You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

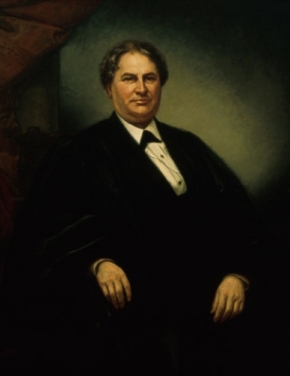

Associate Justice Samuel Freeman Miller, Wisconsin v. Duluth (1872)

Wisconsin v. Duluth, 30 F. Cas. 382 (C.C.D. Minn. 1872) (No. 17,902) [Eighth Circuit]

The state of Wisconsin sued the city of Duluth, Minnesota, seeking an injunction to prevent it from maintaining a canal the city had built at Minnesota Point. The canal diverted the current of the St. Louis River, which formed a natural boundary between the two states, allegedly injuring Wisconsin’s interests in the river for navigation and commerce. The defendant sought to have the case dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, asserting that a state could not sue in a U.S. circuit court.

Justice Miller first noted that Article III of the Constitution extended the judicial power to suits in which a state was a party. That article also vested the Supreme Court with original jurisdiction over such suits, however, raising the question of whether that jurisdiction was exclusive or could be exercised concurrently by the circuit courts. Miller reasoned that if the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction over a case, it could not exercise appellate jurisdiction over the same case. If a state brought a suit in the circuit court, therefore, no appeal or writ of error could be taken to the Supreme Court. “This would be an anomaly in our jurisprudence, which stands alone,” he wrote, “and it weighs very heavily against” construing the law to allow circuit court jurisdiction over such cases.

Miller then turned to the language of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the eleventh section of which set out the circuit court’s jurisdiction when based on the identity of the parties. That section referenced suits “between a citizen of the State where the suit is brought, and a citizen of another State,” but made no mention of suits brought by a state itself. To consider a state merely an aggregation of its citizens, wrote Miller, “cannot be maintained upon any sound view of the constitution.” Moreover, the thirteenth section of the 1789 act clearly distinguished between states and citizens, such as in the clause denying the Supreme Court original jurisdiction over cases between a state and its citizens.

If the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction over cases to which a state was a party was not exclusive, concluded Miller, concurrent jurisdiction lay in the state rather than the federal courts. If Congress could confer concurrent jurisdiction on the U.S. circuit courts, it was “a sufficient answer to say that it has not done it.” Miller therefore dismissed the case. Wisconsin later brought its suit in the Supreme Court. In an 1877 opinion written by Miller, the Court ruled that it had no authority to direct or forbid congressionally authorized work on a harbor, including the construction of the canal.

In Ames v. Kansas (1884), the Court ruled that a corporation sued by a state could remove the suit to federal court under the terms of the Jurisdiction and Removal Act of 1875. The 1875 act provided for the removal of any civil suit brought in a state court arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States. The statute, the Court noted, “makes no exception of suits to which a State is a party.” Chief Justice Morrison Waite, who wrote the Court’s opinion, pointed out that the jurisdiction provided by the 1875 act had not existed when Justice Miller decided Wisconsin v. Duluth on circuit.