You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

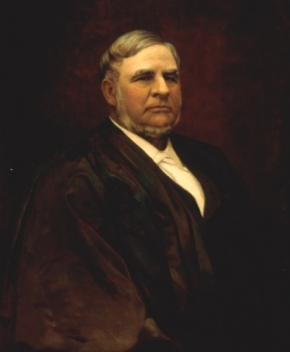

Associate Justice David Davis, Barron v. Illinois Central Railroad Co. (1863)

Barron v. Illinois Central Railroad Co., 2 F. Cas. 934 (C.C.N.D. Ill. 1863) (No. 1,052) [Eighth Circuit], affirmed, 72 U.S. 90 (1866)

William Barron, a former judge in Cook County, Illinois, was traveling from Hyde Park (now a part of the city of Chicago but then an independent suburb) to Chicago on the defendant’s railroad when the conductor noticed an express train approaching rapidly from the rear. The conductor ordered the passengers to leave the car, but while they were in the process of doing so a violent collision occurred, and Barron was killed. The executor of his estate brought a suit for damages under an 1853 Illinois statute permitting personal representatives to bring negligence suits where, if death had not ensued, the injured party would have been entitled to sue. The act provided that any amount recovered would be for the benefit of the widow or next of kin.

The railroad asserted that the plaintiff could not recover because he had made no showing of a pecuniary loss. The decedent’s next of kin, his father and brother, were not financially dependent on him, and thus could not have suffered a pecuniary loss upon his death. Deciding the case on circuit, Justice Davis overruled this defense, holding that the plaintiff was not required to specify that the next of kin had suffered a pecuniary loss.

Davis interpreted the plain language of the statute to mean that an executor could sue on behalf of any decedent who was married or left next of kin. He declined to interpret the second section of the statute—specifying the widow or next of kin as beneficiaries of the action—as containing an implicit requirement of a pecuniary injury. “Many individuals who lose their lives by the fault of persons and corporations are of age, unmarried, and have no next of kin dependent upon them for support. We cannot suppose that the statute intended to give the representatives of such persons the right to sue in one section, and to make that right nugatory in the second section, by depriving all of damages,” he wrote.

In support of his ruling, Davis cited two decisions by New York state courts interpreting an earlier statute similar to that of Illinois and finding that an averment of pecuniary loss was not required. While not binding upon the court, the law of another state could be used as persuasive authority because Illinois’s highest court had not ruled squarely upon the issue. As Davis noted, the Illinois Supreme Court had made statements in a different case implying that an averment of pecuniary loss might be necessary, but that question had not been before the court and was therefore not decided. The Barron case illustrated that part of the justices’ duties while riding circuit was to interpret state law on questions where no clear precedent existed. The Supreme Court affirmed Davis’s decision in 1866.