You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

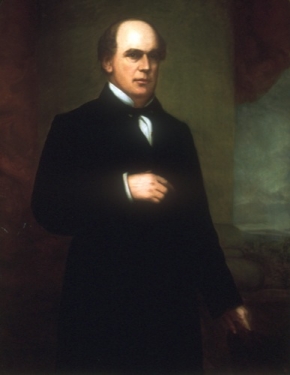

Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, In re Turner (1867)

In re Turner, 24 F. Cas. 337 (C.C.D. Md. 1867) (No. 14,247) [Fourth Circuit]

The Maryland Constitution of 1864, which went into effect on November 1 of that year, abolished slavery within the state’s borders. Planters, wishing to maintain a system that resembled slavery to the greatest possible extent, took advantage of the state’s racially discriminatory laws (known as the “Black Code”) to force black children into apprenticeships, usually with their former masters. Parents of the apprenticed children brought suits in both state and federal courts seeking their release and were successful in some cases.

The case of Elizabeth Turner, who was indentured two days after the abolition of slavery, came before Chief Justice Chase while riding circuit in Baltimore. Turner’s former master, Philemon Hambleton, made no argument because he did not wish to spend any money on the case. Chase lamented that he would have to decide the case without the benefit of argument on both sides.

Explaining that he was pressed for time, Chase issued a very short opinion that nevertheless had important consequences for Maryland’s newly freed people. Examining the state’s apprenticeship laws, he noted that they were severely unequal. Black apprentices were not entitled to any education, while white apprentices were; black apprentices could be transferred to another person against their will, while white apprentices could not be; and the law described the authority of masters of black apprentices as “property and interest” but made no such designation for white apprentices.

Chase found Turner’s apprenticeship illegal on the grounds that it violated the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition of involuntary servitude as well as the guarantee to all citizens of the “full and equal benefit of all laws” contained in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (soon after incorporated by the Fourteenth Amendment as the Equal Protection Clause). In accordance with the 1866 act, Chase declared that “[c]olored persons equally with white persons are citizens of the United States.” He then ordered Turner’s release.

Chase’s opinion was immediately recognized as groundbreaking, not only for its invalidation of Maryland’s apprenticeship law, but also for its expansive interpretation of the Thirteenth Amendment as bestowing a positive right to freedom on all citizens. The Freedman’s Bureau in Maryland immediately took Chase’s decision in Turner to U.S. District Judge William Giles, who had recently denied a writ of habeas corpus in a similar case. Giles reversed his decision and issued a new opinion. Bureau agents then printed Chase’s and Giles’s decisions as a circular and distributed it to those holding black children as apprentices to inform them that they were doing so illegally. Within a year, Bureau lawyers had returned 110 children to their parents. The practice of involuntary apprenticeship ended soon afterwards.