You are here

Science Resources: Water and the Law

How Much Water Is Used?

Hydrologists use specific terms to describe where, when, and how much water is “used.” Water withdrawals are the total amount that a user removes from a source like a lake, river, or aquifer. In many cases, part of this water flows back into the stream after it has been used (and possibly treated). This water is known as return flow. Water that is removed for use and not returned to the original source is called consumption. Importantly, differentiating water that is withdrawn from water that is consumed is a matter of scope: a flow may return not to the same small stream it was taken from but downstream into a much larger river system. Water that is lost to the atmosphere through evaporation or transpiration from the leaves of vegetation is almost always considered consumed, as is water extracted from an aquifer [18].

The difference between consumption and withdrawal is evident when we consider the largest withdrawers versus the largest consumers of water in the United States. Thermoelectric (thermal) power plants—plants that generate electricity through the burning of coal, oil, or natural gas to create steam to turn a turbine—withdraw water from nearby bodies of water as coolant. In “once-through” system plants, some of this water is lost to the atmosphere through evaporation, but the vast majority returns to the waterway at an elevated temperature [19]. Section 303 of the Clean Water Act regulates this so-called thermal load, which can have significant impacts on downstream aquatic ecosystems [6].

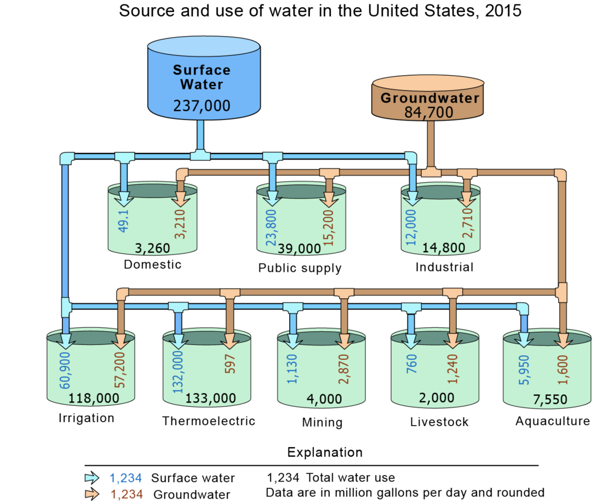

Water demands evolve continually as land use patterns, technology, and consumer behaviors change over time. Agriculture withdraws the greatest share of fresh water in the country (irrigation makes up 42 percent of all freshwater withdrawals), followed closely by thermoelectric power generation (34 percent of all freshwater withdrawals). Public supply makes up the distant third [20].

On the other hand, although agriculture remains the largest consumer of fresh water by sector, thermoelectric power consumes significantly less: in 1995, agriculture comprised 85 percent of total U.S. water consumption, while thermal power generation was only 3 percent [21].

Water rights can be based on diversion (withdrawal) or consumption. The distinction is important. Evaluating both water withdrawal and water consumption are essential to appropriately managing water resources. Understanding water withdrawals allows water resources managers to respond to the competition for scarce resources and the dependence of certain actors on those resources. Measuring water consumption lets us estimate long-term scarcity and evaluate the impact of water withdrawals on downstream uses.

[6] R. Percival, C. Schroeder, A. Miller and J. Leape, Environmental Regulation: Law, Science, and Policy, 9th ed., Boston, MA: Aspen Publishing, 2021.

[18] I. de Graaf, “What is the difference between ‘water withdrawal’ and ‘water consumption’, and why do we need to know?,” June 26, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.agu.org/waterunderground/2017/06/26/difference-water-withdrawal-water-consumption-need-know/. [Accessed June 30, 2022].

[19] T. Cech, Principles of Water Resources: History, Development, Management, and Policy, 3rd ed., Wiley & Sons, 2009.

[20] C. Dieter, et al., “Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1441,” U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C., 2018.

[21] World Economic Forum, “Thirsty Energy: Water and Energy in the 21st Century,” World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.