You are here

Tort Claims Against the United States

On December 7, 1776, 6,000 British and Hessian troops landed at Newport, Rhode Island. In response, colonial forces rushed to defend the nearby city of Providence. Having no other barracks available, the American soldiers seized the College Edifice (now known as University Hall) on December 10. The building, which still stands, housed the College of Rhode Island, now known as Brown University. The seizure displaced approximately forty students and forced the college to close its doors. The college building served both as barracks and hospital for American troops until 1780, at which time the college gave notice that students should return for instruction. Almost immediately, however, the government again seized the building, this time as a hospital for French troops.

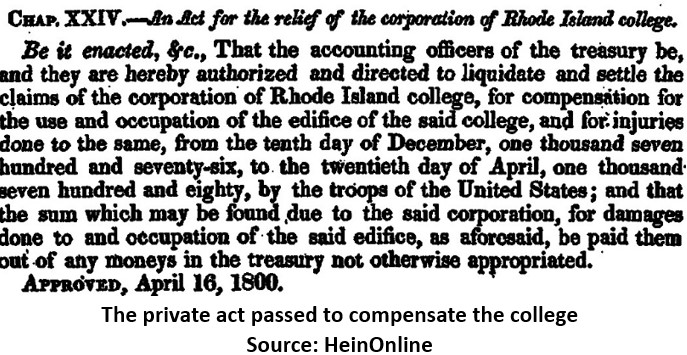

By the time the French vacated the premises in May 1782, the building had suffered serious damage. A committee appointed to survey the building’s condition reported missing doors, hinges, locks, and windows as well as severe structural damage to the walls and roof. The college’s trustees presented a bill to the Confederation Congress in 1782, requesting payment of £1,309 in compensation for the damage. When the U.S. Congress had not paid the college by 1792, the college added interest to the bill, bringing the total to £2,300, or approximately $7,667 (according to a history of Brown University published in 1914). On April 16, 1800, Congress passed a private law—an act for the relief of a specific individual or entity rather than a generally applicable public law—authorizing the Treasury Department to settle the claim. Soon after, the college received payment in the amount of $2,779 for the use of and damage to its building.

The college’s effort to seek compensation from the government for property damage was, in essence, a tort claim. Torts are wrongful acts of a civil rather than criminal nature (not including breach of contract) that cause harm to people or property and for which monetary damages may be awarded. Common examples of torts include trespass, assault, battery, negligence, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and defamation. This spotlight traces the evolution of mechanisms the federal government has employed to handle tort claims brought against the United States, an issue that has always involved competing considerations. On one hand, members of Congress have recognized the fundamental unfairness in failing to compensate victims for injuries caused by government employees acting in an official capacity. On the other, they have sought to limit the financial burden of such claims on the United States as well as to avoid undue judicial scrutiny of governmental operations.

In 1782, the College of Rhode Island had no other choice but to appeal to the Confederation Congress to be compensated for the damage to its building. Even after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the establishment of the federal courts in 1789, there was simply no mechanism by which the college could have successfully sued the federal government. The legal theory of sovereign immunity, widely accepted in America as applied to the federal government, provided that a sovereign government could not be sued without its consent. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes later said while explaining the concept, “there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law upon which the right depends.”

While the origin of the doctrine is uncertain, most scholars have attributed it to English common law. Federal sovereign immunity is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution (although the Eleventh Amendment safeguarded state sovereign immunity in 1795). Article III is ambiguous on the subject, including cases “to which the United States shall be a party” within the federal judicial power. Nevertheless, founders including Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and James Madison expressed their belief in sovereign immunity during the ratification debates, and the Judiciary Act of 1789 granted the circuit courts jurisdiction over cases in which the United States was a plaintiff or petitioner, but not a defendant. The Supreme Court of the United States has consistently maintained the doctrine’s existence, although individual justices have expressed differing views regarding its parameters. Several landmark Supreme Court cases concerned whether a suit against individual government officials could proceed or was in reality a suit against the government and therefore barred by sovereign immunity.

As of 1789, sovereign immunity meant that those bringing claims against the United States had only two avenues for recovery. The first, as illustrated by the case of the College of Rhode Island, was a private law passed by Congress to settle a claim. The second, established by the 1789 act creating the Department of the Treasury, was to submit a claim to that department for a decision by the comptroller. As Congress retained ultimate authority over claims, a claimant dissatisfied with the comptroller’s decision could only petition the legislature for relief. The private law and Treasury systems for handling claims operated side by side.

