Historical Context

In setting forth a plan for the federal judiciary, the framers of the Constitution provided for federal judges to serve “during good behavior” and to receive a salary that could not be diminished. These protections, found in Article III, were designed to ensure that judges would remain independent of the political branches of government. Judges who made unpopular decisions would not fear reprisals in the form of removal from office or diminution in compensation.

Early in the nation’s history, however, the Supreme Court established that Congress could, under certain circumstances, create federal courts whose judges were not cloaked with the tenure and salary protections of Article III. In Canter v. American Insurance Company, decided in 1828, the Court held that the mandates of Article III did not apply to territorial courts. In that case, Chief Justice John Marshall drew a distinction between “constitutional courts,” established under Article III to exercise the judicial power of the United States, and “legislative courts,” which were created to carry out functions delegated to them by Congress. It remained to be seen, however, whether Congress would create legislative courts in other contexts, and if so, whether the Supreme Court would find those courts to be constitutionally capable of carrying out the tasks they had been assigned.

In the ensuing years, Congress established several federal courts charged with exercising specialized jurisdiction. One such specialized court was the Court of Claims, created in 1855 to hear and determine all monetary claims against the United States based on a statute, executive branch regulation, or contract. Congress created the court in order to relieve itself of the burden of handling such claims, which it had done since 1789. The statute creating the Court of Claims did not specify whether Congress was exercising its Article III power to create inferior courts, as opposed to its Article I legislative power, but the law specified that the court’s judges were to hold office during good behavior.

In the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909, Congress provided for a U.S. Court of Customs Appeals to hear all appeals from the Board of General Appraisers (later renamed the U.S. Customs Court). The purpose of the new appellate court was to remove the heavy burden of customs appeals from the U.S. circuit courts and U.S. courts of appeals, particularly in New York City, where many such cases originated. Congress provided for the court’s judges to be appointed by the President with Senate confirmation, but did not specify the length of their tenure. In 1929, the court was renamed the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals and given jurisdiction over appeals from the U.S. Patent Office.

At various times in their history, both the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs Appeals became involved in cases that required the Supreme Court to determine whether they were Article III or Article I courts; in other words, whether they were exercising power that was judicial or legislative in nature, and whether their judges possessed the independence made requisite by Article III. Glidden v. Zdanok provided the Court’s final word on that question.

Legal Debates before Glidden

In Gordon v. United States, decided in 1865, the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from the Court of Claims on the ground that the court was exercising legislative, and not judicial, power. Because the judgments of the Court of Claims were subject to revision by the Secretary of the Treasury, the court lacked the ability to enforce them. An order by the Supreme Court affirming a judgment would have been subject to the same executive branch review, intruding upon the separation of powers and impairing judicial independence. In 1866, Congress repealed the statutory provision requiring review by the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Supreme Court began hearing appeals from the Court of Claims. Later cases, however, continued to cast doubt on whether the Court of Claims was an Article III court.

In 1929, the Supreme Court was called upon to decide the constitutional status of the U.S. Court of Customs Appeals in the case of Ex parte Bakelite Corporation. Bakelite petitioned the Supreme Court to prevent the Court of Customs Appeals from hearing an appeal from the U.S. Tariff Commission—a body charged with making findings regarding unfair trade practices and providing recommendations to the President. Article III provided that only an actual “case or controversy” would be cognizable in federal court. Because the Tariff Commission used its findings to advise the executive branch rather than to enter enforceable judgments, Bakelite argued, a proceeding before it was not such a “case or controversy.” The Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, if it were an Article III court exercising judicial power, could not issue an opinion that would be merely advisory, just as the Supreme Court could not issue such an opinion in the Gordon case. At stake once again were concerns over judicial independence and the separation of powers.

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Court of Customs Appeals (by then renamed the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals) was not an Article III court. The court performed functions which, “although mostly quasijudicial, were all susceptible of performance by executive officers.” Congress had created the court in furtherance of its power “to lay and collect duties on imports and to adopt any appropriate means of carrying that power into execution.” Because the Court of Customs Appeals was not exercising the judicial power of the United States, it was irrelevant to the case at hand whether the Tariff Commission proceeding was a “case or controversy” that could be resolved by a federal court exercising judicial power.

Four years later, Williams v. United States presented a similar issue with respect to the Court of Claims. In 1932, Congress passed legislation reducing the salaries of federal judges not protected by the Article III ban on diminution in compensation. The Comptroller General ruled that the Court of Claims was an Article I legislative court, and accordingly subjected its judges to the reduction in pay. Judge Thomas Williams brought suit against the government in his own court, the only forum available, and the Court of Claims certified to the Supreme Court the question of whether it possessed Article III status.

The Court ruled unanimously that the Court of Claims was an Article I legislative court, the judges of which were not protected from diminution of their salaries. In the opinion, Justice George Sutherland noted that matters coming before the Court of Claims were “equally susceptible of legislative or executive determination,” and were therefore “matters in respect of which there is no constitutional right to a judicial remedy.”

