by appropriate legislation," which gives Congress discretion as to the most appropriate means to carry out this policy. While legislative discretion is not unlimited, the Court finds that the prohibition on malt liquor for medicinal purposes is related to the beverage ban closely enough to not exceed the limits of that discretion. Finding the law in question to be a reasonable exercise of legislative power, the Court states that it will not second-guess its necessity. The decision is criticized by those who believe it to be an unwarranted expansion of congressional authority over Prohibition enforcement.

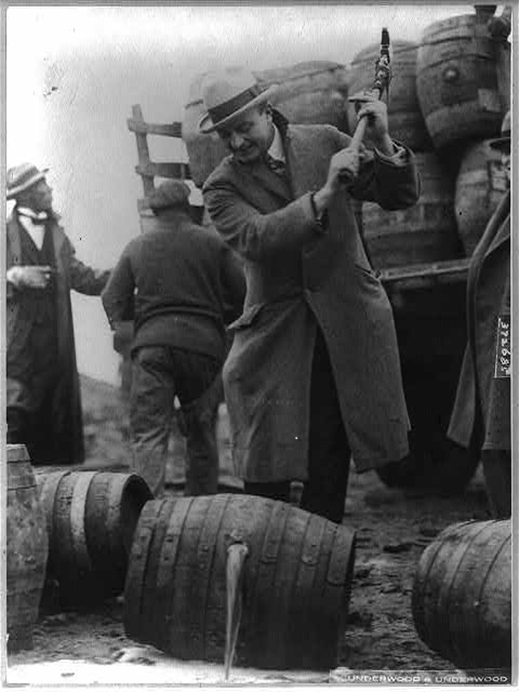

A government official, most likely U.S. Marshal W. Frank Mathues, destroys barrels of beer with an axe in Philadelphia, 1924 (Source: Library of Congress)

February 15, 1925: Judge John McGee

Judge John F. McGee of the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, who once sentenced Prohibition violators so vigorously that he was known as "the bootleggers' terror," takes his own life immediately after writing a letter lamenting the crushing burden of Prohibition cases with "the end not in sight." "I started, in March 1923, to rush that branch of the litigation and thought I would end it, but it ended me," he writes.

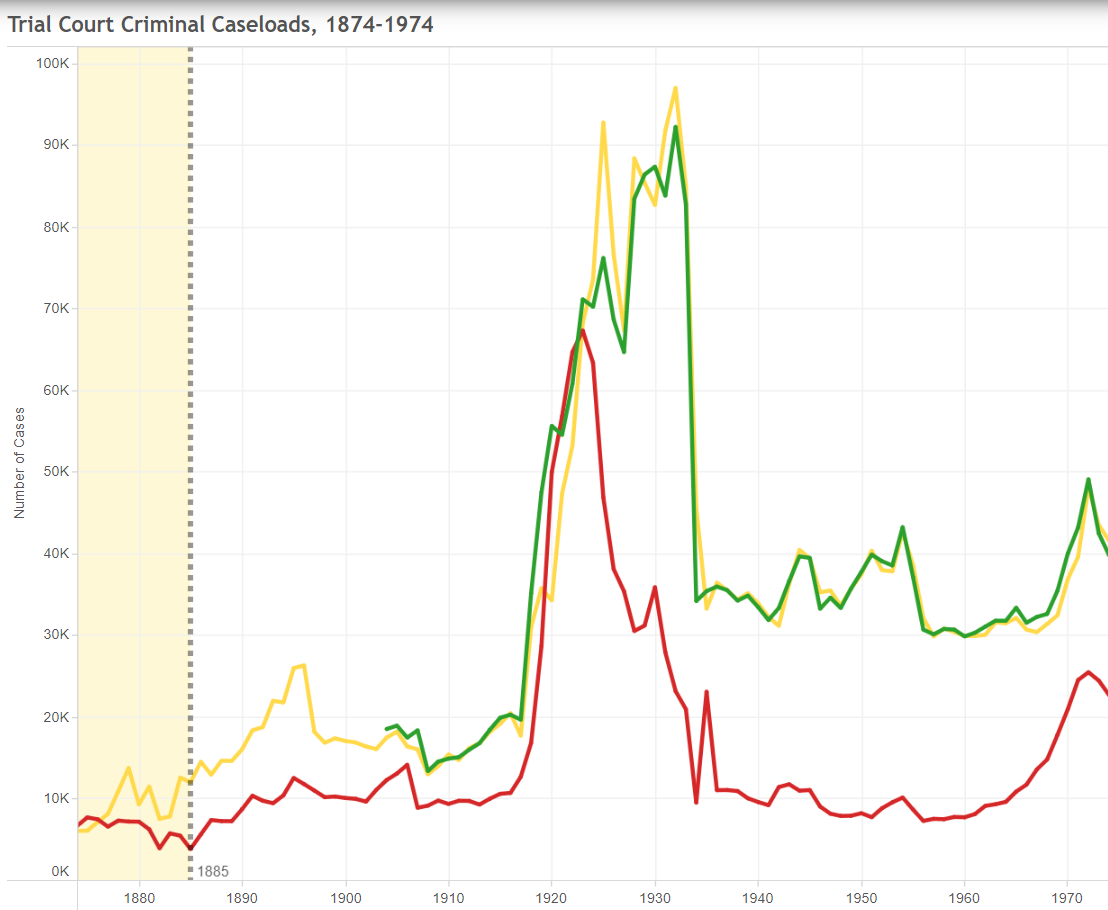

A table of federal criminal caseloads shows a dramatic spike during Prohibition (Source: Federal Judicial Center)

