You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

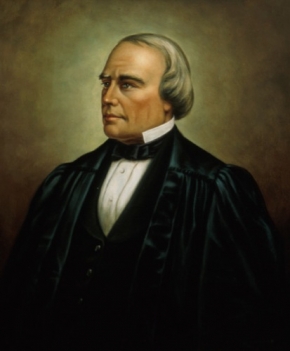

Associate Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Greene v. Briggs (1852)

Greene v. Briggs, 10 F. Cas. 1135 (C.C.D.R.I. 1852) (No. 5,764) [First Circuit]

In 1852, the state of Rhode Island passed a statute called “An act for the suppression of drinking-houses and tippling shops” aimed at the illegal sale of liquor. According to the act, anyone who suspected that liquor was being held for illegal sale could make a complaint to a justice of the peace. The complainant was required to identify the place where the liquor was held but did not have to name any particular person in the complaint. The justice of the peace would then issue a warrant to the sheriff, who was authorized to search for and seize the liquor in question.

After public notice, the owner of the seized liquor could appear before the justice of the peace and attempt to recover it. If the justice ruled against the owner, the liquor would be forfeit and the owner would be fined $20 or imprisoned for thirty days for failure to pay the fine. To appeal the ruling and obtain a trial by jury, the defendant was required to post a $200 bond, with two sureties, to ensure the payment of any fines and costs. If the amount of the liquor exceeded five gallons, the defendant who lost at trial would be punished by a fine of $100 or imprisoned for sixty days for nonpayment.

In Greene, a citizen of New York brought an action in federal court to recover liquor seized from him under the Rhode Island law, claiming that the statute violated the state constitution. Justice Curtis, along with U.S. District Judge John Pitman, found for the plaintiff. The liquor law, they held, violated several guarantees the state constitution provided to criminal defendants, including the right to trial by jury. The provision of the law requiring security for the payment of fines and costs as a condition for having a trial was the most objectionable to Curtis, who wrote:

Natural right requires that no man should be punished for an offence, until he has had a trial, and been proved to be guilty; and a law which should provide for the infliction of punishment, upon a mere accusation, without any trial, if the accused should fail to furnish two sureties to pay the penalty which might, after the trial, be adjudged against him, would be viewed, by all just minds, as tyrannical; for it would treat the innocent, who are unable to furnish the required security, as if they were guilty, and would punish them, while still presumed innocent, for their poverty, or want of friends.

Imposing a condition on the ability of the accused to obtain a jury trial, in Curtis’s view, effectively denied the right to such a trial. If the legislature were allowed to impose one condition, he reasoned, it could impose other conditions as well, “until the right becomes so difficult of attainment, that it ceases to be a common right, and can be enjoyed only by a few.”

Curtis also pointed out that the Rhode Island legislature had provided a criminal penalty merely for seeking an appeal. If the defendant lost the appeal, the fine was increased from $20 to $100, and the penalty for nonpayment increased from thirty days in prison to sixty. “Certainly it cannot be said that the offence is aggravated, by the accused having claimed a trial by jury,” he commented. “If the offence remains the same … must not these additional penalties be founded on the exercise of that right?” If the legislature could attach penalties to the exercise of a right, Curtis added, that right could not be said to be secured by the state constitution.

Finally, Curtis pointed out that the law, by not requiring that the initial complaint charge any particular person with a crime, violated the state constitution’s mandate that the accused was “to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation.” By accusing no one, the complaint withheld due process of law. For these and other reasons, Curtis and Pitman declared the Rhode Island law to be in violation of the state constitution and held that the proceedings under it had not operated to divest the claimant of his property.