You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

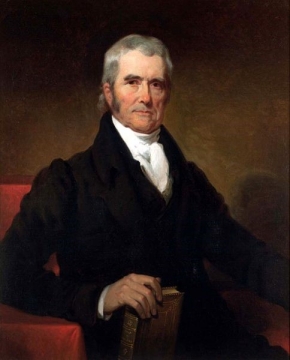

Chief Justice John Marshall, Livingston v. Jefferson (1811)

Livingston v. Jefferson, 15 F. Cas. 660 (C.C.D. Va. 1811) (No. 8,411) [Fifth Circuit]

Attorney Edward Livingston was a former U.S. representative from New York who moved to the Territory of Orleans, soon to become the state of Louisiana (Livingston later represented Louisiana in both houses of Congress). Livingston brought suit in the territorial district court asserting his client’s ownership of land on the bank of the Mississippi River against claims that the land was public. After winning the suit on behalf of his client, Livingston acquired some of the land and began to make improvements on it. Outraged local citizens intervened, blocking Livingston’s workers from the land by threats of force. Fearing violence, the territorial governor wrote to President Thomas Jefferson, asking him to assert federal ownership of the land. Jefferson responded by having Secretary of State James Madison order the local U.S. marshal to seize the land and eject Livingston.

In 1810, Livingston sued Jefferson, who was no longer president, in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Virginia. Jefferson, who did not seek to invoke sovereign immunity in his defense, was convinced that Chief Justice John Marshall, whom he considered a political enemy, would rule against him. Nevertheless, Marshall and U.S. District Judge John Tyler (the father of the future president) ruled in Jefferson’s favor. Both Marshall and Tyler believed that the local action rule—an English doctrine holding that a real property action must be brought where the land is located—should be applied to the case. Under this rule, Livingston would be able to bring his action only in Orleans Territory. Under a different rule prevailing at the time, however, the court could exercise personal jurisdiction only over someone who could be found within the geographical boundaries of the court’s jurisdiction, which meant that Livingston could sue Jefferson only in Virginia. The simultaneous operation of both rules left Livingston without a forum for his claim. He was later able to reclaim his land, however, by suing the U.S. marshal in the territorial court.

The local action rule has remained a part of federal jurisprudence but no longer necessarily presents the dilemma Livingston faced because of more liberal personal jurisdiction standards. As a rule of venue rather than of subject-matter jurisdiction, the local action rule can be waived by the parties if the venue where the land is located is inconvenient.