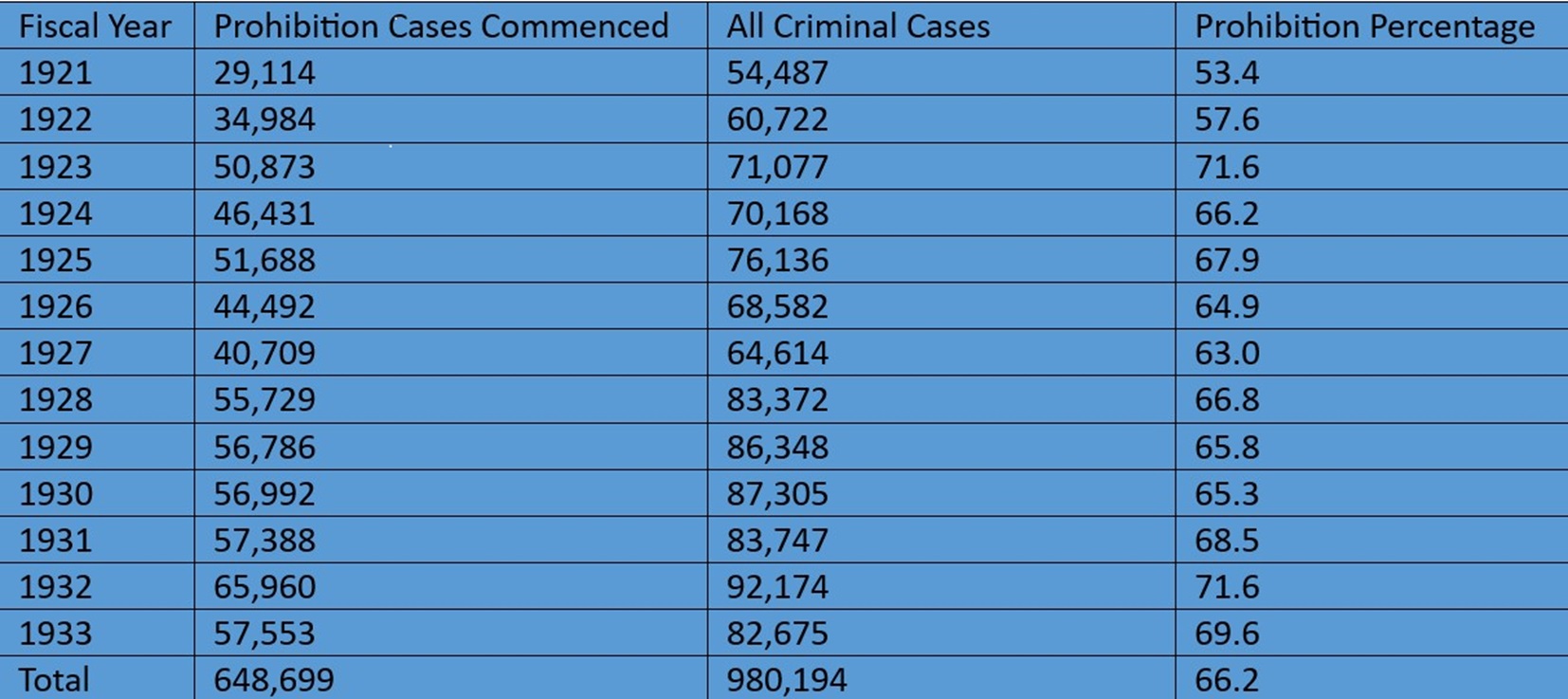

Data from the Annual Report of the Attorney General, 1921-1933

- The Burden of Prohibition on the Federal Courts (click to learn more)

-

Prohibition was a highly consequential policy, representing the most expansive attempt the federal government had ever made to exert control over important details of citizens' everyday lives. Until it was repealed in 1933, the alcohol ban was the most significant factor affecting the federal judiciary. Prohibition flooded the trial courts with criminal cases, straining resources, delaying other work, and spurring a controversial increase in plea bargaining to reduce what would have been an unmanageable number of trials. The prestige of the federal trial courts was undermined, as those courts were tasked with hearing minor criminal cases of a type often handled in low-level police courts in the states. Judge Learned Hand of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (later a prominent appellate judge) spoke for many of his colleagues on the federal bench in calling this development "thoroughly disgusting." Upon taking office as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York in 1925, Emory Buckner called Manhattan’s federal court "whatever is in the subcellar under a police court."

Criminal cases brought under the Volstead Act (over which the federal courts had exclusive jurisdiction) constituted nearly two-thirds of all criminal cases brought in the federal courts from fiscal year 1921, the first full statistical year in which Prohibition was in effect, through fiscal year 1933, the last full fiscal year prior to repeal. Largely because of Prohibition, the number of new criminal cases brought annually more than quadrupled, averaging 75,400 per year between 1921 and 1933, up from an average of 17,269 from 1904 to 1917. (The years 1918–1920 are excluded from this comparison, having been skewed by the large number of World War I draft evasion cases brought in those years, many of which were eventually dismissed.) While Congress created additional U.S. district court judgeships to ameliorate the pressure—raising the number of authorized positions 46%, from 98 in 1921 to 143 by 1931—the increase was not nearly enough. Federal courts remained overwhelmed by the deluge.

The problems associated with enforcing Prohibition extended far beyond its effects on the courts. By the late 1920s, public opinion had turned sharply against the law, disobedience was rampant, law enforcement efforts were plagued by corruption, and some states were reducing their enforcement efforts, putting more of the burden on the federal government. As a result, Congress appropriated funds in 1929 for a "thorough inquiry into the problem" of enforcing Prohibition and other criminal laws. Pursuant to this congressional authorization, President Herbert Hoover established the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement, better known as the Wickersham Commission, after its chair, George Wickersham, who had served as attorney general under President Taft.

In a message accompanying the commission's preliminary report of January 1930, President Hoover noted the commission’s conclusion that Prohibition and other new criminal laws had "finally culminated in a burden upon the Federal courts of a character for which they are ill-designed, and in many cases entirely beyond their capacity." Attorney General William Mitchell's message added that court congestion had brought about "the effort to clear dockets by wholesale acceptance of pleas of guilty, with light punishment. The deterrent effect of speedy trial and adequate punishment is lost."

