You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

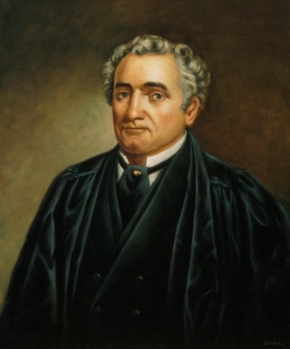

Associate Justice John Catron, In re Klein (1843)

In re Klein, 14 F. Cas. 716 (C.C.D. Mo. 1843) (No. 7,865) [Eighth Circuit]

In 1841, Congress enacted a national bankruptcy statute pursuant to the Constitution’s grant of authority in Article I, section 8, to make “uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States.” In September 1842, U.S. District Judge Robert Wells of Missouri denied Klein’s petition to be discharged from his debts on the grounds that the bankruptcy act was unconstitutional. Several other bankruptcy cases on Wells’s docket appeared to be destined for the same fate.

Undoubtedly worried about losing a significant source of business, members of the St. Louis bar wanted to secure a Supreme Court ruling that the bankruptcy law was constitutional as soon as possible. Under an 1802 statute, a circuit court could ask the Supreme Court to decide a point of law on which the circuit court judges—a U.S. district judge and a Supreme Court justice—were divided in opinion. Knowing that the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Missouri would not hear Klein’s appeal until its next session in 1843, the attorneys instead requested assistance from the federal courts in Kentucky, which began their sessions in November 1842.

U.S. District Judge Thomas Monroe of Kentucky had a bankruptcy case, Nelson v. Carland, on his docket. A provision of the bankruptcy act permitted a district judge to send any question to the circuit court for decision, and Monroe did so with respect to the act’s constitutionality. Sitting on the circuit court, Monroe and Justice Catron then submitted a certificate of division on the question to the Supreme Court.

At its January 1843 term, the Supreme Court dismissed Nelson for lack of jurisdiction. The Court ruled that a district judge was not permitted to sit on the circuit court when it was deciding a bankruptcy question it had received from the district court. The Court’s holding, by mandating that the Supreme Court justice riding circuit decide the issue unilaterally, made a division of opinion among circuit court judges impossible. The justice’s opinion would therefore be final, as the question could not reach the Supreme Court.

Justice Catron dissented in Nelson, arguing that the Court possessed jurisdiction over questions certified from the circuit courts in bankruptcy cases. The Bankruptcy Act of 1841 did not explicitly prohibit district judges from hearing bankruptcy matters in circuit courts, and Catron did not believe that Congress intended to bar them. Because the Supreme Court lacked appellate jurisdiction over bankruptcy cases, a finding that the Court could not hear certified questions in these cases meant that no bankruptcy case could reach the Court. Depriving the Court of any ability to rule on bankruptcy cases was bad policy, Catron thought, particularly in light of the lower courts’ many conflicting interpretations of what was meant to be a uniform law.

Denied an opportunity to decide the constitutionality of the 1841 act in Nelson, Catron had his chance when the appeal of Judge Wells’s dismissal of Klein—the case that had provided the real impetus for the question being brought to the Supreme Court—came before him at the spring 1843 term of the Missouri circuit court. Catron noted that he would not go into detail about Wells’s reasons for deeming the law unconstitutional, because he had described the district judge’s opinion at length in his Nelson dissent. Wells’s objections to the law were multifaceted but boiled down to his belief that the law benefited only debtors at the expense of creditors, which was inconsistent with the English bankruptcy laws known by the framers of the Constitution. Wells also thought the bankruptcy law violated the Contracts Clause, which prohibited the states from making any law impairing the obligation of contracts.

Catron disagreed with Wells’s reasoning, reversing his judgment and holding the bankruptcy statute to be constitutional. The power of Congress, Catron ruled, “extends to all cases where the law causes to be distributed the property of the debtor among his creditors.” Any legislation in this field, up to and including that providing for the discharge of debtors from their debts, was “in the competency and discretion of Congress.” The wisdom of the policy embodied by the act, he continued, was not a matter for the courts to decide. Catron’s ruling applied only to bankruptcy cases in the Eighth Circuit that had already commenced, however. Congress had repealed the unpopular bankruptcy act in March 1843, so no new cases could be filed.