You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

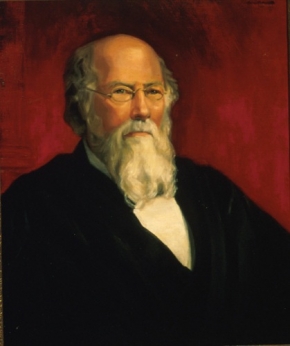

Associate Justice Stephen Johnson Field, In re Terry (1888)

In re Terry, 36 F. 419 (C.C.N.D. Cal. 1888) [Ninth Circuit], habeas corpus denied, 128 U.S. 289 (1888)

The story of Justice Field’s acrimonious and violent dealings with David S. Terry, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court of California (1857–1859), began with two other people—former U.S. senator William Sharon of Nevada and Sarah Althea Hill, with whom Sharon was in a romantic relationship. When their relationship ended, Hill sued Sharon for divorce in an attempt to acquire a portion of his vast silver-mining fortune. Sharon claimed that he and Hill had never been married and that the marriage contract she produced as evidence was a forgery.

Sharon brought a suit in equity in the U.S. Circuit Court for the Northern District of California, seeking a decree that the marriage contract was invalid. He won his suit, and the court ordered Hill to deliver the contract to the clerk of court so that it could be marked “cancelled.” Hill never delivered the document. When Sharon died in 1885, his executor, Frederick Sharon, brought another suit against Hill seeking to revive and enforce the decree from the earlier case to prevent Hill from seeking to enforce the fraudulent contract against Sharon’s estate.

By the time the second suit was filed, Hill had married David Terry (a man with a violent history, having killed U.S. Senator David Broderick in a duel in 1859), so the suit was styled Sharon v. Terry. Hearing the case on circuit alongside Judges Lorenzo Sawyer of the Ninth Circuit and George Sabin of the District of Nevada (sitting by designation), Justice Field found in favor of the plaintiff. His opinion ordered that the decree from the original suit be revived and enforced. Sarah Terry and her husband (who had been added to the suit as a defendant) appealed to the Supreme Court, which affirmed the ruling.

While Field was reading his opinion in Sharon v. Terry from the bench, Sarah Terry stood up and asked him whether he was going to rule against her. After Field ordered her to be seated, she accused him of having been bribed and, as Field later noted, used language “of an exceedingly vituperative and insulting character.” Field then ordered the U.S. marshal to remove Sarah from the courtroom. Before the marshal reached her, David Terry stood up, shouted that no man would touch his wife, “and dealt the marshal a violent blow in his face.” He then attempted to draw a knife but was seized by others present and prevented from doing so. During the fray, Sarah attempted to pull a six-shot revolver out of a satchel she carried but was unsuccessful. After David was led out of the courtroom, he tried to draw his knife again. Deputy U.S. Marshal David Neagle was able to wrest it away from him after a struggle.

Sarah and David Terry were both found guilty of contempt of court and were sentenced to thirty days and six months in prison, respectively. David’s appeal to the circuit court to revoke the order committing him to prison, In re Terry, was heard by the same three judges, with Field again presiding. The court denied David’s appeal, with Field issuing the opinion. Field and his colleagues read David’s petition, which attempted to explain his actions, “with great surprise.” Field wrote that the petition was replete with “omissions and misstatements” and did not “accord with the facts as we saw them” or as other witnesses observed. “Therefore,” Field concluded, “considering the enormity of the offenses committed, and the position the petitioner once held in this state, which aggravates them to a degree not imputable to the generality of offenders, the court, with a proper regard to its own dignity, the majesty of the law, and the necessity of impressing upon all men that forceable resistance to the lawful orders of the courts of the United States will not go unpunished, however high the offending parties, cannot grant the prayer of the petitioner.” David sought a writ of habeas corpus from the Supreme Court, which denied it.

Approximately a year later, Field was on a train with Deputy Marshal Neagle, who was assigned to protect him after the Terrys made several threats on his life. When the train stopped, they sat down in the station’s dining room for breakfast. Soon after, Sarah and David Terry entered the room, unseen by Field. Sarah immediately rushed out (to retrieve her revolver from the train, it turned out), but David took a seat at a table behind Field’s. David then approached Field from behind and struck him on one side of the face and then the other. As he prepared to strike Field again, Neagle drew his revolver and identified himself as a law enforcement officer. Neagle then believed, incorrectly, that David was attempting to draw his knife. He shot David twice, killing him.

Neagle was arrested by the sheriff of San Joaquin County, California, and immediately sought a writ of habeas corpus from the U.S. Circuit Court for the Northern District of California. Judges Sawyer and Sabin heard the case and granted the writ, releasing Neagle from custody. The state took an appeal to the Supreme Court, which affirmed, finding that Neagle had acted in the course of his official duties protecting Field and had not committed a crime. Field did not participate in the case. In 1892, Sarah Terry was declared insane and committed to an asylum, where she spent the remainder of her life.