Over the next several decades, Congress guarded its control over claims closely. Many legislators were wary of allowing judicial resolution of claims, in part because of the requirement in Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution that no money be withdrawn from the treasury other than by congressional appropriation. This concern was exacerbated by statements made by the justices of the Supreme Court in 1792 when they declined to serve as commissioners to handle Revolutionary War veterans’ pension claims. Because their decisions would not be final and enforceable but instead subject to revision by the secretary of war or by Congress, the justices explained, their service as commissioners would be inherently non-judicial and therefore unconstitutional. To solve this problem by giving the courts final authority over claims against the United States, many legislators believed, would be far too great a relinquishment of congressional power and would potentially violate the Constitution’s appropriation clause.

Instead of delegating claims against the government to the federal courts, Congress kept the power in its own hands and those of the Treasury Department. In 1794, the House of Representatives established the Committee of Claims to review monetary claims and report its findings and recommendations back to the full House. During the first three decades of the nineteenth century, Congress created several additional committees to hear specific types of claims, such as those involving land and pensions. American involvement in wars also gave rise to special arrangements. In 1816, for example, Congress authorized the appointment of a commissioner to decide claims for damage to property caused by public use during the War of 1812. Similarly, Congress established the three-member Mexican War Claims Commission in 1849.

By the 1830s, the number of claims addressed to the federal government had increased substantially. Former president John Quincy Adams, elected to the House of Representatives in 1830, complained in a diary entry of 1832 that half of Congress’s time was consumed by private business and that “there is no common rule of justice for any two of the cases decided.” Adams believed that the legislative branch had no place deciding claims, which he viewed as properly the province of the judiciary. By 1838, dissatisfaction with the existing approach led the House to ask the Committee of Claims to investigate the system’s efficacy. The committee’s report indicated that the congressional claims system was breaking down. The number of claims had increased to the point where Congress had the capacity to handle only a small fraction of them, with the result that many valid claims went unaddressed. Congress failed to act on the committee’s report, however, and the situation continued to worsen. In another report of 1848, the committee noted serious deficiencies in the way claims were handled, characterizing the system as “wholly discreditable to any civilized nation.”

For several years following the committee’s scathing report, legislators introduced bills designed to improve the claims system and reduce the burden on Congress, but all failed. Eventually a consensus developed that Congress should create an alternative forum outside of its own halls. In 1855, Congress established the Court of Claims to hear monetary claims against the federal government based on a congressional statute, executive branch regulation, or government contract. Despite its name, the court operated in its first iteration purely as an advisory body, hearing claims in the first instance and reporting to Congress. Congress paid insufficient deference to the court’s advice to allow it to function effectively, however. In the 1860s, the Court of Claims began its evolution to become less like an administrative body and more like a judicial one. In 1863, for example, it was authorized to issue its own decisions, and in 1866, the Supreme Court began to hear appeals from its rulings after Congress eliminated statutory language making Court of Claims judgments dependent on actions by the Treasury Department.

Even as Congress expanded the judicial powers of the Court of Claims over the years, it never vested that court with general jurisdiction over tort claims. The Tucker Act of 1887, for example, significantly increased the court’s jurisdiction, allowing it to hear claims for damages that would, if not for sovereign immunity, have been recoverable in an ordinary court of law, equity, or admiralty, but only “in cases not sounding in tort.”

Instead of waiving sovereign immunity broadly with respect to tort claims, Congress pursued two other avenues to reduce the burden of such claims. The first, beginning during the Civil War, was to permit tort suits in the Court of Claims or the U.S. district courts in specific circumstances. In 1863, Congress enacted a statute permitting the collection of all abandoned or captured property from rebel territory so that it could be put to public use or auctioned. The act allowed those claiming ownership of such property to sue for the proceeds in the Court of Claims within two years of the suppression of the rebellion, provided that they had never given aid or comfort to the Confederacy. A similar statute of 1891 permitted suits in the Court of Claims for property taken or destroyed by Native Americans belonging to a band, tribe, or nation “in amity with the United States.” In 1910, Congress authorized patent owners to seek compensation in the Court of Claims for unlicensed federal government use of their patents. In statutes of 1920 and 1925, Congress gave the U.S. district courts jurisdiction over admiralty and maritime torts where the vessel in question was owned or operated by the United States. Other statutes of a comparable nature followed in future years.

The second element of Congress’s two-pronged strategy for taking some tort claims off its plate was to allow specific types of claims to be resolved by administrative agencies. In 1916, Congress established the U.S. Employees’ Compensation Commission to administer claims arising from the injury or death of a federal employee in the course of their duties. Congress expanded agency remedies in the 1920s, partly as a response to increasing criticism of the doctrine of sovereign immunity. While criticism of the doctrine was not a new phenomenon, it grew sharper in the 1920s as the increasing size and reach of the federal government brought about by the Progressive Era and World War I created more potential tort claims and threatened to overwhelm an already heavily taxed claim system.

