Historical Context

The period from the 1790s to the 1810s was one of the most intensely partisan phases of American history. The Federalists, who supported George Washington’s administration, believed in a strong national government run by elite members of society. They advocated for closer ties with the British and for Alexander Hamilton’s economic policies aimed at developing a major commercial economy. Republicans, by contrast, were less elitist and had a more expansive view of democracy, as evidenced by their support for the French Revolution. While Federalists saw the nation’s destiny lying in the growth of manufacturing and trade, Republicans favored westward expansion and increased agricultural production.

Partisan conflict came to a head in 1798, when the United States stood on the brink of war with France. In the course of its war with Britain, France had begun in 1796 to seize American ships to disrupt trade with its adversary. After failed negotiations with France to end its interference in American shipping, many Federalists, including President John Adams, believed war was inevitable. Republicans, who admired France’s newly egalitarian society and did not wish to have closer ties with monarchical Britain, fervently opposed going to war. In response to harsh criticism from Republican politicians and newspapers, Adams accused his political opponents of disloyalty. To counter the alleged threat of internal subversion, the Federalists enacted the Sedition Act of 1798, which criminalized virtually any criticism of the government. Several prominent Republicans, including a member of Congress, were convicted under the Act.

The Republicans took power when Thomas Jefferson defeated John Adams in a presidential election dubbed “The Revolution of 1800,” and the Sedition Act expired in 1801. Intense partisan conflict continued until the Federalists faded from the political scene following the War of 1812. Federalist newspapers published frequent attacks on Jefferson and his administration, including the broadside that resulted in the Hudson and Goodwin case. The Republicans, however, having a far more expansive view of the First Amendment than the Federalists had espoused, did not enact any new legislation addressing seditious speech.

Legal Debates before Hudson and Goodwin

The Hudson and Goodwin case addressed the question of whether the federal courts had jurisdiction over common-law crimes, meaning crimes not identified by any federal statute. In the earliest years of the republic, some cases of this nature were heard in federal court. Most of the justices of the Supreme Court—all of whom, until 1804, were Federalists—accepted such jurisdiction as proper when performing their circuit-riding duties. In 1790, for example, Chief Justice John Jay described criminal acts in broad terms when giving a grand jury charge in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of New York, after which the grand jury returned indictments for piracy, a non-statutory crime.

Three years later, in Henfield’s Case, the defendant was tried in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Pennsylvania for serving on a French privateering vessel that was capturing British ships. Although no federal statute imposed a duty of neutrality on American citizens, Justices James Wilson and James Iredell and U.S. District Judge Richard Peters believed that the court had jurisdiction over the case. In his charge to the jury, Wilson explained that the case was governed by “the law of nations,” as well as treaties between the United States and Britain, which pursuant to the Constitution were “the supreme law of the land.” Henfield was acquitted, however.

Justice Samuel Chase was the only one of the Court’s earliest members to express hostility to common-law criminal prosecutions in the federal courts. Although Chase was a Federalist, he had previously been an opponent of the ratification of the Constitution, and he believed strongly in states’ rights. In U.S. v. Worrall, a 1798 prosecution in the U.S. circuit court in Pennsylvania for an attempt to bribe a federal official, prosecutor William Rawle admitted that the case was brought solely under the common law. After Worrall was convicted, his attorney moved to set aside the judgment on the grounds that the court lacked jurisdiction. Chase agreed that the case was not properly heard in federal court because the national government had no common law. “[T]he United States did not bring it with them from England; the constitution did not create it; and no act of Congress has assumed it,” he explained. He nevertheless acquiesced in the mild sentence Judge Peters imposed.

Debates over the Sedition Act of 1798 brought to the forefront the issue of common-law jurisdiction in the federal courts. Uncertainty over common-law jurisdiction was part of the Federalists’ motivation for enacting the statute, but in defending it, they claimed that federal prosecutions for seditious libel were already authorized under the common law. The Act, they asserted, would actually make the law fairer to defendants by allowing the use of truth as a defense. Republicans countered by arguing that common law was entirely a creature of the states, and that for federal courts to exercise common-law jurisdiction would effectively eliminate constitutional restrictions on federal power.

