You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

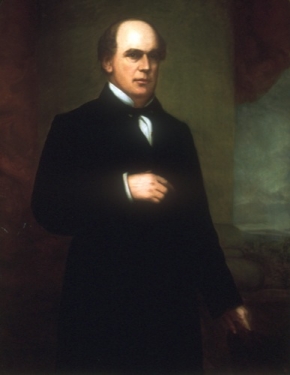

Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, Shortridge v. Macon (1867)

Shortridge v. Macon, 22 F. Cas. 20 (C.C.D.N.C. 1867) (No. 12,812) [Fourth Circuit]

In Shortridge, Chief Justice Chase was called upon to rule on the validity of laws passed by the Confederate government during the Civil War. The defendant, a citizen of North Carolina, owed money to the plaintiff, a citizen of Pennsylvania. Laws enacted by the Confederacy in 1861 and 1862 required the defendant to pay the amount due to a receiver appointed by that government. After the war, the plaintiff sued to recover the debt, and the defendant asserted that the coerced payment to the receiver had discharged him of his obligation to the plaintiff.

The defendant argued that the United States had afforded the Confederate armed forces the rights of a belligerent during the war, treating it as a foreign government and thus enabling it to seize the property of U.S. citizens within its borders. Chase rejected this argument, holding that North Carolina’s secession and joining of the Confederacy “did not effect, even for a moment, the separation of North Carolina from the Union.” These actions were illegal—and, in fact, constituted treason by levying war against the United States—and could not relieve the state or its citizens of any obligations under U.S. law. The executive and legislative branches had decided for policy reasons to treat the Confederacy as a belligerent, wrote Chase, and that decision “established no rights except during war.” The United States government had never renounced its constitutional authority over North Carolina and had never recognized the Confederacy as a legitimate government.

Arguing by analogy, the defendant also asserted that American courts had approved of the confiscation of the property of nonresident British subjects after the Revolutionary War. The obvious difference, Chase pointed out, was that the Americans had won that war, severing their connection with Great Britain and establishing their own government. The Revolution could have served as a proper analogy only had Americans lost the war and then had their confiscations of British property confirmed by British courts.

“Those who engage in rebellion must consider the consequences,” Chase concluded. “If they succeed, rebellion becomes revolution, and the new government will justify its founders. If they fail, all their acts hostile to the rightful government are violations of law, and originate no rights which can be recognized by the courts of the nation whose authority and existence have been alike assailed.” He ordered the defendant to pay the debt in full, including interest. The Supreme Court ruled similarly in Texas v. White (1869), holding that states did not have the right to secede from the Union and that consequently Texas had remained a state throughout the Civil War.