In 1953 and 1958 respectively, Congress passed statutes declaring the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals to have been created pursuant to Article III. In the Glidden case, the Supreme Court had the opportunity to rule on the effect of these declarations.

The Case

Glidden involved two separate cases that were consolidated for argument and decision by the Supreme Court. Glidden v. Zdanok was a suit brought in New York state court in 1958 by a group of employees alleging that their employer had breached a collective bargaining agreement. The defendant removed the case to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York and won a ruling that the employees were not entitled to damages, but in 1961 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the decision of the trial court. The appellate court’s opinion was written by Judge J. Warren Madden of the Court of Claims, who was sitting on the Court of Appeals pursuant to a federal statute authorizing the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court to make such temporary assignments.

The other case, Lurk v. United States, involved a conviction for armed robbery in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Presiding over the trial was Judge Joseph R. Jackson, a retired judge of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals who, like Judge Madden in Glidden, was sitting by virtue of a temporary assignment by the Chief Justice. In 1961, the conviction was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The defendants in both cases sought review by the Supreme Court, arguing that judges of the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals should not have been allowed to hear their cases. Because those courts were Article I legislative courts, the defendants argued, their judges lacked the tenure and salary protections of Article III. The defendants claimed that they had been denied the right to have their cases heard by judges possessing the independence of U.S. district and courts of appeals judges.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling

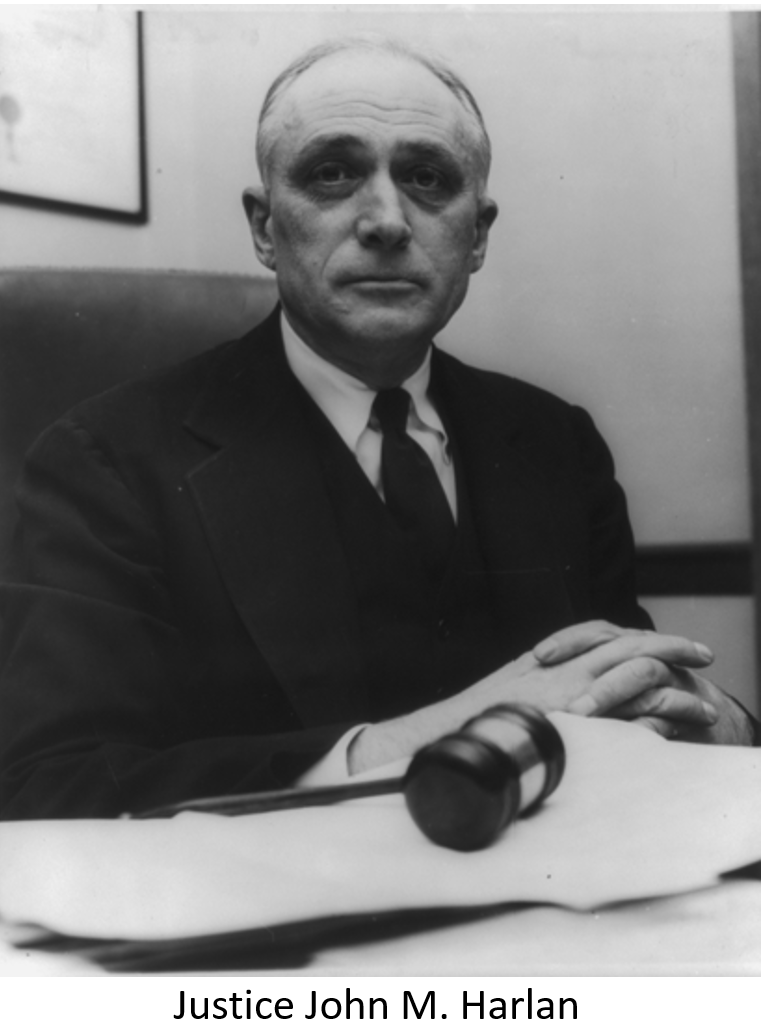

The Supreme Court ruled 5–2 (with two justices not participating in the case) that the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals were Article III courts. Although a majority of the Court agreed on the result, no single opinion expressing the Court’s reasoning won the votes of five justices. The opinion written by Justice John Marshall Harlan and joined by two other justices was a plurality opinion, receiving the most votes while falling short of a majority. A concurring opinion written by Justice Tom Clark and joined by Chief Justice Earl Warren reached the same result while employing somewhat different reasoning.

The challenges to the constitutional status of the two courts gave the Supreme Court the opportunity to revisit its decisions in Bakelite and Williams, in which it had held that both were Article I legislative courts. The plurality noted that the congressional declarations of 1953 and 1958 that both were Article III courts, while entitled to some weight, were not conclusive. Harlan’s opinion pointed out the Court’s responsibility as “the ultimate expositor of the Constitution” to make its own decision regarding the status of the two courts.

