You are here

Science Resources: Water and the Law

What is Flooding?

Flooding is the overflow of water onto land that is normally dry. However, not all events that cause elevated water levels are categorized as “floods” from a natural disaster perspective. Floods are categorized as such if they impact the public in some fashion: flood forecasters are interested in potential human impact, rather than flooding as a purely meteorological phenomenon.

Floods are among the most common natural disaster: 75 percent of all presidential disaster declarations are associated with flooding [42]. There are five main types of flooding, characterized by the speed, location, and process through which the flood occurs: flash, riverine, urban, lake, and coastal.

- 1. Flash Flooding

-

Flash floods typically develop within less than six hours of the immediate trigger event. Because they occur so quickly, flash floods are often difficult to predict far in advance. Many events can trigger a flash flood, which may be made worse by elements of local geography such as steep channel slopes, lack of vegetation, or large amounts of impervious surface. Flash floods are characterized by high velocities of water, large amounts of debris, and a rapid rise in water levels. The high channel velocities typical of flash flooding make them much more destructive than other types of floods, with vehicles caught in flash floods routinely being washed away [12].

- 2. Riverine Flooding

-

Riverine floods are the most common type of flood in the United States [12]. Most riverine floods are characterized by overbank flooding caused by increasing volumes of water within a river channel that eventually spills over into the floodplain.

The depth and velocity of water in a riverine flood depends on the nature of the river and its floodplain. Some rivers flow through steep, v-shaped valleys, while others may have floodplains that are wide and flat. Although the velocity of floodwaters on a flat floodplain may not be as high as those on a steep one, the water will cover a larger surface area and will take longer to recede [12].

- 3. Urban Flooding

-

According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, urban flooding is “the inundation of property in a built environment, particularly in more densely populated areas, caused by rain falling on increased amounts of impervious surfaces and overwhelming the capacity of drainage systems.” Urban flooding is sometimes called localized flooding [13].

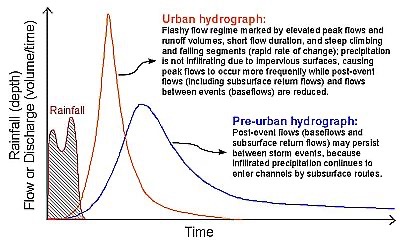

In undeveloped areas, rainfall can infiltrate into the ground or be returned to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration from vegetation. Only a small fraction of that rainfall runs off the surface of the ground, eventually making its way into rivers and streams. In an area with lots of paved surfaces, rainfall does not have a chance to infiltrate [12].

This excess water can cause localized flooding in low-lying areas. Most cities are designed to channel water into underground sewer pipes to prevent water from ponding on streets and sidewalks. However, this channelization concentrates and speeds up flows, creating runoff hydrographs that have short-duration, high-intensity peaks. These flashy hydrographs can create significant flooding challenges for downstream locations if not properly managed [13].

- 4. Lake (Lacustrine) Flooding

-

Lake flooding can be both seasonal and long-term. In the Great Lakes, for example, lake levels typically peak in summer and are at their lowest in winter. Storms or spring snowmelt can drive increases in water level [12].

Long-term fluctuations in lake levels can last years or even decades [14]. Lakes that do not have an outlet, such as playa lakes in the desert Southwest, sinkhole lakes in the Southeast, and oxbow lakes in the Mississippi floodplain, are particularly susceptible to these fluctuations. Other closed basin lakes may have outlets that are too small to adequately maintain a balance between inflow and outflow of water, particularly during extreme events. The Great Lakes (and other inland lakes formed by glacial action) are examples of such a system [12].

-

5. Coastal Flooding

-

Coastal regions are prone to flooding from storm surges and tidal flooding, both of which are exacerbated by rising sea levels in most locations.

Storm surges are created when a low-pressure area inside a tropical storm or hurricane creates a dome of water that increases water surface elevations beyond normal tide levels. As the storm nears the shore, winds push this dome of water up onto the shore, creating surges up to 25 feet high [12]. The size of the surge is calculated by subtracting the standard tide elevation from the observed water elevation. A storm surge’s size and destructive potential are determined by the magnitude of the storm, the slope of the sea floor, the shape of the shoreline, the height of the normal tide, and the direction the storm is traveling relative to the coast. The increased sea levels caused by storm surges allow waves and debris to batter coastal structures they would not otherwise be able to reach, resulting in extensive damage. Hurricane Sandy generated a nine-foot-high storm surge during astronomical high-tide that led to extensive damage across Manhattan and other New York City boroughs [15].

Tidal flooding, also known as sunny day flooding or nuisance flooding, is the temporary inundation of low-lying coastal areas during high tide. While tidal flooding is not nearly as catastrophic as storm surge flooding, repeated tidal flooding leads to road closures and infrastructure deterioration. Tidal flooding also can overwhelm existing storm drainage systems, exacerbating the effects of what would otherwise be relatively minor storm events. The National Ocean Service estimates that tidal flooding has increased in the U.S. by about 50 percent compared to twenty years ago, particularly along the East Coast and the Gulf Coast [16].

[12] J. Wright, “Types of Floods and Floodplains,” in Floodplain Management: Principles and Current Practices, Washington, D.C.: Federal Emergency Management Agency Emergency Management Institute, 2007, pp. 2-1–2-18.

[13] G. Galloway, et al., “The Growing Threat of Urban Flooding: A National Challenge,” University of Maryland, College Park, and Texas A&M University, Galveston, 2018.

[14] United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Climate Change Indicators: Great Lakes Water Levels and Temperatures,” July 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/great-lakes. [Accessed June 6, 2022].

[15] NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, “State of the Climate: Monthly National Climate Report for October 2012,” November 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/national/2012/10/supplemental/page-7/. [Accessed June 6, 2022].

[16] National Ocean Service, “What is high tide flooding?,” Feb. 26, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/high-tide-flooding.html. [Accessed June 6, 2022].

[42] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Guidance for Considering the Use of Living Shorelines,” NOAA, Washington, D.C., 2015.