Historical Context

The Pullman case was rooted in concerns about judicial federalism—concerns which were first addressed at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. As part of the complicated task of determining the appropriate balance of power between the new national government and the states, delegates debated the plan for the federal judiciary to be laid out in Article III of the Constitution. Many of the framers wanted to establish a nationwide system of lower federal courts in order to enforce federal law. Others feared that such a system would strip the state courts of their significance and undermine the states as independent political units.

The “Madisonian Compromise” embodied in Article III left to Congress the decision of whether and how to create lower federal courts. When Congress did so in the Judiciary Act of 1789, it struck a balance aimed at limiting the federal judiciary’s encroachment upon the principles of federalism. The U.S. circuit and district courts were not vested with jurisdiction over all cases arising under the Constitution and federal law, otherwise known as general federal-question jurisdiction, leaving most issues of federal law to be resolved in the courts of the states.

Other than for a brief period from 1801 to 1802, this compromise persisted, with the federal courts hearing mainly cases pursuant to diversity of citizenship or a specific grant of jurisdiction by Congress. It was not until 1875 that Congress granted the federal courts general federal-question jurisdiction. The subsequent increase in federal-question cases meant that federal judges would be hearing many more state law claims as well when those claims arose from the same set of facts as a federal law claim.

Pullman was such a case—a suit against state officials in which the plaintiffs asserted both constitutional and state law claims. Cases like this raised significant federalism concerns, as federal courts were called upon to determine whether state officials had violated the laws of their own state.

Legal Debates before Pullman

Although the Eleventh Amendment immunized states from being sued in federal court, Supreme Court case law established that suits against state officials could be brought under certain circumstances. In Ex parte Young (1908), the Court upheld a federal court injunction against a state attorney general who had attempted to enforce an allegedly unconstitutional statute. A year later, in Siler v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., the Court ruled that once its jurisdiction had been established by a federal constitutional claim, a federal court could decide the case based solely on a related state law claim. In fact, resolving a case on state law grounds whenever possible was preferable in light of the Court’s practice of avoiding unnecessary constitutional rulings. When the Pullman case came before the Supreme Court, therefore, it was recognized that federal courts could hear suits to prevent state officials from enforcing certain laws, hear related state law claims at the same time, and, when possible, resolve the case solely on state law grounds. Pullman posed a new question: whether federal courts should, under certain circumstances, voluntarily abstain from deciding those state law claims. The case caused the Court to consider the interaction between two established principles: avoiding constitutional rulings when possible, and respect for state courts’ interpretations of state law.