The Wickersham Commission’s final report was grim about the enforcement of Prohibition as a whole. A consistent theme was the difficulty involved in enforcing a law that contradicted the habits and morals of a large number of Americans and thus produced widespread disobedience. Devoting one section to the federal judiciary, the report called the courts "ill adapted" to enforcing Prohibition, echoing the observations of others that these courts were doing work that was once the province of police courts in the states organized specifically for the purpose of handling minor criminal cases.

The commission also made note of the aforementioned increase in guilty pleas, a phenomenon "disproportionate" in liquor prosecutions. In fiscal year 1930, the report stated, "over eight-ninths of the convictions were of this character." The meager fines and short terms of imprisonment imposed in such cases had, as Attorney General Mitchell had asserted, robbed Prohibition prosecutions of their deterrent effect. The report concluded that the volume of cases coming to the federal courts had "injured their dignity, impaired their efficiency, and endangered the wholesome respect for them that once obtained." The report recommended reforms but stopped short of advocating repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment (a solution Hoover would have adamantly opposed). Nevertheless, it played an important part in ending Prohibition by convincing many that the reforms needed to improve enforcement would be too difficult to achieve.

In fiscal year 1934, the statistical year during which Prohibition was repealed, the total number of criminal cases commenced dropped dramatically, to 34,152 from 82,675 the prior year. From that point, the number of new federal criminal cases exceeded 40,000 only once prior to 1971, providing a stark illustration of the enormous pressure Prohibition had exerted on the federal judiciary.

March 2, 1925: U.S. v. Carroll

The Supreme Court holds in United States v. Carroll that a warrantless search of an automobile is permissible if the police have probable cause to believe it contains alcohol. The opinion, addressing one of the most significant practical difficulties of Prohibition enforcement, leaves a lasting impact on Fourth Amendment law. The vehicle exception to the Fourth Amendment's warrant requirement, as refined by a long line of subsequent cases, remains widely used by law enforcement officials.

A sign used by the Bureau of Prohibition in stopping automobiles suspected of carrying liquor, 1930 (Source: Library of Congress)

- United States v. Carroll (click to learn more)

-

Prohibition led to such vigorous law enforcement efforts to find and confiscate contraband liquor (without which prosecution would have been impossible in most cases) that some legal commentators believed the Eighteenth Amendment to be incompatible with the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable search and seizure. One of the most enduring legacies of Prohibition was the substantial amount of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence the Supreme Court produced under Chief Justice William H. Taft (1921–1930) in an attempt to balance individual rights with the need for effective law enforcement.

According to the exclusionary rule, in effect since Weeks v. United States (1914), evidence could not be used at trial in federal court if it had been seized in violation of a criminal defendant's Fourth Amendment rights. Liquor transported by automobile, an ever more common phenomenon as automobile ownership rose during the 1920s, posed a particular challenge for Prohibition enforcement. Obtaining a warrant to search a car suspected to contain liquor was not practical because the car would be long gone, and its contents disposed of, by the time a warrant could be secured. Law enforcement officials believed that Prohibition would be virtually unenforceable absent the ability to search vehicles for liquor without running afoul of the Constitution. The Supreme Court addressed the inherent tension between Fourth Amendment rights and the practical necessities of Prohibition enforcement in Carroll v. United States (1925).

In an opinion written by Chief Justice Taft, the Court set a new standard for the warrantless search of an automobile, holding that evidence discovered during such a search would be admissible as long as an officer had probable cause, that is, "a belief, reasonably arising out of circumstances known to the seizing officer" that the vehicle contained illicit alcohol. Under this legal standard, courts could allow Prohibition agents wide latitude to conduct warrantless automobile searches and avoid second-guessing an agent's suspicion if it turned out to be correct. The search upheld in Carroll was based on scant evidence, consisting mainly of the facts that agents recognized the car as that of a suspected bootlegger who had promised but failed to furnish whiskey to them months earlier and that the driver was coming from the direction of Detroit, where large quantities of liquor entered the United States from Canada.

Some conservative justices disagreed with the majority's tendency, in Carroll and other cases, to weaken Fourth Amendment protections to better accommodate the exigencies of Prohibition. Justice James McReynolds, consistent with his belief that Prohibition enforcement was infringing unduly on the civil liberties of Americans, dissented in Carroll, joined by Justice George Sutherland. "The Volstead Act," he asserted, "does not, in terms, authorize arrest or seizure upon mere suspicion." Pointing out that criminal statutes were to be construed strictly, Justice McReynolds noted that the Act authorized seizure when an officer "shall discover" a person transporting liquor illegally. Those words, he continued, "cannot mean, shall have reasonable cause to suspect or believe that such transportation is being carried on. To discover and to suspect are wholly different things."

Carroll reflected of the Court's general tendency to allow law enforcement officers greater latitude with respect to search and seizure during Prohibition. The principles established by the majority's opinion stood the test of time, and several scholars have pointed to Carroll as the Prohibition case that left the most lasting impact on Fourth Amendment jurisprudence.

December 14, 1925: The Jack Daniels Whiskey Case

The trial of United States v. Motlow, also known as the "Jack Daniels Whiskey case" begins in Indianapolis before Judge Robert C. Baltzell of the U.S. District Court for the District of Indiana. The alleged conspiracy to remove more than 30,000 gallons of whiskey from the Jack Daniels warehouse in St. Louis, Missouri, for sale on the black market is one of the largest Prohibition cases in history. Convicted bootlegger George Remus is indicted as a ringleader of the conspiracy but has his charges dropped after testifying for the prosecution against his associates. Twenty-four defendants are convicted, although some of the convictions are overturned on appeal.

