You are here

The Codification of Federal Statutes on the Judiciary

Note: This spotlight was adapted from a 2021 Twitter thread by the same author.

As many legal researchers know, federal statutes relating to the judiciary are found in Title 28 of the United States Code. Title 28 constitutes a large body of law about the operation of the federal judiciary, covering topics such as the number of judgeships authorized for each court, the places courts may meet, the parameters of the courts’ jurisdiction, the officers and other employees who serve the courts, general procedural requirements, and requirements for particular proceedings such as petitions for habeas corpus or cases before the U.S. Court of Federal Claims.

The title consists of six parts, each of which is divided into multiple chapters which are themselves divided into sections. In legal and scholarly documents, only the title and section of a law are cited. The provision for diversity jurisdiction in the U.S. district courts, for example, is given as 28 U.S.C. §1332. Having federal laws about the courts collected in one place, neatly divided by subtopic and numbered, makes the task of locating a particular provision relatively straightforward. Judicial statutes have not always been so well organized or easy to find, however. This spotlight details some of the most significant developments in the long quest to improve the organization and dissemination of these federal statutes to provide clarity on the state of the law.

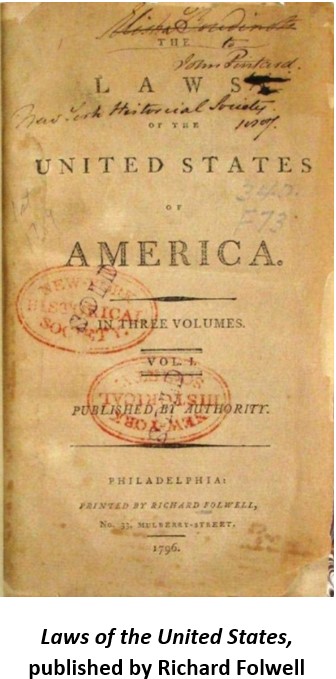

When Congress passed the first statutes under the Constitution, including the Judiciary Act of 1789 that established the lower federal courts, it sent the laws to the secretary of state with the instruction to publish them in at least three newspapers and to send copies to members of Congress and state authorities. In 1795, Congress for the first time passed a law authorizing the secretary of state to have a full set of federal laws printed, including an index. The Laws of the United States of America, compiled by Zephaniah Swift and published by Richard Folwell, consisted of three volumes bearing a publication date of 1796 but including laws from 1789 to March of 1797. Other publishers added volumes numbered four through twelve, which covered laws up to 1815.

In 1814, Congress authorized the secretary of state to contract with John Bioren and W. John Duane for 1,000 copies of a set of U.S. laws and treaties. The Bioren and Duane edition was distinct from that begun by Folwell because it followed a specific plan established by Secretary of State Richard Rush. Rush’s plan included, for example, publishing the text of obsolete or repealed statutes with references to the statutes affecting them. This edition was published as a five-volume set in 1815; other publishers subsequently extended the series to ten volumes.

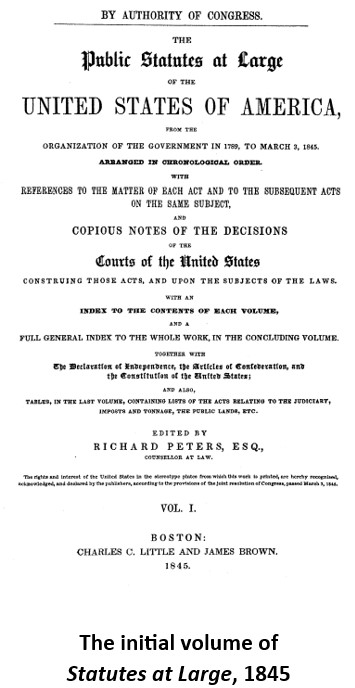

The series begun by Bioren and Duane continued until 1845, at which time Congress authorized a new publication that proved to be far more enduring than its predecessors. Boston publishers Little & Brown were authorized to begin printing the Public Statutes at Large, to contain, in chronological order, all public acts, private acts, and treaties since 1789. The first five volumes of Statutes at Large, covering public acts 1789–1845, were published by 1846. Volumes 6–8 contained all private acts, Indian treaties, and foreign treaties. In 1846, Congress declared the Little & Brown edition “competent evidence” of federal law in all federal and state courts “without any further proof or authentication.” This declaration made these volumes prima facie evidence, that is, evidence sufficient to establish a fact in court while remaining rebuttable by conflicting evidence. While an original act of Congress would prevail over Statutes at Large in the event of a discrepancy, this was the first time that any legal weight had been accorded to a published compilation of statutes.