Critics of sovereign immunity noted that there was a certain irony in the federal government subjecting Americans to increased regulation while at the same time escaping responsibility for harm caused by government employees. As U.S. Representative Charles Underhill of Massachusetts put it, “It is not right that the Government should impose upon its people, its citizens, requirements, rules, regulations, laws, and penalties which it itself does not observe. It is having a very bad effect on the minds of the people.” Representative Underhill was the chief sponsor of the Small Tort Claims Act of 1922, which authorized the heads of all federal agencies to decide claims for property loss or damage, up to a limit of $1,000, arising from the negligence of a government employee. While the 1922 act required that claims be certified to Congress for payment, some later statutes provided for agencies to make direct payments to claimants.

Most of the administrative tort remedies Congress provided between the 1920s and the 1940s were limited to property damage and had a low cap on the amount of any potential recovery. Examples of such statutes included those authorizing the attorney general, the postmaster general, and the secretary of war to hear claims for property loss or damage caused by activities of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Postal Service, and the Army, respectively. A rare instance in which an administrative remedy went beyond property damage was a 1936 statute authorizing the secretary of state to consider claims regarding the personal injury or death of a non-U.S. national in a foreign country resulting from the negligence of a federal officer or employee, including military personnel. The law was enacted at the request of Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who wished to have the ability to pay such claims brought by Chinese nationals, on the grounds that doing so would improve relations with that nation.

Although Congress enacted several statutes allowing certain tort claims to be resolved judicially or administratively, it continued to pass private laws in some instances in which no other remedy had been provided. Some private laws provided for a direct payment to a claimant, while others waived sovereign immunity for a particular claim so that it could be brought in court. When Congress enacted a private law of the latter type, it frequently specified that the case was to be heard without a jury.

Throughout the 1920s, Representative Underhill urged further tort legislation that would provide for judicial remedies in addition to administrative ones. Thanks in large part to his efforts, Congress passed the Federal Tort Claims Act in 1929, which authorized tort suits against the United States of up to $50,000 for property damage and $7,500 for personal injury. The act received a pocket veto from President Calvin Coolidge, however, because it provided for the comptroller general, rather than the attorney general, to defend the United States in court. Several other tort claim bills were introduced to Congress between the 1920s and the 1940s, but all were unsuccessful. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly criticized the congressional claims system as “slow, expensive, and unfair,” and urged Congress to delegate more claims to the courts.

The version of the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) that became law was passed as part of a broader package of congressional reorganization and reform known as the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946. Despite the controversy surrounding previous legislative attempts at tort claim reform, the FTCA was passed with virtually no debate. The law vested the U.S. district courts with jurisdiction over any claim for monetary damages based on loss of property, personal injury, or death as a result of the negligence, wrongful act, or omission of a federal employee acting within the scope of their duties. All such suits were to be heard without a jury. Appeals from district court judgments could be heard in the U.S. courts of appeals or the Court of Claims. (The act also allowed for the continued administrative resolution of claims under $1,000.) In short, the FTCA constituted a waiver of sovereign immunity in circumstances under which a private person would be liable under the law of the relevant state.

The FTCA also contained a list of exceptions, that is, types of tort claims to which the act’s provisions did not apply. (The FTCA is codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1346(b) and the exceptions at 28 U.S.C. § 2680.) One such exception was for intentional tort claims “arising out of assault, battery, false imprisonment, false arrest, malicious prosecution, abuse of process, libel, slander, misrepresentation, deceit, or interference with contract rights.” In the early 1970s, Supreme Court decisions expanded the scope of some individual officials’ personal liability for intentional torts to deter official wrongdoing and provide compensation to victims who would otherwise lack a remedy, given governmental immunity. In 1974, in response to criticism that it was unfair to make such officials bear tort liability completely on their own, Congress amended the FTCA to allow suits against the government for assault, battery, false arrest, false imprisonment, abuse of process, and malicious prosecution when committed by federal investigative or law enforcement officers.

Members of the military are also barred in most circumstances from bringing tort claims against the United States related to their service. The list of exceptions to the FTCA maintains governmental immunity with respect to claims arising from “combatant activities . . . in time of war.” The Supreme Court has bolstered the government’s immunity from military tort claims by application of the Feres doctrine, named for Feres v. United States (1950). The doctrine provides that the government is not liable for injuries arising from military service or activity incident to such service. Courts have applied the Feres doctrine broadly, precluding recovery for injuries related in virtually any way to a potential claimant’s status as a member of the military. The Supreme Court has explained the doctrine by referencing the disruption that would be caused by judicial involvement in sensitive military affairs as well as the fact that the military maintains its own system for compensating injured service members.

