Age and Experience of Judges

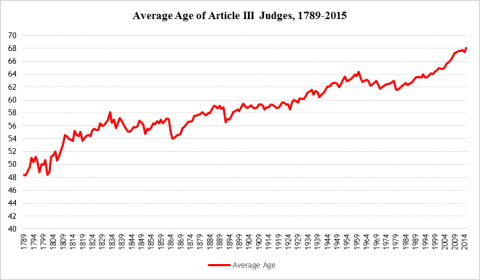

Under Article III, section 1 of the Constitution, Article III judges “hold their offices during good behavior,” which in practice means that many such judges have long careers on the bench. The average age of serving Article III judges has generally risen over the course of American history. This trend appears to reflect both the age at which judges were appointed and broader external changes such as increasing life expectancy. The chart below illustrates the average age of sitting Article III judges over time. [1]

The average age at which judges were appointed to Article III posts was generally more prone to change in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries than it has proven since. This increasing consistency may be partially attributable to the greater number of judges appointed in later years, limiting the influence of statistical outliers. Though some fluctuation remains, modern presidents have generally appointed slightly older individuals to federal judgeships than did the earliest presidents. The chart below reflects these trends.

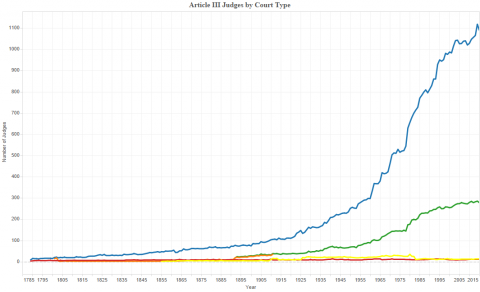

Even in the nation’s early history, federal judges frequently served on the bench for several decades. The following chart tracks the longevity of judges’ terms on the bench, beginning at their commission date (or appointment date in the case of judges who received a recess appointment and were not subsequently confirmed by the Senate). You can search for an individual judge or filter by appointing president or court type using the the menu to the right of the chart. The use of appointing presidents is for ease of visual and historical reference only and should not be taken as an indication of the influence of any president over the judiciary. Readers viewing a large number of judges or seeking detailed information about an individual judge may find it helpful to expand the chart to a full-screen view.[2]

The “good behavior” standard has meant that the overwhelming majority of Article III judges have ended their service either through voluntary retirement, resignation or death. Only eight of these judges have been impeached by the House of Representatives and convicted by the Senate (for further information, see Impeachments of Federal Judges).

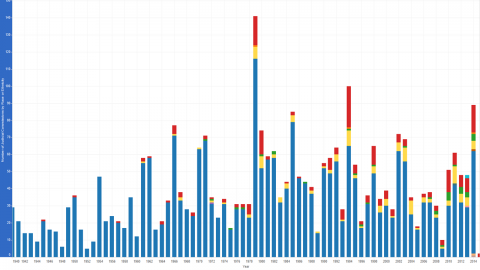

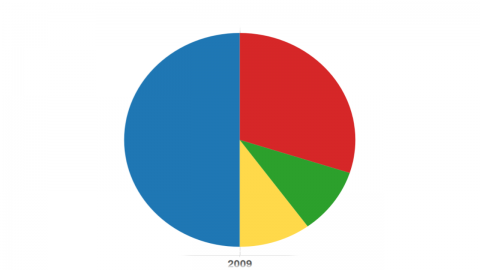

Over time, fewer Article III judges have resigned their posts and more have retired or died in office. Several intangible factors, such as the growing prestige of federal judicial positions, could explain this phenomenon. It is also important to note, however, that Congress only created the option for federal judges to retire with salary in 1869. The chart below shows the ways Article III judges have left the judiciary over time.[3] The unusually high number of resignations in 1861 was due to several judges leaving their positions at the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War to join the Confederate cause. The unusually high number of terminations through court abolition in 1802 was due to the repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801.

Since 1919, Congress has authorized “any judge other than a justice of the Supreme Court” to retire “from regular active service” after the attainment of certain age and service requirements.[4] This option, widely known as “senior status,” enables judges to continue hearing cases with a reduced workload instead of retiring entirely. Congress extended a similar option to Supreme Court justices in 1937, although justices following this path are generally referred to as “retired,” rather than “senior,” justices and do not continue to decide cases at the Supreme Court level.

Initially, senior status was available to judges who had reached the age of 70 and had served on their courts for at least 10 years. In 1984, Congress modified this standard in favor of the so-called “Rule of 80.” Under this rule, judges may assume senior status at age 65 provided they have served at least 15 years on the bench. The service requirement is lowered by one year for each year of age thereafter, such that the judge’s age plus his or her term of service must total at least 80. The Rule of 80 is capped at the original standard of 70 years of age and ten years of service.[5]

In recent decades, many federal judges have assumed senior status even though eligible for full retirement. This trend may help account for the growing proportion of judges whose terms have ended in death rather than resignation or retirement (see previous chart). Though ostensibly retired from “active” service, senior judges continue to do considerable work for the judiciary as a group. From 1997 to 2015, for example, figures from caseload reports of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts indicate that senior-status judges presided over between approximately 15 and 25 percent of all completed district court trials.[6]

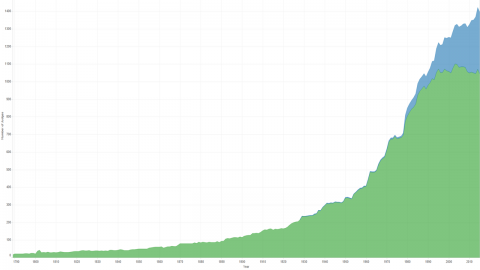

The following chart depicts the number of judges assuming senior status in each year since 1919. The second chart reflects the total number of judges who were on senior status during any part of each year that status was available.[7]

[1] Age charts do not distinguish between judges on “senior” and “active” status as senior judges continue to hold their offices and may conduct judicial business during good behavior. Age statistics are based on the year of birth as the Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges does not list the exact dates of birth of living judges.

[2] This chart defaults to displaying the later of two consecutive judicial posts held in the same year. District judges George Tanner and Susan Wright served in two districts simultaneously for part of their first year of judicial service and were subsequently reassigned during that year to a single district. The chart reflects the service in both districts for those years. District Judge William Gray served in two districts consecutively in his first year of judicial service. The chart also reflects this service, along with the dates of his initial commission and reassignment. From 1891 to 1911, several judges served simultaneously on U.S. circuit courts and U.S. courts of appeals. By default, this chart displays these judges as serving on U.S. circuit courts until 1911 and thereafter as serving on U.S. courts of appeals to reflect the abolition of the U.S. circuit courts. Readers can view the entire U.S. court of appeals service for these judges by de-selecting "U.S. circuit courts" in the "Court Type" menu. For detailed information about judges' service and appointment records, readers may find it helpful to view the judges' entries in the Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges.

[3] This chart reflects the final termination of a judge's career in the judiciary and thus does not refer to the end of judicial commissions due to reassignment, appointment to another judicial position or abolition of a court (although it does count those judges whose final judicial commissions were terminated as a consequence of court abolition). The assumption of senior status is not included as a form of termination.

[4] 40 Stat. 1157 (1919).

[5] See 98 Stat. 350 (1984).

[6] See Judicial Business of the United States Courts, Administrative Office of the United States Courts, 1997-2015.

[7] Thus, for example, the entry for 2020 reflects both judges whose senior status terminated in 2020 and those who remained on senior status into the following year.