The Case

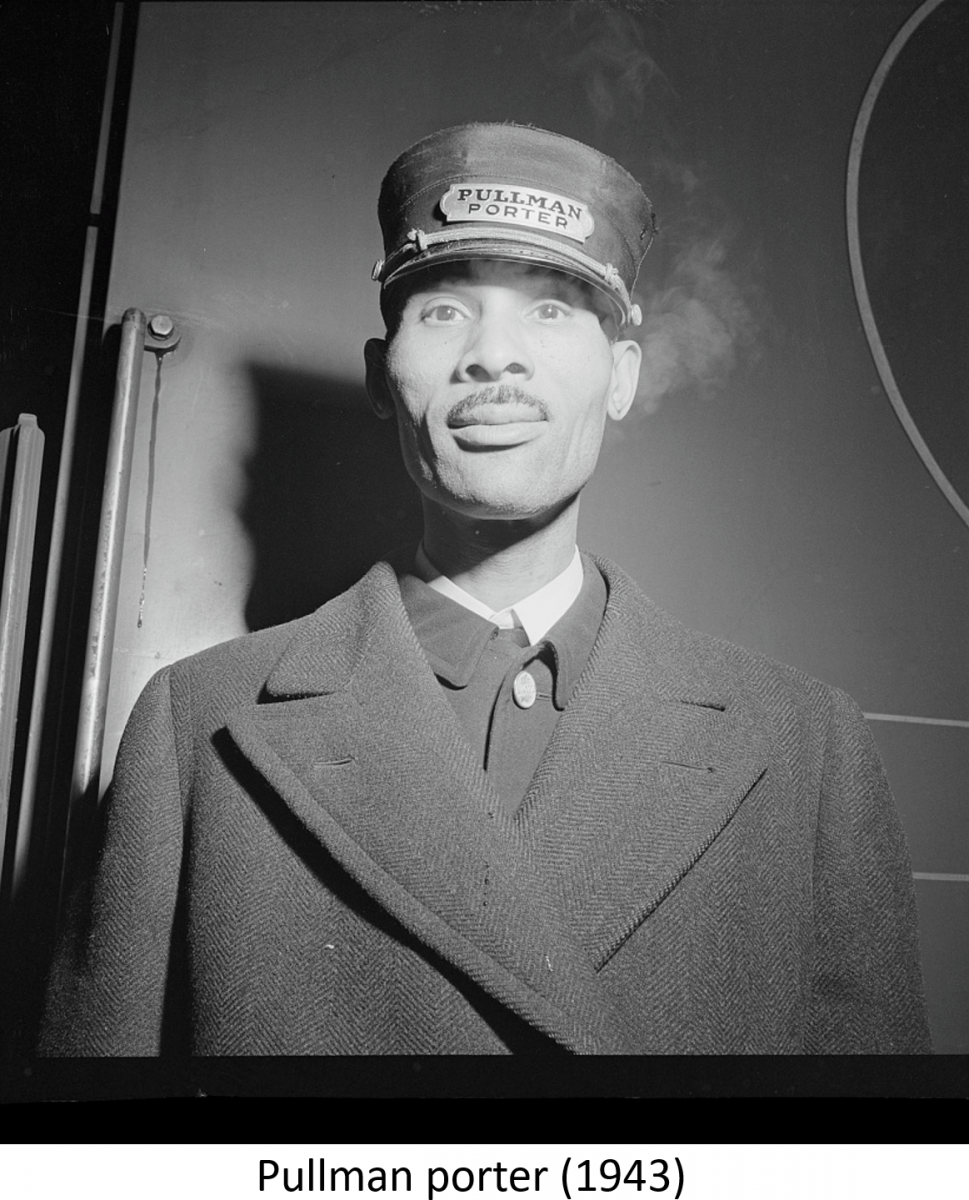

From the 1860s until it went out of business in the late 1960s, the Pullman Company had a virtual monopoly on the manufacture of railroad sleeping cars. The company also employed thousands of conductors and porters to serve sleeping-car passengers. For most of this time, conductors, occupying a higher status position, were exclusively white, while porters were always African American (the first Pullman porters had been formerly enslaved people).

While most trains had two or more Pullman cars, trains in some less-populous parts of Texas, where there were fewer rail passengers, ran with only one. Pullman did not assign a conductor in these instances, leaving a porter in charge of the car. In response to this practice, the Texas Railroad Commission issued a regulation stating that no sleeping car without a Pullman conductor could be operated on any railroad within the state. The commission believed it had the authority to issue the regulation under a Texas statute empowering it to “prevent unjust discrimination . . . and to prevent any and all other abuses.”

Both the Pullman Company and the railroads affected by the commission’s order brought suit in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas seeking an injunction against its enforcement. The Pullman porters and conductors also joined the lawsuit in opposition to and support of the order, respectively. The plaintiffs claimed that the commission’s order was not authorized by Texas law and that it violated the Equal Protection, Due Process, and Commerce Clauses of the Constitution.