Little & Brown continued to publish Statutes at Large through volume 17, which covered laws up to March 1873. Thereafter, the U.S. Government Printing Office took over publication, which continues to the present day. Once Statutes at Large became a government publication, Congress gave future volumes greater significance by declaring them to be “legal evidence” of the laws contained therein and therefore no longer rebuttable in court. Each volume covered one Congress beginning with volume 13, which included laws from the Thirty-Eighth Congress (1863–1865). In 1937, volumes began to appear annually with occasional exceptions. Volume 131, the most recent to be published as of this writing, contains laws passed in 2017, with more recent laws available online.

While Statutes at Large was a valuable resource, nineteenth-century legal researchers were continuously plagued by the lack of a collection of all statutes organized by subject (although laws had been compiled for a handful of subjects, such as public lands, customs duties, and the military). Lawyers and judges frequently had to search multiple volumes to find all relevant statutes on an issue, some of which had likely been repealed, superseded, or amended, making research confusing. In 1866, Congress attempted to solve this problem by authorizing the president to appoint three commissioners to “revise, simplify, arrange, and consolidate all statutes of the United States.” Congress, however, rejected the commission’s 1872 report on the grounds that the commission had altered statutory language too much.

Congress’s next step was to authorize a joint congressional committee to hire an individual to revise and consolidate the statutes. The committee gave the job to constitutional lawyer Thomas Jefferson Durant, whose report became the Revised Statutes of the United States, published in 1875. Congress granted the Revised Statutes official status by enacting them collectively into positive law (a term connoting man-made law as opposed to natural law and typically used to refer to statutes). This made the Revised Statutes legal evidence, rather than merely prima facie evidence, of the law. The compilation contained all laws “general and permanent in their nature” as of December 1, 1873, and expressly repealed all laws enacted prior to that date that were embraced by the revision, thereby making most of Statutes at Large obsolete. (One can find scholarly references to this compilation as the Revised Statutes of 1873, 1874, and 1875, as various authors have used the year of the most recent statutes included, the year of enactment, and the year of publication.)

The Revised Statutes divided the laws into seventy-four titles, with laws concerning the judiciary forming Title XIII. For the first time, laws regarding the operation of the federal courts were organized and collected in one place. The twenty-one chapters of Title XIII covered topics such as the composition of judicial districts and circuits, the meeting times and places of district and circuit courts, jurisdiction, evidence, juries, and procedure. The Revised Statutes were criticized as containing a large number of errors, however, and the 1875 volume had an appendix of corrections already attached. A second edition of the Revised Statutes was published in 1878, but this new edition, containing statutes up to January 1, 1878, was not enacted into positive law. In the event of a discrepancy, therefore, Statutes at Large would take precedence over the Revised Statutes with respect to an act passed by Congress after December 1, 1873. Supplements to the Revised Statutes were published in later years and also remained unenacted.

In 1897, Congress created another commission, later named the Commission to Revise the Laws of the United States, charged with revising and codifying federal criminal laws. The commission’s mandate was expanded to include judicial statutes in 1899 and then to encompass all statutes of a general and permanent nature in 1901. The commission submitted several reports to Congress, but in 1910 Congress abandoned the idea of codifying all federal statutes and disbanded the commission.

