You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

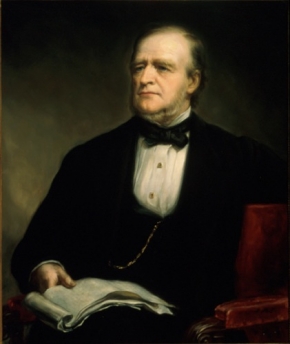

Associate Justice Samuel M. Blatchford, Collins Co. v. Oliver Ames & Sons Corp. (1882)

Collins Co. v. Oliver Ames & Sons Corp., 18 F. 561 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1882) [Second Circuit]

Congress passed the first federal statute regulating trademarks in 1870. In 1877, while serving as a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Blatchford heard La Societe Anonyme des Mines v. Baxter, a trademark dispute involving zinc oxide used for the manufacture of paint. The defendants had used the plaintiff’s trademark on their product, zinc oxide ground in oil. The plaintiffs, however, sold zinc oxide only in dry form and not ground in oil. Blatchford ruled that because the parties sold two different products, the plaintiff’s trademark had not been infringed. By way of analogy, Blatchford explained, a baker falsely stamping his bread with the trademark of a flour manufacturer would not be guilty of trademark infringement either. Such would be the case with any raw ingredient used in a manufactured product.

Five years later, while riding circuit as a justice of the Supreme Court (having served as a U.S. circuit judge in the interim), Blatchford heard Collins, a case somewhat similar to Baxter. In this case, the plaintiffs and the defendants were both manufacturers of agricultural tools. The defendants, Oliver Ames & Sons Corporation, had for many years been exporting to Australia shovels marked “Collins & Co.” The practice started when a dealer told the defendants he had received a large order from Australia for “Collins’ shovels” at a time when the Collins Company did not manufacture shovels. He asked the defendants to fill the order but to stamp the shovels with the Collins name.

Justice Blatchford, in contrast to his earlier opinion in Baxter, held that the defendants had infringed the plaintiffs’ trademark even before the plaintiffs began to make shovels. The brand “Collins & Co.” had acquired a favorable reputation in Australia for making other high-quality agricultural tools. The defendants’ only intent in using this name, Blatchford concluded, was to appropriate and profit from that reputation. The fact that the defendants manufactured many more shovels than the plaintiffs and began making them earlier did not give them the right to use the plaintiff’s trademark on any product. In 1936, Judge Learned Hand of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit cited Collins as the earliest example of what by then had become a well-settled rule—that a defendant could be held liable for trademark infringement even when selling goods different from a plaintiff’s products.