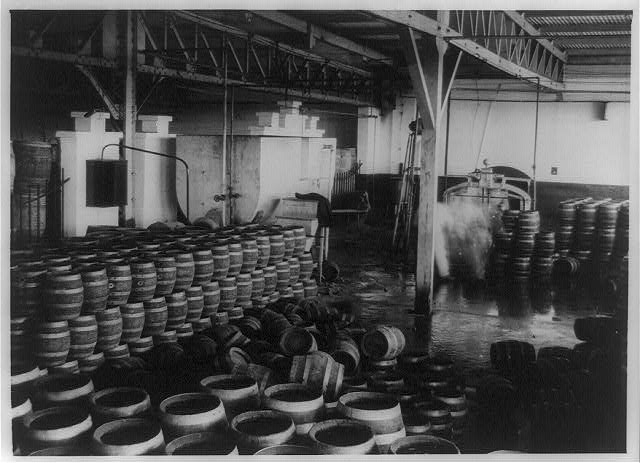

Barrels of liquor, most likely confiscated (Source: Library of Congress)

- The Jack Daniels Whiskey Case (click to learn more)

-

George Remus, the lawyer turned bootlegger who spent two years in federal prison, was at the center of United States v. Motlow, also known as the Jack Daniels Whiskey Case, which involved one of the largest bootlegging operations in American history. In 1923 (while appealing the 1922 bootlegging conviction that would send him to prison), Remus and others purchased the Jack Daniels distillery, which had been relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, when Tennessee became a dry state in 1910. The distillery still owned a large amount of whiskey, which was held legally in a government-bonded warehouse.

Remus planned to have his co-conspirators surreptitiously remove a small amount of whiskey—just six gallons from each of the nearly 900 forty-gallon barrels in the warehouse—for illegal sale. By removing a relatively small amount from each barrel, the bootleggers could replace the missing whiskey with a mixture of alcohol and water, keeping the barrel's proof, or alcohol content, consistent until the next government inspection without ruining the remaining contents.

The other members of the conspiracy disobeyed Remus's instructions, however, draining the barrels completely and replacing their entire contents—more than 30,000 gallons in all—with alcohol and water. A government agent tasting a sample from any of these barrels would immediately realize they no longer contained whiskey, which is exactly what happened. Although the conspirators maintained one full barrel of whiskey to be used in the event of a taste test, none of them was present when a government tester showed up and sampled from a different barrel opened by a night watchman unaware of its contents.

The government was reluctant to try the case in Missouri, as some of the defendants were influential in that state. Instead, the case was brought in the U.S. District Court for the District of Indiana—a state that went dry before national Prohibition—in Indianapolis. That court had jurisdiction over the case because some of the illicit whiskey was intercepted in Indiana as it was being transported from St. Louis to Indianapolis.

More than thirty individuals were indicted for conspiracy in 1925, including George Remus, then serving the federal prison sentence arising from his 1922 conviction. Remus, however, having learned that the other leaders of the conspiracy had been cheating him out of his share of the profits, became a witness for the government and eventually had the charges against him dropped. Twenty-four people were convicted in a trial that gained national attention.