The debate over federal common-law jurisdiction was one part of a larger argument between Federalists and Republicans over the scope of federal judicial power. After being defeated in the elections of 1800 but before leaving office, the Federalist majority enacted the Judiciary Act of 1801, arguably aimed at entrenching Federalist appointees in the courts and expanding judicial authority. The Act created sixteen new circuit judgeships, most of which Adams filled in his final days as President. Perhaps more significant was the Act’s grant to the federal courts of jurisdiction over all cases arising under the Constitution, federal statutes, and treaties, otherwise known as general federal-question jurisdiction. Although the incoming Republican congressional majority repealed the Act in 1802, the Supreme Court decided Marbury v. Madison the following year, establishing judicial review and further inflaming Republican fears of judicial tyranny.

The Case

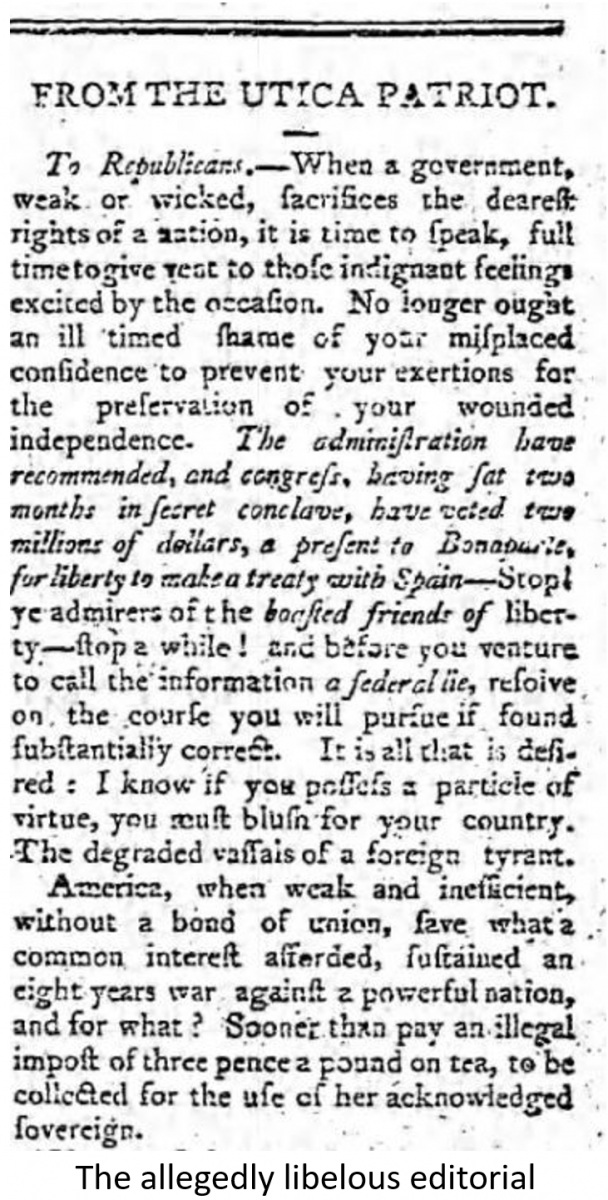

On May 7, 1806, Barzillai Hudson and George Goodwin, Federalists and editors of the Connecticut Courant newspaper, reprinted an article that had appeared in a Utica, New York, newspaper a few days earlier. According to the article, President Thomas Jefferson had convinced Congress in secret to appropriate two million dollars to be paid to French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte. The object of the alleged payment was to obtain the aid of France in convincing Spain to sell Florida to the United States. The article recalled the sacrifices of those who had fought in the Revolutionary War, asking rhetorically if they had been made so “[t]hat your chosen rulers should become tax-gatherers of an insatiable, savage, blood thirsty tyrant[.]”

A few months earlier, Jefferson had appointed Pierpont Edwards to be the judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Connecticut. As district judge, Edwards also presided over the U.S. circuit court for the district along with a justice of the Supreme Court riding circuit. A Jefferson loyalist, Judge Edwards presided over a grand jury, which returned indictments against Hudson and Goodwin for seditious libel in September 1806. Because the Sedition Act of 1798 had expired in 1801, there was no statutory basis for the charge, so it was based only on common law. In Judge Edwards’s charge to a previous grand jury, he had described publications meriting criminal punishment as those “unfounded in truth, or principle, [and] calculated to create distrust and jealousy, to excite hatred against the government, and those who are intrusted with the management of it, and to bring any or all of them into contempt.”

