You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

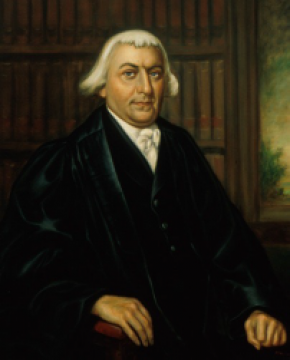

Associate Justice James Iredell, Case of Fries (1799)

Case of Fries, 9 F. Cas. 826 (C.C.D. Pa. 1799) (No. 5,126) [Middle Circuit]

The Case of Fries marked the second time in the space of five years that the federal courts were called upon to decide the fate of citizens accused of insurrection against the United States. In 1799, several years after the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania, another uprising against federal authority took place in the northeastern part of the state. German American farmers in the area were inflamed by a new federal property tax—the first direct tax on U.S. citizens—which required assessors to measure windows in order to estimate a house’s value. The protestors viewed direct taxes as unconstitutional infringements of their liberties and as reminiscent of the British taxes they had fought a war to escape. The tax also favored land speculators over farmers, they alleged, because settlers who had improved their property would pay a higher proportion of their property’s value than would the owners of unimproved land.

One of the leaders of the uprising, John Fries, was accused of threatening assessors with violence if they did not abandon their duties and leave the area. Fries also was alleged to have led a mob that intimidated a U.S. marshal into releasing prisoners who had been arrested for interfering with the enforcement of the law. After the rebellion ended, Justice Iredell gave a long and wide-ranging charge to a federal grand jury, which then indicted Fries for treason. Some critics asserted that Iredell’s charge, in expressing Federalist views, had included overly partisan and inflammatory remarks. After condemning the French Revolution and praising the Alien and Sedition Acts (which were motivated by the government’s fear of conflict with France and strongly opposed by German Americans), he turned to the tax rebellion, defending the fairness of the tax and disparaging resistance to it:

Such incessant calumnies have been poured against the government for supposed breaches of the constitution, that an insurrection has lately begun for a cause where no breach of the constitution is or can be pretended. The grievance is the land tax act, an act which the public exigencies rendered unavoidable, and is framed with particular anxiety to avoid its falling oppressively on the poor, and in effect the greatest part of it must fall on rich people only. Yet arms have been taken to oppose its execution; officers have been insulted; the authority of the law resisted; and the government of the United States treated with the utmost defiance and contempt.

Iredell also presided, along with U.S. District Judge Richard Peters, over Fries’s trial. After a lengthy trial, Fries was convicted of treason. Iredell, however, on hearing evidence of possible bias on the part of one of the jurors, voted to grant Fries a new trial. Judge Peters reluctantly agreed, to avoid casting doubt on Fries’s conviction, although he did not believe a new trial to be necessary. Soon after, Fries was tried again, this time before Justice Samuel Chase and Judge Peters. He was again convicted and sentenced to death. As George Washington had done with the whiskey rebels, however, President John Adams pardoned Fries.