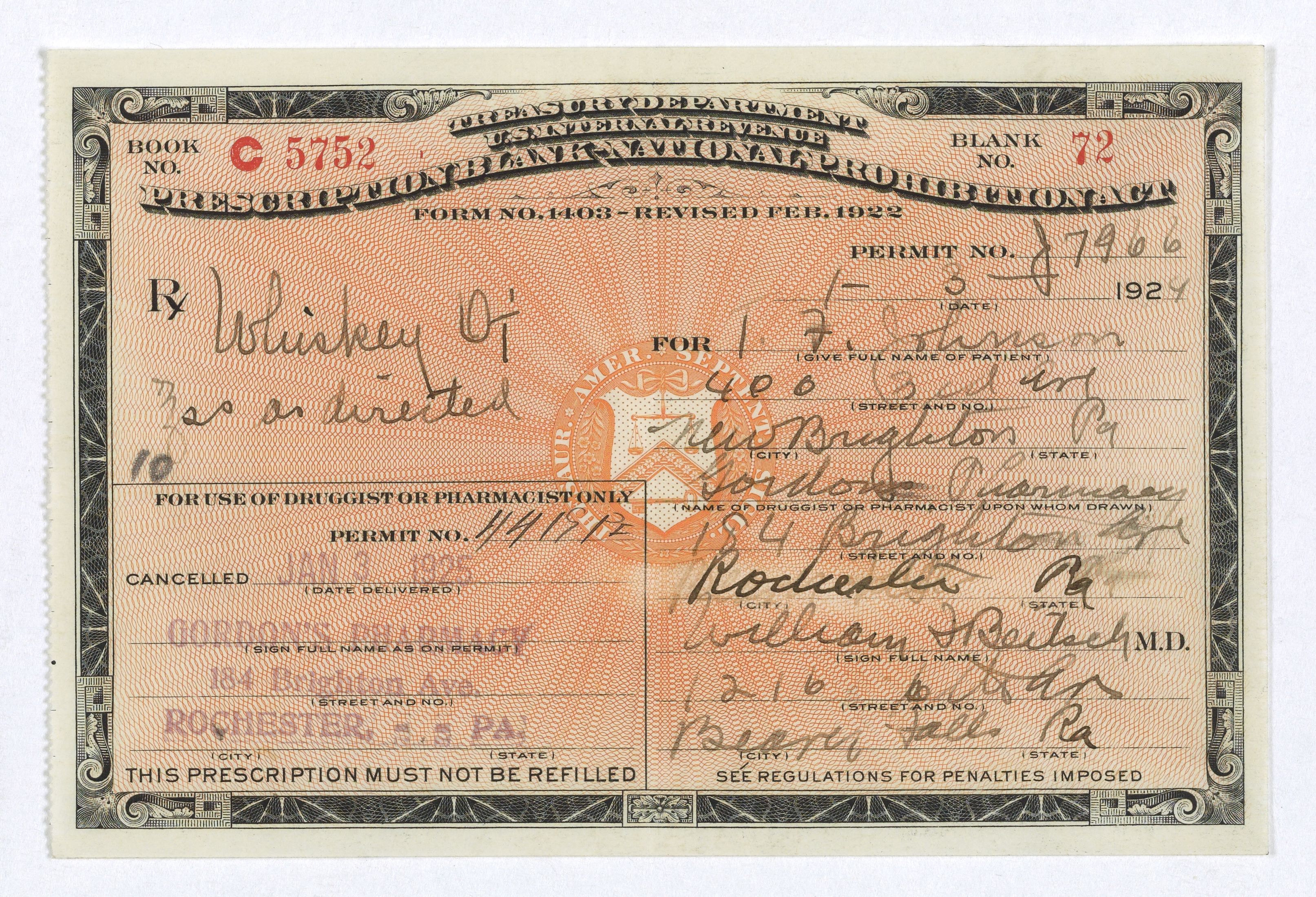

November 29, 1926: Lambert v. Yellowley

In Lambert v. Yellowley, the Supreme Court votes 5–4 to uphold the Volstead Act's restriction on the use of spirits for medicinal purposes to one pint every ten days. The majority asserts that the case is controlled by Everard's Breweries v. Day, in which the Court upheld a ban on the use of malt liquors for medicinal purposes, on the grounds that if Congress can ban medicinal use in some cases, it can surely limit such use in others. The dissenters argue that the Lambert ruling goes far beyond what was established in Everard's Breweries, however. In the earlier case, Congress had determined that malt liquors possessed no medicinal value, a finding the Court declined to question. In contrast, by not banning the prescription of spirituous liquors (a more widely accepted practice) entirely, Congress had made an implicit finding that those liquors possessed at least some medicinal value. The only evidence in the record as to the appropriate quantities to be prescribed, however, came from the plaintiff doctor who asserted that the quantities allowed by law were insufficient. Detractors assert that the Lambert decision is arbitrary and removes virtually all restraints on congressional power to enforce Prohibition.

Prescription for medicinal whiskey (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

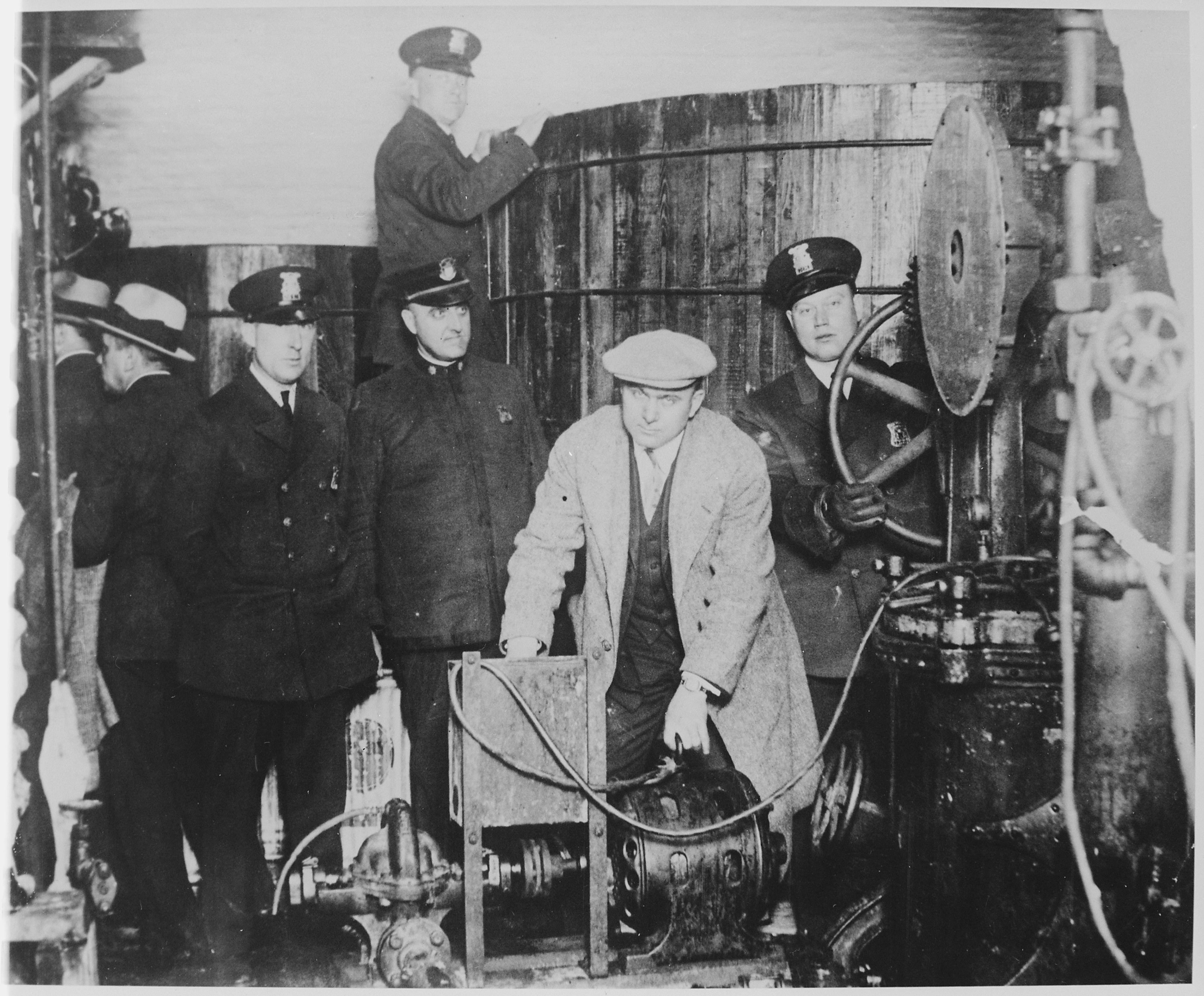

March 7, 1927: Tumey v. Ohio

The Supreme Court holds in Tumey v. Ohio that an Ohio law allowing small villages to establish liquor courts violates the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. The law, which permits village courts to prosecute Prohibition violations anywhere in the same county, entitles the judge and the village to share in revenues from fines, thereby putting decisional power in the hands of those with a financial interest in each case. The village in question, located in Hamilton County, had been funding itself by prosecuting a large number of Prohibition violators from the nearby city of Cincinnati.