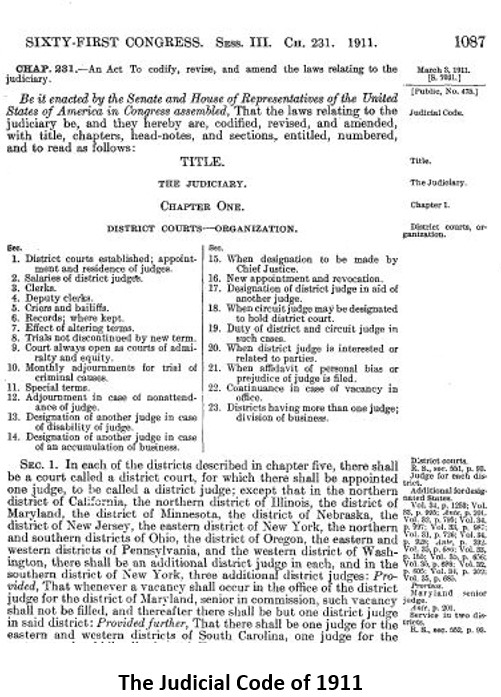

The criminal code produced by the commission was enacted into law in 1909, the judicial statutes were enacted as the Judicial Code of 1911, and the rest of the commission’s work was not enacted. The 1911 Judicial Code expressly repealed portions of the Revised Statutes and repealed all prior acts or parts of acts that were embraced by the code’s provisions. It contained 301 sections divided into fourteen chapters. Most significantly, the 1911 Code abolished the U.S. circuit courts, which had been the nation’s main trial courts since 1789 and had appellate jurisdiction until the creation of U.S. courts of appeals in 1891. Upon their abolition, the jurisdiction of the circuit courts was transferred to the U.S. district courts.

Some members of Congress had not given up on the idea of preparing a codification of all federal statutes. Edward Little, the chair of the House Committee on the Revision of the Laws of the United States, led the effort, and in 1919 work on what eventually became the U.S. Code began. Several versions of the compilation were introduced to Congress during the Sixty-Sixth, Sixty-Seventh, and Sixty-Eighth Congresses all of which passed the House but failed to pass the Senate because they were believed to contain too many errors. In 1925, the work was turned over to the West Publishing Company and Edward Thompson Company, which already published private editions of annotated statutes. The companies built on the work that had already been done by the commission of 1897 as well as the House committee.

Congress approved the U.S. Code in 1926 but did not enact it into law. The Code was originally intended to repeal all prior laws, but the bill as passed provided that the Code neither repealed any law nor created any new law and was only prima facie evidence of the law. As was true of other compilations constituting evidence of the law but not law themselves, the language of the Code could be rebutted in court in case of any discrepancy. If a code provision were found to contradict an act found in Statutes at Large, therefore, the latter would prevail in court.

The 1926 Code contained fifty titles with the statutes relating to the judiciary contained in Title 28. The sections within Title 28 cross-referenced the sections of the Judicial Code of 1911 where appropriate. Congress provided in 1929 for new editions of the U.S. Code to be printed not more often than every five years. A new edition was published in 1934 and then every six years thereafter, most recently in 2018, with another due to be published in 2024. Annual supplements are published in the years between new editions.

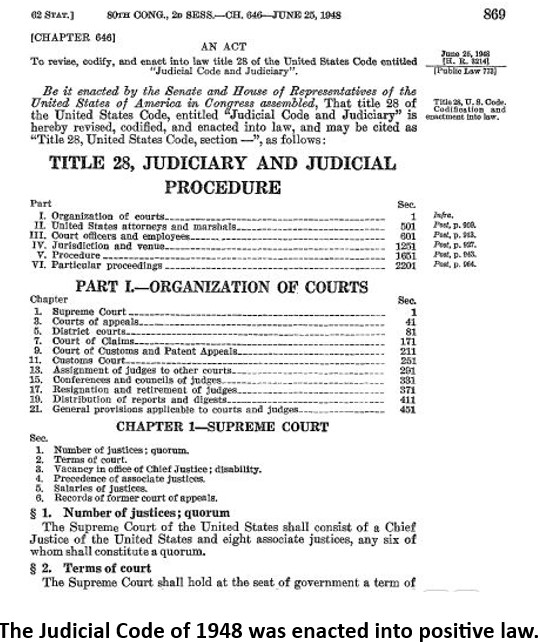

Because of the number of errors discovered after the Revised Statutes were enacted into law, Congress elected to take a more cautious, title-by-title approach to enacting the U.S. Code, and seven titles, including Title 28, were enacted individually in 1947 and 1948. Congress began the effort to revamp Title 28 to correct errors, remedy omissions, and improve organization in 1944 and enacted the title into law on June 25, 1948. The Judicial Code of 1948, as the revised body of laws is sometimes called, created the basic structure of Title 28 of the U.S. Code that exists today.