At the outset of his plurality opinion in Glidden, Justice Harlan disagreed with an important principle underlying Bakelite and Williams. In those cases, the Court found that if certain business handled by the two courts (appeals from the Tariff Commission heard by the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals and matters referred by Congress heard by the Court of Claims) could have been handled by the legislative or executive branches, that business was inherently nonjudicial and could not be assigned to an Article III court. On the contrary, asserted Harlan, matters susceptible to resolution by other branches could, in some instances, be included within the judicial power. If they were, Congress could create an Article III tribunal to adjudicate them or could delegate them to other officials. The performance of duties that could have been delegated to other branches of government, he concluded, did not automatically deprive a tribunal of Article III status.

Whether a particular court was created under Article III, Harlan stated, “depends basically upon whether its establishing legislation complies with the limitations of that article; whether, in other words, its business is the federal business there specified and its judges and judgments are allowed the independence there expressly or impliedly made requisite.”

The plurality concluded that the early statutory history of the Court of Claims indicated congressional intent to establish the court under Article III. Especially significant was the 1855 act establishing the court, which provided that its judges would be appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate and would have tenure during good behavior. Moreover, when the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from the Court of Claims in 1865 because the Secretary of the Treasury had authority to review the court’s judgments, Congress promptly eliminated that authority, “once again exhibiting its purpose to liberate the Court of Claims from itself and the Executive.” Further evidence of congressional intent was the Tucker Act of 1887, in which Congress gave the court jurisdiction over a range of additional cases, all of which arose “either immediately or potentially under federal law within the meaning of” Article III. Based on the establishing legislation and further statutory developments, Harlan concluded that Congress had intended to design the Court of Claims as an Article III court.

A review of the history of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals led the plurality to the same conclusion. Although Congress had not specified the tenure of the court’s judges when creating the court in 1909, it provided the judges with tenure during good behavior in 1930, immediately after the Supreme Court held in Bakelite that the court had not been created under Article III. Furthermore, the Court of Customs Appeals was at its inception granted jurisdiction over decisions of the Board of General Appraisers, which had formerly been the province of the U.S. circuit courts and circuit courts of appeals, which no one disputed were Article III courts. The plurality therefore found that the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals “fit[] harmoniously into the federal judicial system authorized by Article III.”

Harlan next examined whether both courts were hearing “cases or controversies” as required by Article III. Harlan found that the vast majority of cases heard by the Court of Claims formed “the staple judicial fare of the regular federal courts.” These cases included tax disputes, regulatory challenges, contractual issues, and liability for torts, each of which, wrote Harlan, “is contested, is concrete, and admits of a decree of a sufficiently conclusive character.” “The same may undoubtedly be said,” he went on, “of the customs jurisdiction vested in the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals,” because “[c]ontests over classification and valuation of imported merchandise have long been maintainable in inferior federal courts.” Thus, the bulk of the work conducted by both courts was well within the parameters of the judicial business as defined by Article III.

The concurring opinion reached the same result as the plurality on slightly different grounds. Justice Clark believed that the courts had attained Article III status “upon the clear manifestation of congressional intent” to that effect in 1953 and 1958, particularly in light of the fact that the nonjudicial jurisdiction of both courts had become miniscule. He recommended that the two courts decline to exercise such jurisdiction in the future. Unlike the plurality, Clark did not believe it was necessary to overrule the Bakelite and Williams decisions, which had been issued prior to the congressional declarations, at a time when the problematic aspects of the courts’ jurisdiction had been more significant.

The three justices forming the plurality and the two who concurred in the judgment agreed that both the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals and the Court of Claims were Article III courts and that their judges accordingly possessed constitutionally provided tenure during good behavior and protection against diminution of salary. These judges, therefore, had the requisite degree of independence to sit on the U.S. district court and U.S. court of appeals in the cases at hand. Its holding, the plurality opinion emphasized, did “no more than confer legal recognition upon an independence long exercised in fact.”

In a dissenting opinion joined by Justice Hugo Black, Justice William Douglas explained that he saw no reason to overturn the Court’s Bakelite and Williams precedents. The congressional declarations of 1953 and 1958, he asserted, were of little significance; the status of the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals depended on the nature of their functions, and not on congressional intent. Although Congress did have the power to provide the judges of those courts with tenure during good behavior, a statutory grant of such tenure was not equivalent to that derived from the Constitution.

Aftermath and Legacy

In 1982, Congress abolished both the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals, transferring their judges to a new court, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit, which became the only U.S. court of appeals to be defined by its subject-matter jurisdiction rather than by geographical boundaries, assumed the jurisdiction of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals and the appellate jurisdiction of the Court of Claims. The original jurisdiction of the Court of Claims was transferred to the new U.S. Claims Court, later renamed the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which Congress declared to have been created under Article I.

Although the courts to which the holding in Glidden applied no longer exist, the case underscored the importance of judicial independence by establishing that where Article III adjudication is required, litigants have an enforceable right to have their cases heard by judges possessing the independence Article III protects.

Discussion Questions

- Why was it necessary for the Supreme Court to determine whether or not the Court of Claims and the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals were Article III courts?

- Should the Supreme Court have given conclusive effect to the congressional statutes declaring both courts to have been established under Article III? Why or why not?

- What does it mean for a task to be considered nonjudicial, and why is it problematic for an Article III court to perform such a task?

- What factors did the Supreme Court consider to determine whether the courts had Article III status?