Detroit police inspect equipment discovered in an underground brewery (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

May 16, 1927: U.S. v. Sullivan

The Supreme Court rules in United States v. Sullivan that requiring the filing of a tax return for income derived from bootlegging does not intrude on the Fifth Amendment's protection against compelled self-incrimination. The ruling becomes the basis for the government's prosecution of Al Capone on tax evasion charges.

New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach watches agents pour liquor into a sewer following a Prohibition raid (Source: Library of Congress)

June 4, 1928: Olmstead v. U.S.

The Supreme Court upholds the conviction of Seattle bootlegger Roy Olmstead, holding in Olmstead v. United States that the warrantless wiretapping of his telephone calls does not violate the Fourth Amendment because the police did not enter his premises or confiscate his property; therefore, no search or seizure took place. The decision is widely criticized because of an unfavorable view of wiretapping among the public as well as the allegation that the Court has condoned official lawlessness by approving wiretapping that violated Washington state law. Because of the stigma surrounding wiretapping, the decision does not have a major effect on Prohibition enforcement. In 1934, Congress passes the Federal Communications Act, which the Court interprets to prohibit warrantless wiretapping by federal agents. The Supreme Court overturns the Olmstead ruling that the Fourth Amendment protects only against physical intrusion in Katz v. United States (1967).

Roy Olmstead and his wife, Elsie (Source: Seattle Museum of History and Industry)

- Olmstead v. United States (click to learn more)

-

Roy Olmstead, a former Seattle police officer (he left the force after pleading guilty to bootlegging in 1920), led a successful criminal enterprise that illegally imported alcohol from Canada in ships supposedly bound for Mexico. Using his connections with the local police, Olmstead built a large criminal network that was difficult for federal authorities to break using traditional law enforcement techniques. In 1924, federal investigators resorted to wiretaps of telephones at Olmstead's home and office—in violation of Washington state law—to capture incriminating information. In combination with evidence obtained through Canadian police, the wiretapped information eventually led to the seizure of records supporting charges of conspiracy to violate the Volstead Act against Olmstead and dozens of other defendants.

At trial, the transcripts of the wiretapped conversations were not themselves admitted into evidence, though witnesses used them to refresh their recollections while testifying, and District Judge Jeremiah Neterer permitted the admission of records and of other incriminating evidence obtained as a result of the wiretaps. Olmstead was convicted and sentenced to four years imprisonment and an $8,000 fine. On appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Olmstead's lawyers argued that the wiretaps, and the use of any evidence obtained through them, violated the Fourth Amendment's prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures and the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination. The appeal was unsuccessful, however, as a panel of Ninth Circuit judges ruled against Olmstead by a 2–1 vote.

Olmstead appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States and, again, a divided Court ruled against him. Chief Justice William Howard Taft emphasized that government agents had not physically entered Olmstead's home or office and reasoned that the Fourth Amendment "can not be extended and expanded to include telephone wires reaching to the whole world from the defendant's house or office. The . . . wires are not part of his house or office any more than are the highways along which they are stretched."

Justice Louis Brandeis wrote the most famous and legally significant of the four dissenting opinions. The Fourth and Fifth Amendments, Justice Brandeis argued, reflected a wide-ranging concern with excessive government intrusion against privacy and should not be interpreted too narrowly or too literally. It was misguided, he reasoned, to expect the authors of these amendments to have anticipated modern innovations like the telephone. Similarly, he reasoned that the Fifth Amendment should not be limited to self-incrimination by physical coercion. Modern technology had opened up new means, including phone taps, for the government to procure self-incriminating evidence against an individual's will.

In 1934, Congress passed the Federal Communications Act, which provided that "no person not being authorized by the sender shall intercept any communication and divulge or publish the existence, contents, [or] substance." In Nardone v. United States (1937), the Supreme Court interpreted the statute to prohibit warrantless wiretapping by federal agents.

Although Brandeis was in the minority in Olmstead, his view of the right to privacy eventually won over a majority of the Court. In Katz v. United States (1967), the Court ruled evidence obtained through a device attached to a public telephone booth inadmissible based on a telephone caller’s reasonable expectation of privacy.

February 14, 1929: The St. Valentine's Day Massacre

In one of the worst episodes of Prohibition-related violence, seven men are lined up against the wall of a Chicago garage and shot by men disguised as police officers. Two of the four assailants are armed with submachine guns. The perpetrators of what the press dubs the "St. Valentine's Day Massacre" are never identified, but many suspect gangster Al Capone to be behind the attack that killed five associates of his rival George "Bugs" Moran. The association between Prohibition and gang violence helps to weaken public support for the alcohol ban.

Prohibition officers raid a lunchroom in Washington, D.C., in 1923 (Source: Library of Congress)

March 2, 1929: Increased Penalties Act

With Prohibition enforcement lagging and the public calling for a clampdown on crime, Congress decides to increase criminal penalties for liquor offenses. The Increased Penalties Act (or Jones Act) amends the Volstead Act, most notably by converting first offenses for manufacturing, transporting, or selling liquor from misdemeanors to felonies punishable by a fine of up to $10,000 and a prison term of up to five years. The law states that in making sentencing decisions, the federal courts should "discriminate between casual or slight violations and habitual sales of intoxicating liquor, or attempts to commercialize violations of the law." Despite this congressional admonition, the federal courts apply the Act's penalties strictly, leading to criticism of the law as overly harsh and to a backlash even among some Prohibition supporters.