The 1948 revision made some substantive changes to the law, including provisions related to jurisdiction and venue. One such provision expanded diversity jurisdiction (that is, jurisdiction over suits between citizens of different states) by including the District of Columbia and territories within the definition of “state.” The 1948 code also formally added the District of Columbia as a judicial district and circuit and regularized the names of its courts to make them consistent with others. Some changes were administrative in nature, such as the creation of the chief judge position on the U.S. district courts and U.S. courts of appeals and the move from setting the terms of the district courts by statute to determining them by order of each court. Other changes were aimed at modernizing and simplifying language. For example, district attorneys were renamed U.S. attorneys, the U.S. circuit courts of appeals were renamed the U.S. courts of appeals, and the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges became the Judicial Conference of the United States.

As of this writing, Congress has enacted twenty-seven titles of the U.S. Code into positive law. Roughly half of the Code, therefore, is nonrebuttable legal evidence of the law, while the other half remains prima facie evidence of the law that can be rebutted by a contradictory provision in Statutes at Large. Congress must take account of the different statuses of various parts of the Code when it amends existing statutes. When amending a provision of a positive law title such as Title 28, Congress may enact a statute that simply changes the language of the relevant sections of that title. When amending a title that has not been enacted into law, however, Congress must amend not the Code but the original statute on which the relevant code provisions are based.

If Congress passes a new law but does not state the title of the U.S. Code into which it is to be placed, the Office of Law Revision Council (OLRC) (an independent office within the House of Representatives responsible for maintaining the U.S. Code) will make that determination. If the OLRC places the new law into a title that has been enacted into law, the law will appear in a statutory note rather than the main text. One such example is the Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991. Because the OLRC decided that the law belonged in Title 28, a positive law title, but the law did not expressly modify or add any code section, it was placed in a note under 28 U.S.C. §1350 (alien’s action for tort). If the OLRC determines that a new statute belongs in a title that has not been enacted into law, it will typically place the law into a new code section but in some instances will make an editorial decision to place it in a note instead. Because of this quirk of the legislative process, some researchers are unaware that statutory law can be found in the notes of the U.S. Code as well as in the sections.

As this spotlight has shown, the organization and dissemination of federal statutes regarding the judiciary has evolved significantly since the days of the Early Republic, albeit not without significant difficulty along the way. As the number of statutes grew, the laws were consolidated, organized, refined, and ultimately enacted into law as a single unit known as Title 28. The effort to harmonize the entire U.S. Code by enacting all of its titles into positive law continues. Once this task has been completed, legal researchers will finally be able to access all of permanent U.S. statutory law in one place without concern for potential contradictions in other sources.

Jake Kobrick, Associate Historian

For more information, contact history@fjc.gov

Further Reading:

Bethell, Edgar E., and Herschel Friday. “The Federal Judicial Code of 1948.” Arkansas Law Review 3, no. 2 (Spring 1949): 146–159.

Brown, Henry B. “The New Federal Judicial Code.” Central Law Journal 73 (October 1911): 275–281.

Cross, Jesse M. “Where is Statutory Law?” Cornell Law Review 108, no. 5 (July 2023): 1041–1116.

Dwan, Ralph H., and Ernest R. Feidler. “The Federal Statutes–Their History and Use.” Minnesota Law Review 22, no. 7 (June 1938): 1008–1029.

Nevers, Shawn G., and Julie Graves Krishnaswami. “The Shadow Code: Statutory Notes in the United States Code.” Law Library Journal 112, no. 2 (Spring 2020): 213–256.

Surrency, Erwin C. “The Publication of Federal Laws: A Short History.” Law Library Journal 79, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 469–484.

Tress, Will. “Lost Laws: What We Can’t Find in the United States Code.” Golden Gate University Law Review 40, no. 2 (Winter 2010): 129–164.

Whishner, Mary. “The United States Code, Prima Facie Evidence, and Positive Law.” Law Library Journal 101, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 545–556.

This Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to “conduct, coordinate, and encourage programs relating to the history of the judicial branch of the United States government.” While the Center regards the content as responsible and valuable, these materials do not reflect policy or recommendations of the Board of the Federal Judicial Center.