The most significant exclusion from the FTCA is known in shorthand as the “discretionary function” exception. This exception applies whenever a federal employee performs duties pursuant to a statute or regulation (even if the statute or regulation is ultimately found to be invalid) “or based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty.” The exception reflects congressional judgment that governmental decision making should not be hindered by concern over tort liability and that decisions grounded in government policy should not be second-guessed through tort lawsuits.

The Supreme Court first examined the scope of the discretionary function exception in Dalehite v. United States (1953), holding that the exception “includes more than the initiation of programs and activities.” “It also includes determinations,” the Court explained, “made by executives or administrators in establishing plans, specifications, or schedules of operations. Where there is room for policy judgment and decision, there is discretion.” In United States v. Varig Airlines (1984), the Court applied the exception beyond the executive planning function, holding that both the Federal Aviation Administration’s decision to “spot-check” commercial aircraft for compliance with safety standards and the FAA employees’ administration of that policy in certifying the aircraft at issue were discretionary functions within the meaning of the FTCA.

The Court then refined the standard into a two-prong test in Berkovitz v. United States (1988), holding that the exception did not cover every act arising from an agency’s regulatory program, but only those that involved an element of judgment or choice and were based on public policy considerations. In Berkovitz, the Court ruled that the exception did not warrant the immediate dismissal of a lawsuit against the National Institutes of Health’s Division of Biologic Standards and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration over the approval of, and release to the public of a certain batch of, a polio vaccine. The plaintiff’s allegations, taken as true for the purposes of a summary judgment motion, were that the two agencies had violated their own mandatory policies in the licensing and release of the vaccine. The defendants’ alleged actions, therefore, did not constitute permissible exercises of discretion that would except the lawsuit from the FTCA.

The system for handling claims against the federal government for damage to people and property has evolved since the nation’s founding from one controlled completely by Congress to one that is primarily judicial. The size and reach of the federal government, the number of potential claims, and the other work occupying legislators’ time all continued to grow until a predominantly congressional system was no longer feasible. Legislators also recognized that the federal courts were the entities best equipped to decide claims that were identical in substance to work that had always been considered judicial in nature. The FTCA was meant to strike a balance between the competing considerations that have always played a role in the formulation of federal tort claim policy. The act aims to provide those harmed by the government their day in court while avoiding undue judicial hinderance of the discretionary decision making required for effective governance.

Jake Kobrick, Associate Historian

For more information, contact history@fjc.gov

Related FJC Resources:

Cases that Shaped the Federal Courts: Glidden v. Zdanok, Gordon v. United States, Hayburn’s Case

Jurisdiction of the Federal Courts: Civil, United States as a Party

Further Reading:

Contino, Michael D. and Andreas Kuersten. “The Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA): A Legal Overview.” Congressional Research Service R45732 (2023).

Gottlieb, Irvin M. “Federal Legislation: Tort Claims Against the United States.” Georgetown Law Journal 30, no. 5 (March 1942): 462–472.

Hankins, Grover Glenn. “The Federal Tort Claims Act: A Smooth Stone for the Sling.” Gonzaga Law Review 31, no. 1 (1995–1996): 27–68.

Holtzoff, Alexander. “The Handling of Tort Claims Against the Federal Government.” Law and Contemporary Problems 9, no. 2 (Spring 1942): 311–326.

McGuire, O. R. “Tort Claims Against the United States.” Georgetown Law Journal 19, no. 2 (January 1931): 133–147.

McMahan, Jennifer L. and Mimi Vollstedt. “Researching the Legislative History of the Federal Tort Claims Act.” United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 59, no. 1 (January 2011): 52–57.

Shimomura, Floyd D. “The History of Claims Against the United States: The Evolution from a Legislative Toward a Judicial Model of Payment.” Louisiana Law Review 45, no. 3 (January 1985): 625–700.

Sisk, Gregory C. “A Primer on the Doctrine of Federal Sovereign Immunity.” Oklahoma Law Review 58, no. 3 (Fall 2005): 439–468.

____________. “The Tapestry Unravels: Statutory Waivers of Sovereign Immunity and Money Claims Against the United States.” George Washington Law Review 71, no. 4–5 (September/October 2003): 602–707.

Wiecek, William M. “The Origin of the United States Court of Claims.” Administrative Law Review 20, no. 3 (April 1968): 387–406.

This Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to “conduct, coordinate, and encourage programs relating to the history of the judicial branch of the United States government.” While the Center regards the content as responsible and valuable, these materials do not reflect policy or recommendations of the Board of the Federal Judicial Center.