Senator Wesley L. Jones of Washington, one of the sponsors of the Increased Penalties Act (Source: Library of Congress)

May 28, 1929: Wickersham Commission

On March 4, 1929, as a result of rampant disobedience of Prohibition laws and the belief of many in government that enforcement has been ineffective, Congress appropriates funds for a "thorough investigation" of the issue. On May 28, President Herbert Hoover appoints the National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement (better known as the Wickersham Commission, after its chair, former attorney general George W. Wickersham) to carry out the study. In a preliminary report to the president issued on November 21, the commission put forth several legislative proposals to reduce court congestion caused by Prohibition.

President Herbert Hoover (Source: White House)

- Legislative Proposals to Reduce Court Congestion (click to learn more)

-

In late 1929, the Wickersham Commission proposed several pieces of legislation meant to work in conjunction to reduce the court congestion caused by Prohibition. The first, enacted in December 1930, amended a section of the U.S. criminal code to define "petty offenses." Previously, the code had defined offenses punishable by death or more than one year in prison as felonies and all other offenses as misdemeanors. The amendment specified that any misdemeanor for which the sentence did not exceed six months in jail without hard labor or a fine of $500 would be termed a petty offense. Petty offenses, according to the amended statute, could be prosecuted by information (that is, on the initiative of a prosecutor) rather than requiring an indictment by a grand jury.

The classification of some crimes as petty offenses was meant to work in harmony with another statute reducing penalties for certain minor Prohibition violations. The Increased Penalties Act of 1929 (or Jones Act) had strengthened some of the maximum punishments provided by the Volstead Act. Although Congress expressed in the Act the hope that courts would "discriminate between casual or slight violations" and more serious ones, courts applied the increased penalties more strictly than Congress had intended. As a result, Congress amended the Increased Penalties Act in January 1931, giving precise definitions to casual or slight violations. These offenses included manufacturing or selling liquor not exceeding one gallon in quantity, assisting in making or transporting liquor "as a casual employee only," and transporting liquor not exceeding one gallon "by a person not habitually engaged or employed" in activities that violated Prohibition. By making the maximum penalty for these offenses a fine of $500 or six months in jail without hard labor, the law converted these crimes to "petty offenses" under the terms of the statute it had enacted the previous month.

The most complex and controversial piece of the puzzle was a proposal that would have provided for "summary prosecution" of petty offenses. The plan relied on U.S. commissioners, officers of the U.S. district courts who were the forerunners of modern U.S. magistrate judges (though not deemed judges and having far fewer powers). The bill provided that a defendant who pleaded not guilty would have a hearing before a commissioner who would then make a report to the court and recommend for or against conviction. The accused could demand a trial by jury in two circumstances: if the commissioner recommended conviction or if a district judge disapproved a commissioner's recommendation of acquittal and found the defendant guilty.

Proponents of the bill believed that disposing of minor criminal cases in summary fashion would increase efficiency and allow courts to clear the backlog that Prohibition had created. Opponents of the bill asserted that on the contrary, it would cause only delay and confusion. In a minority report opposing the bill, four members of the House Judiciary Committee called its provisions "circuitous" and "indirect." The bill sought to make trial judges out of commissioners, they asserted, but still required district judges to pore over the entire record of a case to determine whether to accept or reject the commissioner's recommendation.

More importantly, the committee members in the minority believed the bill to be unconstitutional. "The defendant cannot be deprived of a jury trial in the first instance, and the defect is not cured by the remote and technical right of a jury trial provided in the bill," they wrote. While the federal courts recognized the existence of a category of minor offenses not covered by the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, it was not until the 1960s that the Supreme Court defined such offenses as those subject to less than six months' imprisonment. As a result, it was uncertain whether the courts might hold the summary prosecution bill to violate the Sixth Amendment. Because of concerns as to its efficacy and constitutionality, the bill failed to pass, leaving unfinished the Wickersham Commission's plan to improve the federal courts' handling of Prohibition cases.

May 14, 1930: Federal Bureau of Prisons

Congress establishes the Federal Bureau of Prisons to manage a federal prison system experiencing rapid growth in large part because of Prohibition. The average daily prisoner population in the federal system increases from 3,720 in 1920 to 13,352 in 1933, the final year of Prohibition. Despite the repeal of Prohibition, rates of incarceration continue to rise before leveling off after 1940. Throughout the 1930s, many Prohibition violators remain behind bars while prosecutions for other crimes, such as drug and tax offenses, increase.

Sanford Bates, the first director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (Source: Federal Bureau of Prisons)

January 7, 1931: Wickersham Commission Report

The Wickersham Commission issues its final report, which is highly critical of Prohibition enforcement. Among the commission’s many findings is that the federal courts are "ill adapted" to enforcing prosecution, having been forced into doing work once the province of police courts in the states organized specifically for the purpose of handling minor criminal cases. The volume of cases coming to the federal courts, the report concludes, "has injured their dignity, impaired their efficiency, and endangered the wholesome respect for them that once obtained." The litany of problems the commission identifies, as well as the extensive list of reforms it recommends, helps to convince many that Prohibition is unworkable and contributes to its eventual repeal.

George W. Wickersham (Source: Library of Congress)

October 6, 1931: Al Capone Goes on Trial

Legendary bootlegger and gangster Al Capone goes on trial for tax evasion in Chicago before Judge James H. Wilkerson of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois. Although the government is never able to convict him of violating Prohibition laws, Capone spends more than seven years in prison after being convicted of the tax charges.

