You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

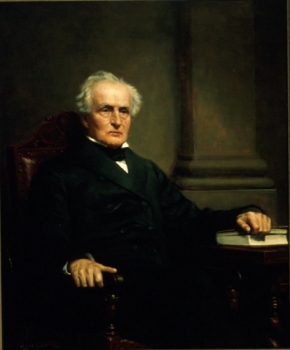

Associate Justice William Strong, United States v. Given (1873)

United States v. Given, 25 F. Cas. 1324 (C.C.D. Del. 1873) (No. 15,210) [Third Circuit]

In Given, a tax collector for the state of Delaware was convicted under the Enforcement Act of 1870, a statute intended primarily to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment. The second section of the act prohibited any state or local official from denying a person the opportunity—based on that person’s race, color, or previous condition of servitude—to perform an act needed to qualify to vote. In Delaware, a resident was required to pay a county tax in order to vote. The defendant thus had the power to disqualify a potential voter by, for example, failing to collect the tax or reporting falsely that the tax had not been paid.

After conviction, the defendant moved to arrest the judgment on the grounds that the Enforcement Act was unconstitutional. Justice Strong began his analysis by stating that the Fifteenth Amendment had conferred positive rights upon the people of the United States, a major point of contention in the debate over whether individuals could be prosecuted for civil rights violations. “It is true the amendment is in form a prohibition upon the United States and upon the states, but it is not the less on that account an assertion of a constitutional right belonging to citizens as such. Surely it cannot be maintained that it conferred no rights upon persons,” he wrote.

The existence of a constitutional right, Strong noted, implied congressional power to enforce that right. In this case, however, the power of Congress was made explicit by the second section of the Fifteenth Amendment, which authorized Congress to adopt “appropriate legislation” to enforce its terms. If that authorization meant only that Congress could pass legislation invalidating racially discriminatory state voting laws, he reasoned, the second section “would make superfluous and unmeaning all that was accomplished by the first section.” Instead, Congress had anticipated that the amendment, which “was regarded with great disfavor” by many, might be evaded not by state laws, “but by private persons and ministerial officers, by assessors, collectors, boards of registration, or election officers.” If this type of discrimination were not outlawed, he concluded, the rights granted by the amendment would be left “without full and adequate protection.” The second section of the Enforcement Act, under which the defendant had been convicted, was therefore constitutional.

What was remarkable about Strong’s opinion was the expansive reading he gave to the Reconstruction Amendments at a time when the federal judiciary was about to begin heading in the opposite direction, with his help. He described the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments as introducing “great changes” with respect to federal power to enforce civil rights. “Those amendments have left nothing to the comity of the states affecting the subjects of their provisions,” he continued. “They manifestly intended to secure the right guaranteed by them against any infringement from any quarter.” Ironically, only weeks later, Strong was part of the Supreme Court majority that decided the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873). One of the most consequential decisions in the Court’s history, the opinion blunted the federal government’s ability to enforce the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Strong’s reasons for changing his position are unclear. The ruling marked the beginning of an era in which the Court continued to narrow the scope of federal enforcement of civil rights under the Reconstruction Amendments.