You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

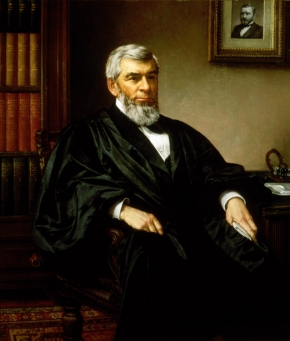

Chief Justice Morrison Remick Waite, United States v. Butler (1877)

United States v. Butler, 25 F. Cas. 213 (C.C.D.S.C. 1877) (No. 14,700) [Fourth Circuit]

In September 1876, a racial massacre took place in Ellenton, South Carolina. The bloodshed was possibly on par with the Colfax Massacre of 1874 in Louisiana (the subject of United States v. Cruikshank (1876)). The week-long “race riot” began with the killing of an African American man in retaliation for an alleged assault upon a white woman and her son. It then escalated, with armed white men pouring into the area with the aim of killing as many African American men as possible. The exact death toll is not known but might have reached 125 before federal troops arrived to stop the violence.

The massacre was motivated at least in part by a desire to intimidate black voters leading up to the 1876 election, in which the Democrats ousted the state’s Reconstruction government and reestablished white supremacist rule. Some of the perpetrators were charged under the Enforcement Act of 1870 and the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 with conspiring to use force to prevent David Bush, an African American man who was murdered, from giving his support to a black candidate for the U.S. Congress, to injure him as a result of his giving such support, to prevent him from voting in the 1876 election because of his race, and to prevent him from voting for a particular candidate in that election for the same reason.

Chief Justice Waite, sitting with U.S. Circuit Judge Hugh Lennox Bond, upheld these four counts of the indictment while dismissing one other. The fact that these counts survived was significant, because whether the federal government could prosecute individuals for violating Fifteenth Amendment rights was a major point of contention. Waite and Bond implicitly accepted the theory Justice Joseph Bradley espoused in his circuit court opinion in Cruikshank, that Congress had the power to protect the right to be exempt from racial discrimination with respect to voting “not only as against the unfriendly operation of state laws, but against outrage, violence, and combinations on the part of individuals, irrespective of the state laws.”

The report of the case recounted the facts of the brutal massacre in great detail. As in Cruikshank, however, the perpetrators went free. One was acquitted, and the jury could not agree on the others, resulting in a mistrial. One factor that might have made conviction more difficult was Waite’s instruction to the jury that to convict, they must find that the defendants intended to interfere with Bush’s voting rights “on account of his race or color, without regard to his political belief or association.” Some jurors may have voted to acquit because they did not believe the prosecution had proved that Bush’s race, rather than his support for the Republican Party or a particular candidate, was the defendants’ sole or predominant motive.