Al Capone (Source: Library of Congress)

- Al Capone (click to learn more)

- Al Capone was the most notorious gangster of the Prohibition era, leading a violent and ruthless syndicate between 1925 and 1931 that by some estimates made over $100 million per year, primarily from bootlegging and gambling. Despite his prominence, his great wealth, and the frequent murders of rival gangsters carried out at his behest, Capone was never successfully prosecuted for bootlegging, extortion, racketeering, or murder. Instead, the U.S. government eventually proved that Capone had failed to pay taxes on the income from his illegal operations.

- Initially, Capone pled guilty based on an agreement with the government that he would serve two and a half years in prison, but he switched his plea to not guilty when Judge James H. Wilkerson of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois rejected the deal, insisting that Capone would not be permitted to bargain with the court. Before trial began, an informant presented one of the Treasury agents who had investigated the case with evidence that Capone had tampered with the jury pool. As a result, Judge Wilkerson switched his jury pool with that of another judge who was also about to begin a trial. Because of the large amount of evidence meticulously gathered by Treasury agents during their lengthy investigation, Capone was convicted on several counts of federal income tax evasion on October 18, 1931. Judge Wilkerson sentenced him to eleven years in prison. Capone was released in 1939 but was in poor health and never resumed leadership of his gang, which had followed the trend of others involved in organized crime by turning to alternative sources of illegal income such as gambling, drugs, and prostitution. He died in 1947 at age 48.

July 2, 1932: F.D.R. Supports Repeal

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's support for the Prohibition repeal plank of the Democratic Party platform is crucial to his securing his party's nomination for president. Accepting the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he declares, "This convention wants repeal. Your candidate wants repeal. And I am confident that the United States of America wants repeal."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (Source: Library of Congress)

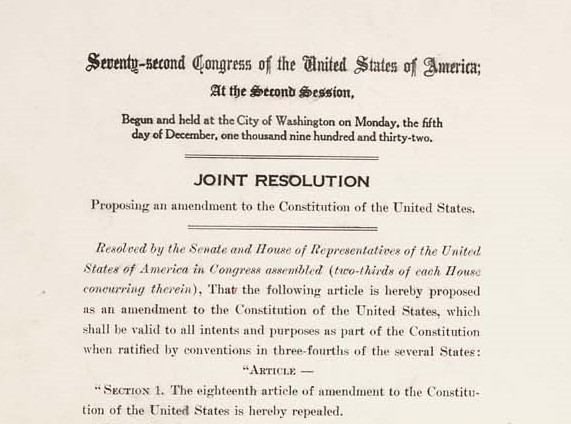

February 14 and 16, 1933: Twenty-First Amendment

With political winds having shifted because of a multitude of factors, including increasing public hostility to Prohibition, the problems with enforcement detailed by the Wickersham Commission's report, and the economic crisis of the Great Depression, the newly elected Senate and House vote to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment by votes of 63–23 and 289–121, respectively.

The Twenty-First Amendment (Source: National Archives and Records Administration)

December 5, 1933: Prohibition Repealed

Utah becomes the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Twenty-First Amendment, giving the amendment the approval of the requisite three-fourths of the states. The Twenty-First Amendment repeals the Eighteenth Amendment, officially ending Prohibition. It also replaces the Eighteenth Amendment as the most quickly ratified constitutional amendment in history.

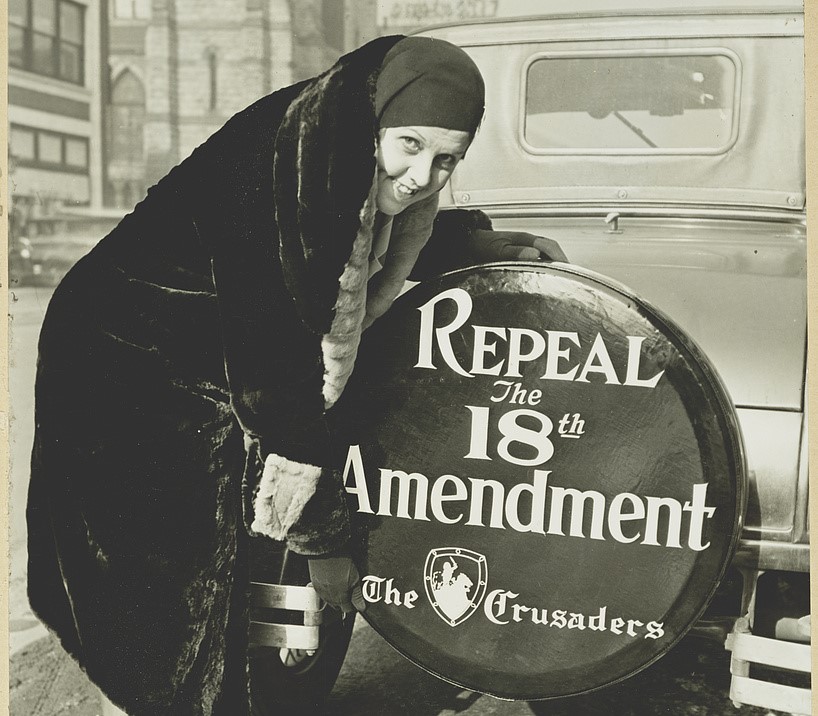

A member of The Crusaders, a national organization advocating the repeal of Prohibition, places a tire cover with an anti-Prohibition message on her car, 1930 (Source: Library of Congress)

While many popular histories of Prohibition do not include a significant focus on the federal courts, there is a consensus among scholars of legal and judicial history that Prohibition was highly consequential for the federal judiciary. The courts suffered from a crushing workload and a blow to their prestige that ended only with Prohibition's repeal. The impact of Prohibition did not dissipate entirely, however, as some of the principles established in that era have remained alive in federal case law.