The editors’ trial was originally set for April 1807, but was postponed several times, in part because Judge Edwards had agreed to wait until a new circuit justice had arrived (William Paterson, the justice allotted to the Second Circuit, died in September 1806). Paterson’s successor, Henry Brockholst Livingston, was appointed to the Supreme Court in November 1806, but was not assigned to the Second Circuit until March 1808. When Livingston finally arrived at the circuit court in Connecticut in the fall, he and Edwards disagreed as to whether the court had jurisdiction over a criminal case based on common law rather than statute. As a result, they certified the question of the circuit court’s jurisdiction to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling

Although the Supreme Court received the case in 1809, various delays prevented a resolution of the matter until 1812. Between the 1806 indictments of Hudson and Goodwin and the 1812 Supreme Court ruling, the composition of the Court had changed from a majority of justices appointed by Presidents Washington and Adams to a majority appointed by Presidents Jefferson and Madison. The switch to a Republican-appointed majority might help to explain the Court’s ruling in Hudson and Goodwin.

In a short opinion that cited no precedent, Justice William Johnson, a Jefferson appointee, framed the question as “whether the Circuit Courts of the United States can exercise a common law jurisdiction in criminal cases.” Although the case at hand involved seditious libel, Johnson asserted that the same principles would apply to any other case involving a crime not defined by statute. Acknowledging that the Supreme Court had never before addressed the question presented, Johnson asserted that it was “long since settled in public opinion. . . . in favor of the negative of the proposition.” His claim was perhaps corroborated by the fact that both Attorney General William Pinkney and defense attorney Samuel Dana declined to present oral arguments to the justices.

Johnson referred to principles of federalism in explaining his conclusion that the federal courts lacked jurisdiction over common-law crimes. “The powers of the general Government,” he wrote, “are made up of concessions from the several states—whatever is not expressly given to the former, the latter expressly reserve.” The lower federal courts, which did not derive their jurisdiction directly from the Constitution, had no powers other than those granted to them by Congress. In conferring jurisdiction on the courts, Congress was limited to exercising those powers that had been conceded to the federal government by the states. “The legislative authority of the Union must first make an act a crime, affix a punishment to it, and declare the Court that shall have jurisdiction of the offence,” Johnson concluded.

Although Johnson described his opinion as being that “of the majority of the Court,” none of the justices wrote a dissenting opinion, and the votes were not recorded. Scholars have expressed the belief that Chief Justice John Marshall and Associate Justices Joseph Story and Bushrod Washington—all strong nationalists—most likely dissented from a ruling sharply limiting the power of the federal courts. The lack of dissenting opinions, according to one scholar, was probably the product of Marshall’s preference to have only a single opinion in each case in order to build the institutional strength of the Court.

Aftermath and Legacy

Justice Story vehemently disagreed with the result in Hudson and Goodwin, and tried to rectify it a year later when he heard U.S. v. Coolidge in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Massachusetts. In that case, Story held the federal court to have jurisdiction over the illegal seizure of a ship on the high seas despite the lack of a federal statute encompassing the crime. Despite Story’s attempt to distinguish Hudson on the basis that the federal courts had exclusive jurisdiction over admiralty cases, the Supreme Court reversed his decision and reaffirmed the validity of the Hudson ruling.

Although Hudson and Goodwin remained valid law, it eventually became less influential, as the nationalist view expressed by its opponents prevailed and nearly all crimes became cognizable in federal court. After the Civil War, Congress began to expand federal criminal jurisdiction significantly, enacting laws for the first time that covered conduct already criminalized under state law. The trend toward federalization of criminal law accelerated in the twentieth century, particularly following the dual federal-state enforcement scheme of Prohibition. By the end of the twentieth century, approximately 40% of the federal criminal statutes enacted since the Civil War had been enacted after 1970. In the last few decades, scholars, activists, judges, lawyers, and elected officials have frequently debated whether the federalization of criminal law has exceeded constitutional guidelines, caused unfairness to criminal defendants, or placed an undue burden on the federal judiciary.

Discussion Questions

- What role should the federal government play in criminal law enforcement? Should the states have a more significant role than the federal government?

- Does it make sense for courts to enforce criminal laws that are not in any statutory code? Would your answer be different in 1812 than it would be today? Why or why not?

- What were the positions of the Federalists and the Republicans on federal enforcement of common-law crimes? What explains their differing views?

- Was the law of “seditious libel” consistent with the First Amendment? Why or why not?