The case was heard by a three-judge panel of the district court pursuant to a 1910 federal statute governing suits to enjoin the enforcement of state laws. The panel issued an injunction against enforcement of the order, and the commission appealed directly to the Supreme Court of the United States as provided for by statute in three-judge panel cases.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling

The Supreme Court voted 8–0 (with Justice Owen Roberts not participating in the case) to remand the case to the U.S. district court with instructions not to take further action until the parties could seek a resolution of the issue in the Texas state courts. In his opinion for the Court, Justice Felix Frankfurter noted that the complaint of the porters that the commission’s order was racially discriminatory in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment raised a substantial constitutional issue. The federal courts should not decide the case on constitutional grounds, he wrote, unless there were no other way to resolve the matter. A finding that the commission had exceeded its authority under Texas law would end the case. State law, therefore, should be the starting point of the Court’s analysis.

In looking at the relevant state law, the Court found it “far from clear” whether the order regarding Pullman cars was within the scope of the Texas statute setting forth the authority of the commission. “Reading the Texas statutes and the Texas decisions as outsiders without special competence in Texas law,” Frankfurter wrote, “we would have little confidence in our independent judgment regarding the application of that law to the present situation.” Although the judges of the U.S. district court were more familiar with Texas law than were the justices of the Supreme Court, the final determination of the state statute’s meaning would lie with the Supreme Court of Texas. It would be a mistake, in Frankfurter’s view, for the Supreme Court of the United States to issue an opinion which might soon be contradicted by the state court.

Frankfurter concluded by asserting that the Court should abide by “a doctrine of abstention appropriate to our federal system whereby the federal courts, ‘exercising a wise discretion,’ restrain their authority because of ‘scrupulous regard for the rightful independence of the state governments’ and for the smooth working of the federal judiciary.” As a result, the Court ruled, the matter should be brought before the Texas courts to determine whether their interpretation of state law would resolve the case.

Aftermath and Legacy

The doctrine of “Pullman abstention” was grounded in judicial federalism, as it acknowledged the state courts to be most capable of resolving previously unsettled questions of state law. Proponents of abstention believed that deciding murky issues of state law in determining the legal duties of state officials would have especially serious implications for federalism. In cases where state law was clear, federal courts could still resolve claims on those grounds, whether or not a decision on the accompanying federal constitutional claim was warranted. The most significant objection to abstention was the delay it imposed upon litigants whose claims the federal courts declined to resolve. Although those litigants had the option to return to federal court to litigate their federal claims, the delay imposed could make the federal forum practically inaccessible.

The discretionary aspect of Pullman abstention was significantly curtailed by the Supreme Court in Pennhurst State School & Hospital v. Halderman (1984) (Pennhurst II). In that case, the Court ruled that the Eleventh Amendment barred federal courts from issuing injunctions against state officials based on state law. “[I]t is difficult to think of a greater intrusion on state sovereignty,” wrote Justice Lewis Powell in Pennhurst II, “than when a federal court instructs state officials on how to conform their conduct to state law. Such a result conflicts directly with the principles of federalism that underlie the Eleventh Amendment.” Whereas under Pullman, federal courts had flexibility in deciding whether state law was clear enough to justify issuing an injunction against state officials, the courts lacked the necessary jurisdiction to do so after Pennhurst II.

There were some cases to which Pullman abstention could still be applied, however. Federal courts could decline to rule on constitutional claims against state officials when doing so would require the interpretation of a state law that was intertwined with the federal claim. Also, federal courts could abstain from deciding issues of state law in cases against local officials.

In the decades after Pullman was decided, the Supreme Court developed several additional abstention doctrines, most of which were based on principles of judicial federalism. In Younger v. Harris (1971), for example, the Court held that federal courts should not enjoin criminal proceedings in state courts absent extraordinary circumstances.

Discussion Questions

- Why might it be problematic for a federal court to decide a state law claim against a state official? Did Pullman provide an adequate solution?

- Should state officials be subject to suit in federal court at all? Why or why not?

- Why do you think the Supreme Court avoids making constitutional rulings when narrower grounds for deciding a case are available?